|   |

|   |

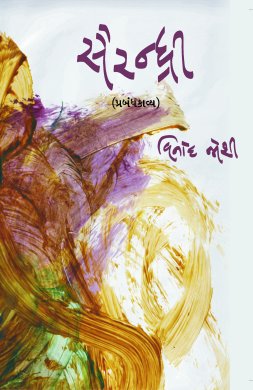

Draupadi gets metamorphosed in Vinod Joshi's verse narrative Sairandhri - Dr. S.D. Desai e-mail: sureshmrudula@gmail.com October 27, 2021 The Prabandh Kavya Sairandhri (seven sections with eight Chopais and two Dohras each) a noted Gujarati poet Vinod Joshi widely known for his lyrics subtly expressing irrepressible young female emotions having folklore kinship has written, engages attention at multiple levels. At the level of literary creation, the long verse narrative, turned into a dance drama, also performed (Parth's direction, Hemal's music for Soor Samvaad and Iksham presentation, Don Moore, Sydney) even with its focal episode and its characters from the Mahabharata, it makes departures from the epic and so interprets its central character Draupadi that she seems to represent the modern uninhibited enlightened woman.

Vinod Joshi As Sairandhri (Bijal), she convincingly keeps looking back to her past depicted in the epic, and in the new contexts the poet has created, as an eminent instance of a strong, sensitive individual denied free will. A major liberty taken with the original has Dhristadyumna on seeing Karna (Hardik) declare at the Swayamvara that his sister will not choose as husband a person skilled in archery but not known to be highborn. Another such liberty the poet has taken is that Draupadi rues the loss and allows Karna's memory to haunt her like a fragrance. At a loss to understand why destiny has her lose her identity as a woman, a person, at crucial stages in life - as an eligible daughter without swayam (herself) having the freedom to choose her vara (groom) , being played as a stake at the dyuta, being considered an object to be shared as a wife, having to stay incognito as a royal maid in agyatvas, having to ward off a lustful arrogant man's advances made to her (a third liberty: it is not Bheem who protects her chastity from being violated and punishes the invader.) At the philosophical level, getting to know one's identity has been a human being's unending quest ever since antiquity in the Indian thought leading to pithy Upanishadic answers. Though Sairandhri never asks this primeval question directly, one hears its echoes in lines like "Abandoning identity, one's own self is thrown into oblivion." On being denied by her brother the freedom to garland the first man in life she loved, she mentions the prison cells (kaaravas) a woman has to live confined to as daughter, wife and sister and laments: "Why on earth me, only a woman, not a free being!" It is at the psychological level, however, that Sairandhri's thoughts and action anchor this narrative poem dedicated with the privilege of closeness 'To you, Woman' all through. Karna's rebuff at the swayamvara was there to see for the kings and princes who had assembled desirous of her hand. It was the rebuff that young Draupadi known for her beauty and individuality felt that remained unnoticed by anyone. With the focus skilfully brought on her by the poet and with the injustices meted out to her and their pain remaining unexpressed so far, the poignancy of all that she has suffered and borne silently becomes all the more sharply felt. There are both poetic justice and a psychological justification that come about in Sairandhri. The Mahabharata's Draupadi, alive in the collective consciousness of the masses, has still been nursing the irremediable grievances. With the poetic freedom he enjoys, sustained creative imagination he has been bestowed with and the capability for dhwani built into his diction and imagery, not unaccompanied by restraint and pithiness, the modern poet with a cultivated sensibility delivers Draupadi - so that she becomes a woman in flesh and blood acceptable to the modern mind. This Draupadi, off the distant mythical pedestal, falls prey to human weaknesses as well. She frowns at Bruhannala (Hardik) holding pretty princess Uttara's (Niyati) hand while teaching her dance and deprived of husband's proximity when she is filled with desire, slips into an aberration of liking Keechak's touch momentarily. At the same time, she emerges different when Queen Sudeshna flaunts gross physicality, accentuated with sensuality, and counterpoints Sairandhri's studied inhibitions, longing ('in husband's company but without his union') and search for identity, intellectually. In a dream flashed, she is an abhisarika for Keechak and later she gives herself up to Karna, who overpowers him.  Bruhannala and Uttara An abiding human trait of the metamorphosed Draupadi at the same time is that her subconscious, like anyone else's whose love is destined to have remained unrequited, cherishes the first sight of the exceptionally radiating face and figure of Karna - 'As though the Sun had descended from the sky!' - and her spontaneous desire to garland him when he is poised to win the archery test set at the Swayamvara - 'This is the man I had been waiting for!' When Kunti suggests the object Arjun had brought home as a trophy be shared by all the brothers, her being from within revolts, but remains unheard, 'I'm a woman!' She gives voice to her painful reality later: 'The heart remained with one and she let the body be shared by five.' When Keechak (Jwalant), brother of Queen Sudeshna (Zarmar; also choreographed by her), is set to assault her sexually, it is neither Arjun nor Bheem who comes to her rescue (yet another significant liberty) in Sairandhri. It is Karna, who had won her heart when she was at the threshold of her youth and years of longing. He has for ever been with her in spirit all these years. It is no mere fantasy. Shri Krishna clothing her when she was being disrobed by Duhshasana in Duryodhana's court has all along been accepted by the masses without doubt. It has the basis today of Sigmund Freud's theory of wish fulfillment. It need not escape notice that the word (vag) to a large extent supports arth (meaning) in this long narrative poem, as is evident in the version of the poet's recorded oral recital (ATMA, Ahmedabad) in controlled modulation. Besides, most of the words in it are not polysyllabic (having three+ syllables) and are tatsam in chopai and dohra meters associated with Tulsidas and Kabir's works, both immortal at an elevated level. This lends the 1,764-line text distance, almost an aesthetic distance, from the reader or spectator. Also, the end-rhymes - not all sound spontaneous though - carry forward the even flow of the lines and their depth. For a performance to be at that level, the visual and aural expressions of performers are expected to have the strength of exceptional sensibility and artistic resourcefulness.  Dr. S.D. Desai, a professor of English, has been a Performing Arts Critic for many years. Among the dance journals he has contributed to are Narthaki, Sruti, Nartanam and Attendance. His books have been published by Gujarat Sahitya Academy, Oxford University Press and Rupa. After 30 years with a national English daily, he is now a freelance art writer. |