The Mahabharata: a visual narrative

- Padma Jayaraj

e-mail: padmajayaraj@gmail.com

December 14, 2016

Click on images for enlarged version

Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi organized a 12 day national painting camp

“Mahabharata Vicharam” (30th Oct to 10th Nov 2016) with the Mahabharata

as its theme, at the Akademi Gallery in Thrissur. National level

artists cutting across the country gathered to paint. In the course of

the camp, eminent speakers looked at the Mahabharata from different

perspectives.

The renowned artist Nampoothiri who inaugurated the exhibition spoke of

its national stature and hoped the paintings would be showcased in

different parts of India. Acrylic on a huge canvas, each painting is a

magnificent burst of passion, a visual narrative. The painting

exhibition proved a raconteur of our times. Most of the paintings brood

on, in moody, heavy rhythms, fusing traditions with politics, steeped in

a sense of history.

Bara Bhaskar’s work is commanding: a large painting, acrylic on paper in

shades of earthy brown. The artist indicates the historical

authenticity of the Mahabharata war, painting the excavated site. The

tiny remains, the remnants of their lives take the story of Mahabharata

from a poetic work to the reality of history. Indeed the excavation

proved the theatre of Mahabharat war is the Ganga plains and it did

happen sometime in 10th c B.C.

Tribal issues is an underlying theme of many paintings. Swami

Vivekananda mentions three Krishnas in our ancient times. One was a

tribal chief, for nomadic and pastoral tribes roamed in northern parts

of the sub-continent before Aryan tribes migrated to the plains. K.G.

Babu and Sravan Paswan connect this version with the contemporary

neglect of the tribal by the mainstream society.

Babu K.G is an artist noted for his hyper realism in his work. The

larger than life presentation of the suggested image, the face of a

child, cast in indigo blue with violet tinge is a tribal that recalls

Krishna. Can you imagine a tear-filled Krishna? The sad face, tears

streaking down shows the universal dimension of sorrow. “I will walk to

the depth of deepest forest with you” is the message. The painting is

significant in present day politics that displace the forest dwellers to

confiscate their home, the wilderness.

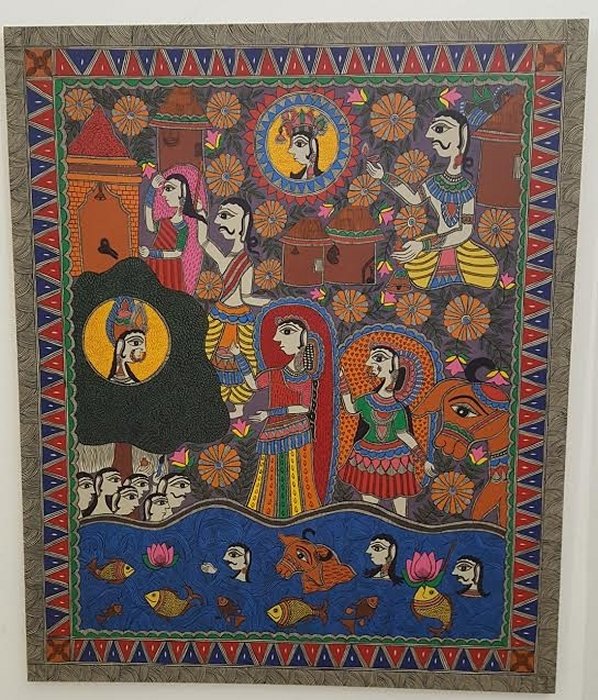

Sravan Paswan, a noted painter of Mithila school in Bihar paints the

plight of his community back home. The upper class sidelines them.

Krishna and Ganga are their only consolation in his narrative.

