|   |

|   |

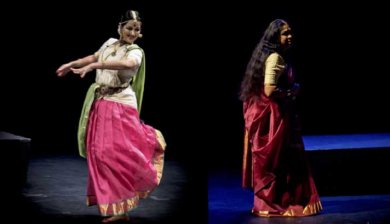

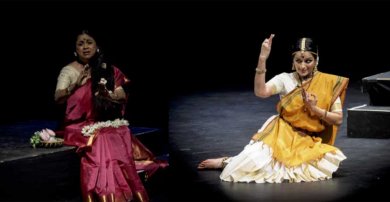

'Aham Sita' by Gowri Ramnarayan and Vidhya Subramanian - Priya Das e-mail: priyafeatures@gmail.com May 7, 2016 On April 2, 2016, Yuva Bharati got us an audience for the women of the Ramayana in Palo Alto, California. Gowri Ramnarayan and Vidhya Subramanian’s Aham Sita - I am Sita- was a side-by-side presentation of thought provoking dramatic narrative by Gowri and evocative Bharatanatyam by Vidhya. The entire prose narrative and the song selection was by Gowri; choreography-in-verse was by Vidhya. It was a joy to watch and welcome Vidhya back to her original home base after many years. Aham Sita took a not-often-seen step, at least in dance theater circles, in raising questions and making questionable some of Ramayana’s characters (pun intended). Seen from the lens of a person-first, it shows Ramayana’s wife-of-the-hero, if not as the heroine, as at least a player with a voice. Urmila gets a voice too, if only to lament that she is the other Janaki, Maithili, and Vaidehi in shadow; Ahalya shares her side of the story; Shurpanakha talks about the elusive joy of revenge, and Mandodari of the futility of being the one that “counts the most.” Gowri and Vidhya are high caliber artists and it was a charged presentation, never a dull moment. Gowri’s spoken words were the bold, staccato outline to Vidhya’s nuanced, colorful, and fine brushstrokes. It was a canvas rich in research, introspection, and evocation. Gowri was powerful, Vidhya was exquisite. But like the Meenakshi in the show, at the end, “Why do we not feel satisfied?” Was it the telling of the story or the aftermath that left a vague unease? One realizes that it was both. As regards the theme, the goal was clearly to get us to pay attention to the sides of characters never heard before. This was met- through prose and verse. That was the expected unease. The unexpected unease was with the purpose of the dancing in Aham Sita- it is undefined. There are two tracks running in parallel: One is Gowri, drawing unusual character studies. The other is Vidhya, performing expressive Bharatanatyam to beautiful, only somewhat related songs. It was a showcase of both talents, but individually. Gowri’s theater, for the most part, raised the hard-hitting questions through hard-hitting personalities. A dancer of Vidhya’s caliber was certainly required to hold her own with Gowri. Otherwise, the movement section of the production would have fallen flat. The song-dances are beautiful, but was that the intent? As the director, did Gowri intend to have dance as eye candy? Or was it an oversight? Subliminally, the dance section showed that life goes on for Sita and other characters, despite the reactions they incite in other people. That would be one way to define its purpose, and it is one way to use Bharatanatyam in the narrative. But the role played (in most parts) by the verse was simply to provide a soothing …what exactly, backdrop? vignette? diversion? That it lags so severely behind in the philosophical quotient is disappointing and more importantly, distracting. The audience cannot grapple life-defining questions and enjoy tenuous connections to poetry alternatively. The point is, if dance is going to occupy so much of stage time, then it must measure up intellectually. Was it a case of not knowing how to use dance? Then why reserve so much time for it? It is a sub-optimal use of the narrative real estate to merely include rather than integrate the song and dance. If the songs are simply too good to be excluded, then make the flow smoother by having the songs lead up to Ahalya and Shurpanakha speech segments, each. One could even conclude that it is too much of a good thing. A sad but corrective measure would be to remove Kahan ke pathik and Ramamani out of the narrative. On the positive side, there was a lot that really worked in the show, an account follows. The opening act was Gowri standing alone on stage. She is an older Sita who is nonplussed by the content of Rama’s letter (which will not be revealed here). Gowri managed to, in a few minutes, force us to look at Sita devoid of the gilded lens, kudos.  