|   |

|   |

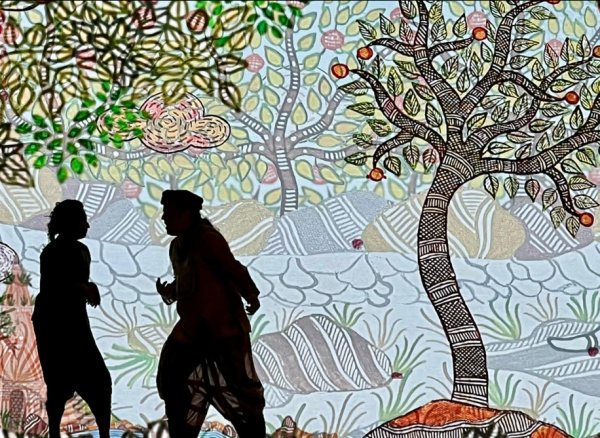

A Jungle Reimagined - Ketu H Katrak - e-mail: khkatrak@uci.edu November 27, 2022 A forest full of roaring, screeching, soft footfalls of large and small animals evoked by a powerful soundscape, with dancer-actors playing animals in brown, black, striped skin textures animated by striking costumes. The laws of the jungle guide animals' day to day life that is separate from the human world; but, behold, a human infant is discovered by the animals! How will this dilemma be resolved? Will it be possible for human and animal to live together in harmony in the jungle? There is suspicion, distrust, and debate about this question presented in The Jungle Book, Rudyard Revised, a theatrical presentation by Northern California based's EnActe Arts. I saw the show in San Francisco on Nov. 12, 2022 at the beautiful space of the Cowell Theater, part of the Fort Mason Arts Center by the Marina. An unusually clear, crisp day with a spectacular view of the majestic Golden Gate Bridge greeted us as we entered the theater for a matinee at 2pm. When we exited a couple of hours later, we were pondering some profound questions raised by the show: could animals and humans co-exist without violence? Could human cruelty to voiceless animals be transformed? Could animals' own hierarchies that considered monkeys (in the show) to be outsiders and not part of the "Council" be reconsidered? Profound issues facing the world today were raised--identity and belonging, insider, outsiders, refugees, migrants fleeing persecution and poverty.  Rudyard Kipling and the Peacock  The Peacock The human child in this "revised" Kipling story is adopted by a wolf mother and raised as a man-cub though the child must pass tests to belong. A young wolf befriends him as a brother. The first half of the show proceeds in an idealistic vein. Two powerful presences among the actor-dancers were Kaa, the Indian rock python played masterfully by Dr. Anita Ratnam, a seasoned performer who embodies her role effectively, and the actor, Brady Voss, as the colorful peacock. Kaa embodied the python role by slithering in a black shimmering costume, and moving gracefully, carrying the plot forward with clearly articulated speech. The peacock was in conversation with Rudy, namely Rudyard Kipling, the original author of The Jungle Book (1894). Rudy is drawn into discussing how he might have told his story differently, namely, from the animals' points of view. Further, in contemporary postcolonial times, how would the forest have appeared to him rather than in the British colonial world that he inhabited? In presenting a live actor playing Rudyard Kipling the show offered clarity to the audience. However, theatrically, a voice-over might have worked. One could also imagine the peacock, who complained bitterly about being left out of the story by Rudy, thrusting himself into the narrative! What worked well was that this Rudy was tutored, educated, even somewhat transformed from his colonial gaze by the peacock's dialogues with him. The peacock's humor and presence on stage were highly delightful. The show began with a video of The Center for Wildlife Studies' Director Dr. Krithi Karanth whose scientific research in India and Asia spans 23 years encompassing "many issues in the human dimensions of wildlife conservation." Dr. Karanth has made significant contributions with her studies on the "impacts of tourism, land use, species' extinctions and understanding human-wildlife interactions." The audience learnt about the multiplicity of initiatives and activities mounted by this group that aims to create synergy between humans and animals. This Center, active in certain States in India, conducts worthwhile research. The Center shared useful and sobering statistics on video as an apt precursor to the show that created an ambience where human-animal connections could be imagined.  In the first half of the show, as the man-child grows, he is protected, at times, in Kaa's long and beautifully curled, soft scaly embrace actualized with a long scarf wrapped lovingly around the human child. For Ratnam, Kaa "represents Krishna, the ultimate manipulator of stories". This python has many sides including wisdom, intrigue, and an ability to foresee what will befall the animal world when it clashes with humans. Ratnam, a powerful presence on stage, re-imagines Kaa in light of the power of the snake goddess in Indian spiritual life. Kaa asks the child two probing questions: Who are you? What are you? The child is unable to answer but it is clear that he has ONLY known the jungle world so far. He is integrated into the animal world, remaining innocent of human capacity for domination and destruction of animal habitats, lives, and subsistence until a human hunter enters the scene, captures the child and takes him/her away into the village. At Intermission, in a resonant, theatrical voice, Kaa asks what will happen next? What choice will the child make? To stay with humans as an outsider, or return to the jungle endangering other animals who will be hunted by humans searching for the child?  