From Ekalavya to Rohit Vemula, the same story goes on: the crushing of

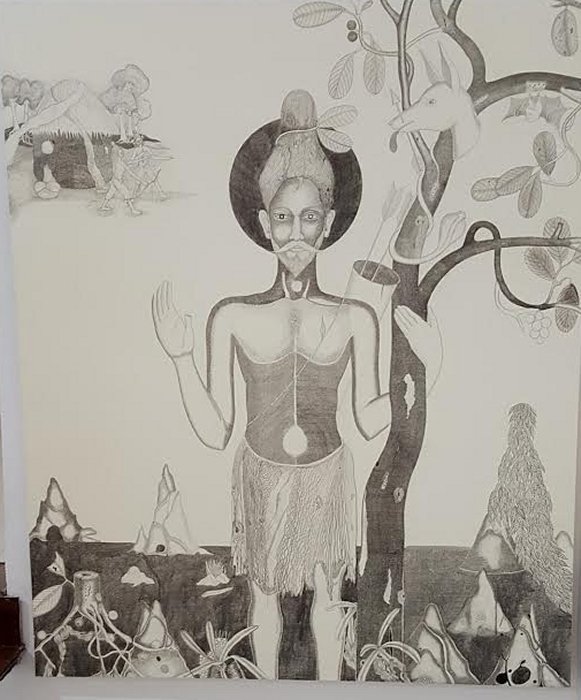

the tribal talent. Pushpakaran thinks drawing has great future. Using

Indian ink as his medium he has painted Ekalavya as the prince of the

wild. On his right is the civilized world that cut his finger and his

home the tree; on his left is the forest in stylized form, home to flora

and fauna.

Sindhu Divakaran connects the iconic youth Ekalavya who haunts our

conscience to Rohit Vemula the promise nipped in the bud in our great

university. The ideal Indian pose gives the painting mythical dimension;

the enveloping brown the gloom of their plight; the radiant white their

talent; the reddish tinge the tragedy.

