|   |

|   |

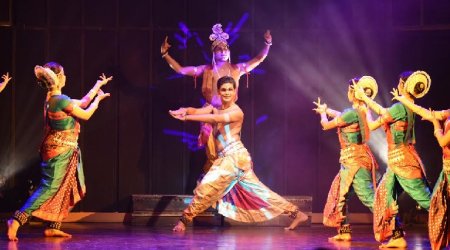

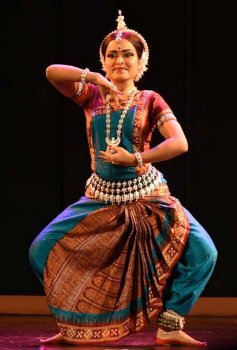

Truly an utsav of dance styles - Shveta Arora e-mail: shwetananoop@gmail.com Pics: Anoop Arora September 20, 2016 Saare Jahan Se Achha is a two-day festival hosted by Utsav, Ranjana Gauhar’s Odissi academy, and it really is an utsav of dance forms from all over India. It was hosted at the IHC in Delhi on 17th and 18th of August. On giving a platform to all these dancers from various disciplines and forms, she said, “It’s a beautiful and fulfilling experience to see our younger generations involved and immersed in classical dance with so much dedication. To create a platform for them at Utsav is like giving back to the society what I received all my life. I feel I am just doing what I should be doing.”  Matsyavatar On day one, the first performance was a group choreography by the disciples of Ranjana Gauhar, titled Matsyavatar. Matsya or meen, the fish, is one of the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu. The matsya preserves the environment and sacred texts from destruction. The performance started with Lord Vishnu depicted with shankha and chakra, and the incarnation as the matsya, enhanced by the lighting patterns on the dancers. Sandeep Dutta always does a commendable job with the lights. Further, as the lord is worshipped as Adinarayana, the story of Brahma writing the Vedas was depicted. He is served by his subjects, who are stringing flowers for him, or making chandan to adorn him. These Vedas are then stolen by the demon Shakasura. The lord takes the matsya form to save the Vedas from the demon. He appears as a small fish to Satyavrat, who is a religious and kind king, and asks to be saved. The little fish was enacted by young Anika Tandon, with grace and aplomb. The fish grows rapidly as the king and people look on. They keep bringing more water to accommodate it, and finally, the matsya appears as the chaturbhuj Narayan, and there is an epiphany that on the seventh day, as the world drowns in a flood, the matsya will be the saviour. The lord fights the demon, and brings back the Vedas safely with the recitation of the shloka, ‘Yada yada hi dharmasya’ and the stuti “Keshava dhrit meena shareera jaya jagadeesha hare.” The dancers posed in the four-armed posture of Lord Vishnu, with the matsya in the foreground. The group’s coordination and rhythm were graceful and enthralling, with a special mention of Vrinda Chadha, Ranjana’s senior disciple. The fighting scenes were in Chhau. The dancers were Dhinabandu Dalai, Aditya Srivastava, Simar Sokhi, Anica Tandon, Kyra Mehra, Vritti Tandon and Vinod Kevin Bachan.  Sarita Kalela Sarita Kalela, a gandabandhan disciple of Kathak Guru Uma Dogra, commenced with a thumri “Na maro Shyam pichkari.” The gopi is pleading with Krishna not to smear her with colour on Holi since her in-laws will talk badly of her. It is in the tradition of Vrindavan Holi, with chhed-chhad (flirtation). Sarita’s abhinaya as the gopi was quite toned down, but with very expressive eyes. This was followed by a tarana in teen taal. The nritta was executed using gat, footwork and chakkars. The technique was good, but the audio for the piece did not have the required volume.  Shubha Dhananjay This was followed by Bharatanatyam by Shubha Dhananjay from Bangalore. The Nataraja padam described the divine dance of the lord in the temple of Chidambaram. Lord Shiva has no aadi or anth, beginning or end. The moon resides on his forehead; he was the one who drank the poison from the amrit manthan. The composition was by Papanasam Sivan in ragam Purvikalyani. Shubha tried to execute the piece with a lot of movement, leg lifts and balancing, but every dancer has a bad day, and she gracefully apologized for her stiffness and balance issues. The next piece was a Subramaniam rhythm, set to raag Bihag in adi talam. The tale says that sparks flew from the third eye of Shiva and settled on the flowers in a pond, turning into six babies. Goddess Parvati collects them all and makes them into one child, albeit with six heads. That’s how Lord Kartikeya was born, known also as the son of Agni. He rides a peacock. In the sanchari, his brother Ganesha, helps him in the Valli kalyanam. Shubha could present the abhinaya for this piece with better balance and gestures.  Maya and Mudra Dhananjay Maya and Mudra Dhananjay, Shubha’s daughters and disciples, presented Kathak. They’ve also been learning Kathak from Guru Geetanjali Lal. Their first piece was an invocation to Lord Shiva in raag Malkauns set to ektaal, a composition of the late Dr. Maya Rao. It describes the attributes of Lord Shiva, the chandra (moon), trishul, trinetra (third eye), pinakdhari, bhasma-bhushit (covered in ash), gangadhar (He who wears the Ganga), damaru (drum), rishabhavahan (He who rides the bull), bhootnath (Lord of the ghosts), wearing a rundamaal (garland of skulls). The attributes were executed with a lot of grace and poise by both the girls. The bandish was a choreography of Guru Geetanjali Lal – “Bijuri chamke barse megha” (lightning strikes, clouds pour). The thunderous sky heralds the monsoon, and the mood for romance. The melodious call of the nightingale is the high point of the season. The swings have been hung from the trees, the peacocks are dancing, the cuckoo sings on the trees, while Radha and Krishna run to meet each other in the nikunj. Again, their grace and exactness of movement were apparent. The tarana was choreographed by Guru Geetanjali Lal in raag Bageshwari, set to teen taal. At times, they fell out of sync, but on the whole, a good performance from very promising dancers, who are learning two diverse forms of dance, Bharatanatyam and Kathak.  