Post-intermission, we see the child trapped inside a jail (shown in a beautiful set design made with colorful ropes), captured by humans. It was after all not the child's fault that he was raised in the jungle and did not know how to interact with humans. Matters of justice and betrayal were felt by animals as embodied in the powerful tiger Sherbaag who had personally experienced human cruelty; his father was killed, and his tiger skin was spread on the floor for humans to trample on. Sherbaag is very clear that humans are dangerous and destructive and that it is best for animals to remain far from them. He wants to eat the child and put an end to any possible human interaction; however, Kaa saves the child. Sherbaag is foiled but not defeated. Nor has he changed his mind. The plot culminates when the child returns to the jungle to claim his place, urging compassion and connection between the two worlds, not allowing the humans to kill the tiger. Further, Mowgli reaches into Sherbaag's angry and embittered heart to change it, by pointing out that they are both similar in being separated from their families and not belonging. The child urges both worlds--animal and human--to live together in peace. "The world is big and we are small, so let us think and be still": this wise line is sung by the entire cast at the end. This could have been an effective ending leaving the audience to ponder this profound message. In the production though, there appear to be several endings with movement, words, dancing and these words interspersed. Being "still" would have made for a powerful conclusion since there is really no resolution to the man/beast, village/jungle dichotomies and enmities. The two remain separate though Mowgli, in his own child-like efforts, tries to advocate harmony. This production had a creative team of 14 writers aged 6 to 66 who spent three months adapting the Kipling story within a context of "Black Lives Matter, MeToo, refugee crises, and tiger extinction concerns, raging wildfires" across many parts of the world (Program Notes). They elected to retell Kipling's story within a rubric of wildlife preservation and linkages between animals and humans. As Founder and Artistic Director of EnActe Arts, and the show's Director, Vinita Sud Belani asks: "What would a jungle village co-existence look like?" Belani's production aims to excavate significant issues of "identity, belonging, and conservation" by "re-examining" Kipling's book "through the modern lens of universal belonging, wildlife conservation and sustainability."  The production included a talented team--Associate Director, Noah Luce; music composer and saxophonist George Brooks; choreographers Dr. Aparna Sindhoor and Anil Natyaveda; costume designers Oona Natesan and Sandhya Raman; makeup and hair stylists, Jeshka Yurash and Caitlyn Slavich; set designers Keya Chatterjee along with Madhubani artist Avinash Karn. The Program Notes state that Avinash Karn has taken Madhubani painting, the folk art of the Indian state of Bihar, "once the domain of upper-caste artists to young girls from underprivileged areas of society, encouraging them to use the art to express and incorporate the effects of social ills like communalism, alcoholism, unemployment, gender inequality and lack of girls' education in their lives." This show opened in Palo Alto, California, then continued its run in San Francisco, Nov. 11-13, and 18-20, and presentations at San Jose's Hammer Theater on December 2-4, and 9-11. A large cast of characters, 15 in the jungle and 6 villagers made for a lively and enjoyable production. The themes were inspiring for theater goers, school children, community activists and conservationists. The show was remarkable for its many collaborations with actors, dancers, set and costume designers, and for evoking so many meaningful themes that resonate in our contemporary lives. Ketu H. Katrak is Emerita Professor, University of California, Irvine. |