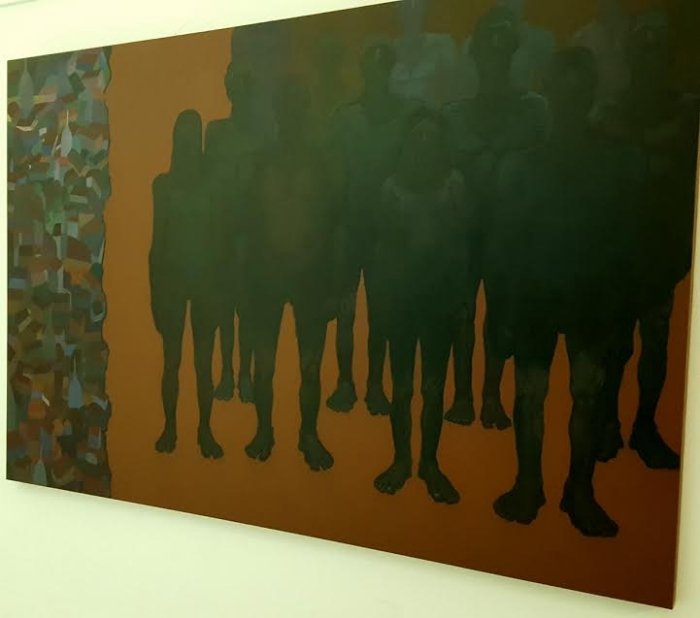

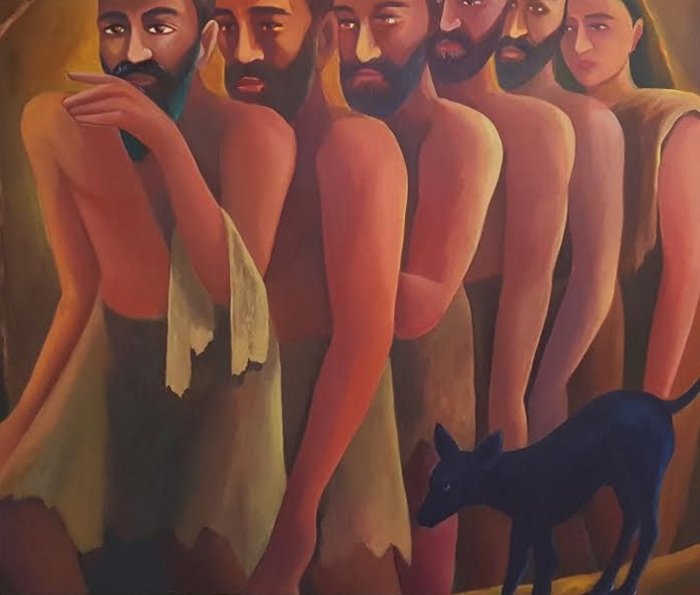

V.S. Madhu brings the tribal to the center in his canvass to remind the

viewer of the native people of the subcontinent. Hidumbi, Gadotgajan,

Ekalavya and their descendants, in an unending line in silhouette, pose

question marks.

For Dinesh P.G, his canvas is a representation of how memories and myths

work to create a painting. The entire canvas, brown in color, is the

picture of a pond from his childhood memories. In the center we find a

linear drawing that is evidently of Bhishma on his bed of arrows. The

waters are now transformed into the waters of Ganga. The nervous system

of his body that matches with his hoary hair stands for the rivers and

rivulets of the land. Though farfetched in theme, the impressionist

style, captivates the attention to the pivotal figure. The magic of

minimalism with contrasting images attract the viewer.

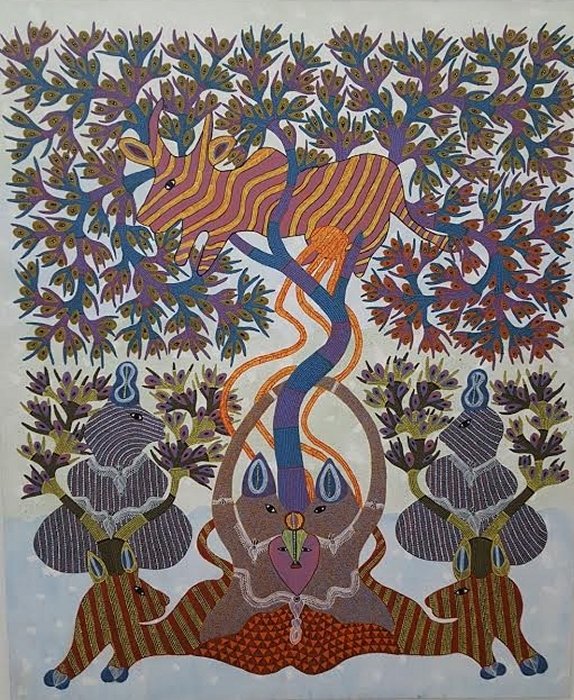

Ramsing Urveti presents another narrative of the Mahabharata, an example

of how the story got embedded in the subcontinent. Here, Siva and

Parvati on either side are placed above a picture that tells

a myth: the story of Pandu’s curse unknown in this part of

India. The images of a pastoral life make the canvas a retelling of the

story of a tribe, perhaps Krishna’s tribe.

Women smothered by patriarchy, is another theme. Perhaps, Gandhari

blind-folding her eyes to be a pathivrita is the root cause of the

Mahabharata war. Kunti’s hapless plight and the story of Karna is a sad

tale in a patriarchal society. The disrobing of Draupadi that shocks the

sensibility is a daily event to date. The gambling board recurs as a

symbol in many paintings to indicate the nature of politics.