Exit older Sita, Enter Sita: Vidhya then enters the stage unmistakably as a teen Sita in Ennaarunalathinal by Kamban. Her angika bhava as a teen princess was clearly defined as she played in the gardens and established a character that partakes innocently of life until she spots Rama. We see her transformed by that first look, Vidhya outdid herself in the depiction of tiny emotions that signaled an evolving sensitivity as a woman. Urmila was next, Gowri indicated this with a different angavastram. Her cadence changed, to that of a younger sister not quite understanding her fate. Gowri brought her out into the light, superbly narrated. Exit Urmila, Enter Sita: Vidhya then presented Eppadi manam tunindadho by Arunachala Kavi, where Sita asserts her will to go along with Rama to the forest. The last scene was especially telling, where she determinedly shows that her will overrides Rama’s. Before that, it could have easily been Urmila…to the uninitiated it looked like a debate she would have had with Lakshmana. The ceremonial umbrella was completely unnecessary here, especially since it seemed as though Sita was carrying it. Gowri’s brilliance as a writer/playwright was evident in her character sketch of Ahalya, which came next. The brilliance was both, in establishing her in the no-win situation of being married to Gautama - “Some say I was blameless…some blame-worthy …but I was just doing my duty” – and at her curiosity about Sita. Gowri’s Ahalya wanted to see who Rama married. The young boy who freed her, who did he deem worthy of being his wife? When she does watch them together, she believes at first that theirs would be a marriage that won’t be blemished by suspicion; noting that Rama is mindful of her, taking care of her, their marriage would survive – said with a twinge of the wishfull. As she exits the stage though, she says “…I hope.” Indeed, who else but Ahalya would know the treachery and hopelessness of fighting life’s circumstance? Exit Ahalya, Enter (one could not immediately figure out who it was): Vidhya came in inexplicably as a forest-dweller(s), reacting quizzically to encountering Rama-Sita-Lakshmana. The lokadharmi style of this beautiful Tulsidas piece (Kahan ke pathik), was wonderfully presented by Vidhya; the expressions of the leader, old man, and young girl, were exquisitely displayed. Next, Gowri’s Shurpanakha reminded us that she was born as Meenakshi, and posed the question: What kind of man (and by extension, society) would disfigure a woman for being bold and saying what she feels? If her Ahalya was brilliant, Gowri’s Meenakshi hurt. It showed a mirror to us as a society, and we didn’t look good. The depiction raised an unasked question as well: Wasn’t Ravana’s retaliation justified and in the same measure? Gowri has the astonishing instinct to make brevity amount to much more.  Exit Meenakshi, Enter Rama, Sita: This was the clichéd comic relief, except that it was dark comedy. Vidhya showed Rama and Sita as regular folks, in the Telugu folk song Ramamani, from Narla Venkateswara Rao’s “Sita Josyam”. It was surprising to see them address each other casually in sing-song; Sita even urges Rama to not fight the demons, since they needed to stay alive and go back to be King-Queen. This in itself took some swallowing (the popular notion of Sita does not allow this), but it was uncomfortable that something said so casually would have such disastrous consequences: Gowri’s Meenakshi had overheard this and felt emboldened to offer herself as a companion to Rama. That was the moment that kindled the tragic saga. Mandodari’s lament followed. It was elegant, and to those that didn’t know, underscored the fact that she had advised Ravana to not go after Sita, “the gem on the King cobra’s head.” Exit Mandodari, Enter Rama, Sita: Vidhya comes back in as Rama in Valmiki’s Ramayana, shockingly telling Sita that while he cannot accept her as his wife, she was free to consort with Lakshmana, Bharata, Vibheeshana, or even Sugreeva. A stunned Sita asks how he could be the descendant of the Greats, and yet be so small as to say this to her. Exit Rama-Sita, Enter two Sitas/poet, writer, voice of society: This segment should have jolted us the most, but lost clarity, perhaps because it was more verbose than the others. It started off well with translated lines from Indumathi Kaushik’s “Asveekar,” where Sita decided what to do about the letter. Then there was a dramatic segment with Vidhya and Gowri, both narrating as Sita, each from symbolically opposite riverbanks. This came off as esoteric. It didn’t compare with the thought provoking focus of the previous pieces. Perhaps something was lost in translation from the original, “Crossing the River” by Ambai in Tamil. Other aspects: Gowri’s accessorizing was spot-on. Vidhya’s needs some attention. Music was high quality and held up its side of the appeal. Priya Das is a writer based in San Francisco Bay Area, USA, covering extraordinary nuances of everyday life with a focus on the performing arts. She is a regular contributor to India Currents, a magazine reaching more than 170K readers on - and offline. Some of her writing is at priyafeatures.com |