Sharodi Saikia & group The next evening started with a Sattriya performance by Sharodi Saikia, a prime disciple of late Guru Raseswar Saikia Barbayan. She performed to a Krishna Vandana composed on the basis of Na-Dhameli with instruments like the khol and cymbals. The first composition salutes Krishna, the son of Devaki and Vasudev, who has feet like lotuses, eyes like lotuses, wears a lotus garland, he who is the killer of demons. The bhaktas seek his compassion and craves for the dust of his lotus feet. The music had the lilting melody of northeast Indian music, with the dancers accompanying Sharodi swirling to the khol and manjira. Accompanying her were Dwijen Burman and Debojit Dutta on cymbals, Banamali Baruah and Sanjeev Kachari on khol. The next piece was a composition by Madhavdev. Krishna steals butter from the gopis’ house, and they come to complain about it to Yashoda, who then punishes Krishna by boxing his ears and reprimanding him. But little Krishna apologises to her and the discord between mother and son is amicably settled. The movements of the dancers were slow and fluid and the abhinaya understated.  Rajashri Praharaj Rajashri Praharaj, disciple of Guru Ratikant Mohapatra and a senior faculty member at Srjan in Bhubaneswar, presented Odissi. She began with an invocation of Lord Ganesha, Vinayak Smarnam. He is worshipped by his devotees fervently. The lord, son of goddess Gauri, is known by his twelve names - ekadant (one-toothed), vakratund (He who has a twisted trunk), krishnapingaksh, gajapateye (the elephant god), lambodar, vikat, vighnarajan, dhumravarna, bhalchandra, vinayaka, ganapati, gajanana. The choreography was by Ratikant Mohapatra and music by Vinod Panda. In “Om Gam Ganapatye Namah,” she depicted the ears, trunk and the mouse as the steed. Rajashri’s gestures, stances and interpretive dance had a completeness and exactitude about it. Her mudras, footwork, chauka, leaps, agility, balance and leg swings, all made the performance a visual treat. The next piece was a pallavi, a nritta piece, an elaboration of music, chemistry of rhythm, dance and movement. It was in an unconventional taal, in 15 beats, called panchamsavari. This is rarely used in Odissi. The composition was in raag Chandrakauns, taal panchamsavari, with the rhythm of 4, 3, 4, 4. The music was by Pradeep K Das, and choreography by Ratikant Mohapatra, a totally riveting and mesmerizing performance. There are a few performances which are so graceful in movement that they leave an imprint on your mind. One such was the performance by Mom Ganguly and Manjula Murthy, disciples of Guru Bharati Shivaji, in Mohiniattam style. The performance began with an ashtapadi, which is performed in the Guruvayur temple as the kottipadiseva. Bharati Shivaji has incorporated the ashtapadi into the repertoire of Mohiniattam. The sakhi is persuading Radha to go and meet Krishna, who is anxiously expecting her on the banks of the river Yamuna. The composition was in raag Kedara Gowla, and Shriraga. The abhinaya by Manjula as the sakhi and Mom as Radha had a great deal of finesse. “Dheera sameere Yamuna teere” – Radha is reminiscing about the previous meeting with Krishna and their love or ratisukhsar, and is awaiting his coming, the depiction done with a lot of subtlety by the two dancers. The sakhi takes her to Krishna forcibly. The interspersed nritta had wonderfully coordinated swaying of the torso and feet movement, with the edakka playing. The next composition was about the seven steps that lead to the altar of the lord. The dance gradually increases in tempo to a crescendo. It signifies the rhythmic ensemble tradition of Kerala in ragam Natakuranji, set to talamalika. Again, the nritta was captivating. According to the two dancers, “The technique for the dance is as soft and gentle as in Mohiniattam, but more elaborate in the neck and torso. It is more profound than the other techniques of Mohiniattam, and more elaborate than the other schools, which have only a few adavus. You find a lot of variety in the movement, since our guru has taken from other dance forms of Kerala, so it becomes more intricate and pronounced. The abhinaya is also more profound. Kerala has a rich dramatic tradition, but our guru has mellowed it down and made it suitable for lasya and gentle movements.”  Mom Ganguly and Manjula Murthy  Artistes of JNMDA The evening concluded with a Manipuri performance by the artists of Jawaharlal Nehru Manipuri Dance Academy. Shveta Arora is a blogger based in Delhi. She writes about cultural events in the capital. |