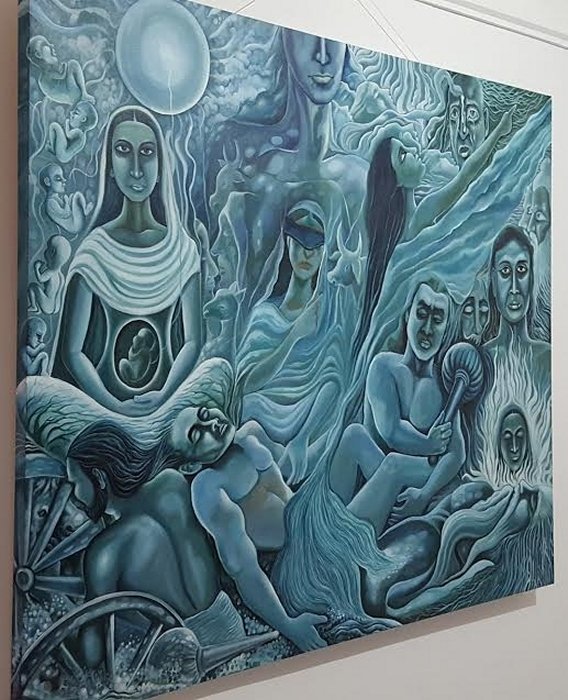

Sreeja Pallam depicts the plight of the women in the story, a repetition

in our own times. Her canvas projects life from birth to death, leading

to the peace of acceptance after the tumult - an endless fight against

inimical forces that pushes one to compromise. Kunti, the pregnant

mother with the Sun above her, Karna meeting his death below, is the

tragedy of a girlish whim. The blind-folded Gandhari with her dying son

on her lap recalls The Pieta, the cause and result of her

thoughtless decision. Draupadi with Bheema, her avenger, point to the

war and its aftermath: the eternally wandering Aswathama and Bhishma on a

bed of arrows. Shikandi, the 3rd gender is not spared in this

recap of visuals with contemporary resonance.

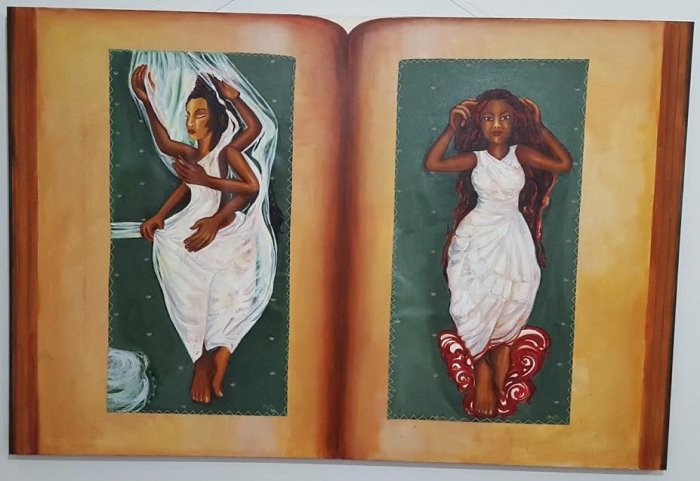

Sreekumari places the game board in the center and on its middle on a

bed of arrows she places a woman, perhaps herself, the pawn. Two

metaphors coalesce here, Dharma and the woman in the game of power

politics. A shower of peacock feathers that trickles down to the dress

of the Indian woman is perhaps the only hope even today.

Smiija Vijayan highlights the tragedy of Kunti and Karna.

Deepti Vasu and Muthu Koya take up one of the contentious issues to

date: rape. Deepti’s painting is figurative depicting the fury of

revenge while Muthu Koya’s work is a powerful portrayal in symbolic

dimension powered by impressionist mode. The losers are mainly women.

Latha N.B in her absract painting portrays the cry of the land rising to

the sky and collapsing in a whimper in an acceptance of the inevitable.

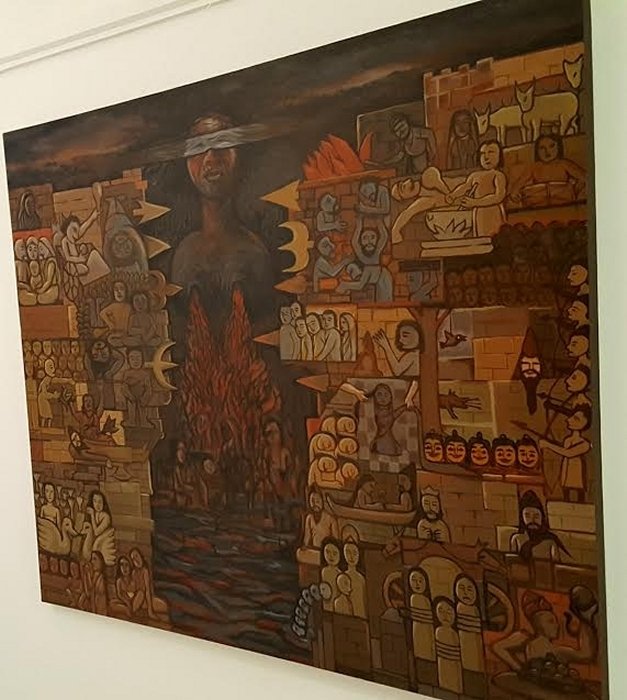

Manoj Brahmamangalam takes the pain of war. The artist has painted

bricks in the background to construct his visual narrative. The color

scheme brown and grey with streaks of red, takes the viewer to the court

premises where war brewed. The visuals gather around the tragedy of

war, Gandhari Vilapam: the mother image, carrying the flames of anger,

pain, loss and death within.

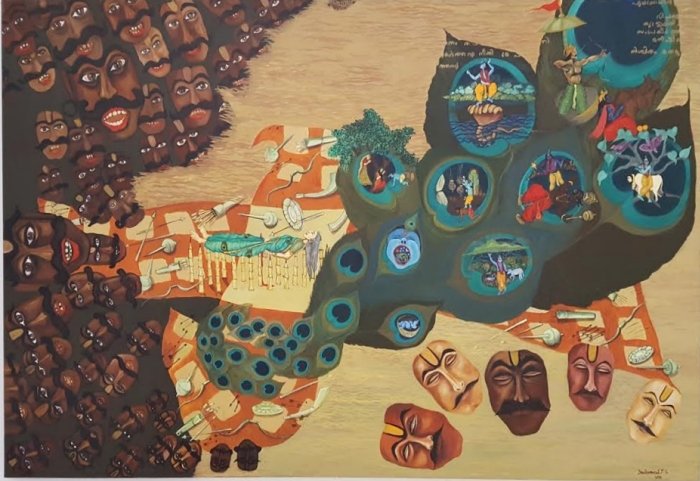

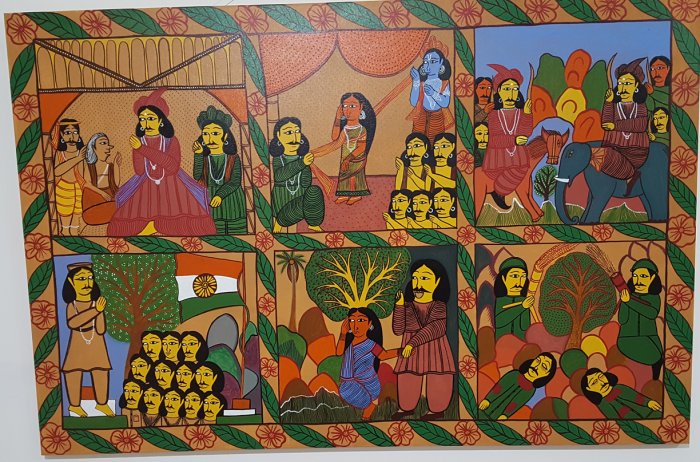

Power politics is the theme in some paintings. Gurupath Chitrakar from

Bihar paints it as two parallel streams in his traditional patachitra

style. Three pictures: coronation of Karna, disrobing of Draupadi, a

scene from war, has a parallel. We see a replica of present day India:

the Minster under the national flag, the plight of the woman, and

Kashmir the troubled spot, symbolic representations of the same theme.

The Mahabharata, yes, ironically, is our tradition. A caustic comment

from a humble artist is quite revealing.

Udaya Kumar fuses the iconic Bhishma and Gandhiji for persecution of

values in politics. Despite the calendar art style, it is a powerful

presentation.

Jalajamol points to the inherent loss in any war. The mirror image of a

man aiming at himself is the tragedy of war, anywhere, anytime, although

the context is when Dharmaputra realizes Karna to be his brother.

K.P. Reji, a Baroda based artist, fuses the story of Duryodana trapped

by Krishna’s advice with the modern uniform of soldiers who fight in

jungles. The background resembles the camouflaged military clothes meant

to ambush the enemy. The traps of war are the same.

Thomas Kurisingal, is concerned with contemporary issues. His painting

in colorful visuals recounts the turning points of Mahabharata, which

symbolically represent the evils of modern society. Pointing to private

loss and public crisis the painting solicits to mediate in human history.

The holocaust of war is the theme of Bahuleyan. In animal imagery, war

fossilized is the canvas of the artist. The gadha in the middle recalls

the earth in the midst of death.

In the painting of Sanil KumarK.K, the images from Picasso’s Guernica

and military tanks sporting flags, in grey, is a commentary on modern

war. The stories of destruction in Mahabharata war bordering the

center in brown color and in line drawings recall old palm leaf

manuscripts.

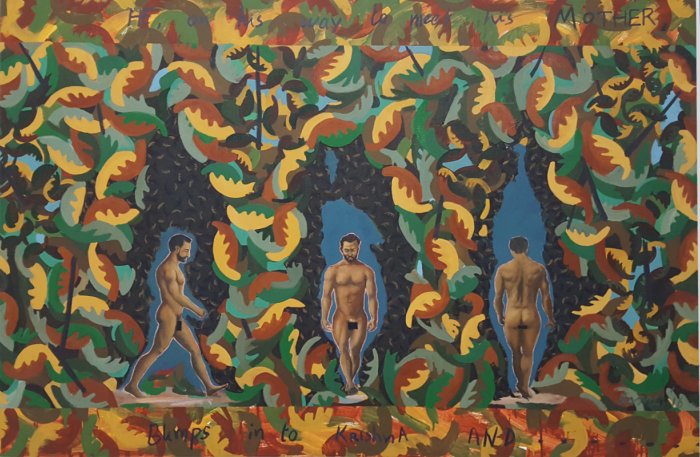

Premji’s canvas, the final journey of the Pandavas dogged by the dog is

the finality of death after a life in search of glory, in a gory

battlefield. The dog stands for the karmic baggage as well as death. The

painting speaks of private loss and public crisis in the context of the

Mahabharata.

G. Pratapan hints at the insignificance of humans and the earth their

home. The painting pricks the ego like a bubble. His work

showcases a telescopic reach to the astronomical span where the earth is

a tiny thing.

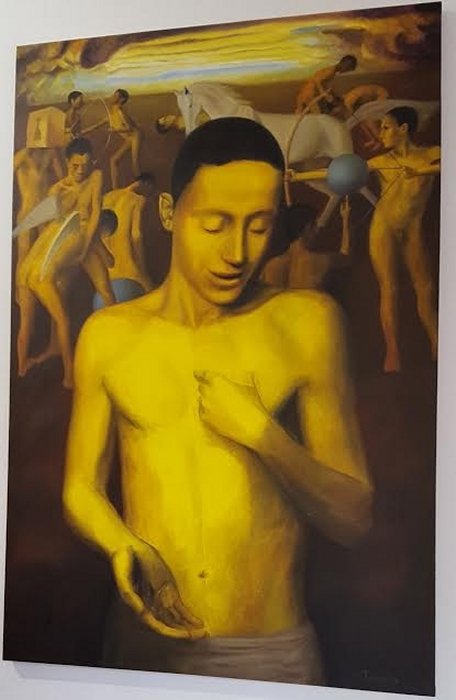

Tom Vattakuzhi presents Shanti mantra, the message of Shanti Parva in

the Mahaharata. The luminous, inward looking, relaxed figure pointing to

the heart is a painting that reminds of Buddhist way of life, the ideal

for which the subcontinent is famous for.

Although each artist conceived and executed his work in his and her

aloneness, the entire show as a visual narrative of the epic, of its

landmark events that recall its contemporary relevance, comes a

surprise.

Padma Jayaraj is a freelance writer on the arts. She is a regular contributor to www.narthaki.com

|