|   |

|   |

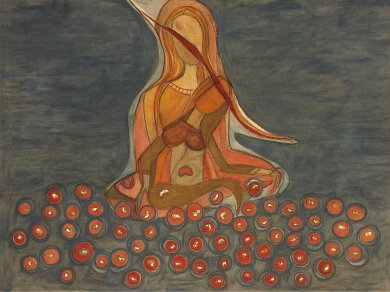

Pratidhwani: Echoes of Mahabharata voices through two art forms - Dr. S. D. Desai e-mail: sureshmrudula@gmail.com March 18, 2015 The significance of the values the Mahabharata characters represent fascinate practitioners of literature, performing arts and fine arts across time. A young painter, who has held many exhibitions of her works in Ahmedabad and Mumbai, and a reputed Kathak dancing couple, along with their four well-trained disciples, came together with their insights into six such major characters of the epic, five of them female, expressing them through their respective arts in Pratidhwani - an Echo of Virtues on Canvas. They express sentiments characteristic of the humans of this earth through the choices they have made in their art forms. Ruby Jagrut has done ten paintings in natural dyes, whose origin in antiquity goes back to the cradle of our civilization. And in these soft earthy colours, she chooses symbolic suggestions rather than two-dimensional realism. This lends character to her work. The portrayals do not lose the epic stature and universal appeal, each so good it could be on the cover of a book on the life story of the respective character. Ruby spent three years reading the epic, in her words, almost in a ‘meditative mood’ studying ten of its characters - the situations they were in from time to time, the crucial circumstance in their lives and their dominant emotion during it. It is this central circumstance and emotion that have been their identifying traits registered in the minds of the masses all through the years. While the ten portrayals were put on display for seven days at the gallery of the Hussain Gufa on March 10, by way of inauguration Kathak dancers Maulik Shah and Ishira Parikh-Shah with Namrata, Jigna, Raina and Kadam portrayed six of them. It wasn’t the strictly traditional Kathak format that they employed. The limitation of a little over six minutes they accepted for each portrayal, the full presentation being a curtain-raiser to the exhibition, became their strength. They lived up to the expectation and were economical and compact even while they symbolically combined dance, drama and choreography. While the painter subtly echoed the dominant emotions of the characters, the dancers identified those emotions, gave them a context and perspective and through the convenience of their medium, re-echoing them they established them as part of life.  Draupadi  In rehearsal In the painting, Draupadi emerges in the dark as she is being disrobed, trying to protect her honour, symbolized by a faint vermillion mark on her forehead. The relative composure that comes through her raised praying hands shows the power of her character and the loose long flowing hair besides reminding the viewer of her vow reflects her sensuous beauty as well. The faceless male faces in the Sabha (did they all turn white?), including the five with heads held low, and the dice reveal the context. Modern interpretation In the dance the focus remains, and the spectators’ eyes transfixed, on Draupadi’s face, which red with controlled rage inescapably expresses humiliation besides the anguish of a woman in such state and her dheer-gambheer demeanour her distinctive personality. Ishira as Draupadi significantly through a glimpse of aamad shows her silent reproach to those dumb in the event of values getting demeaned. The reassuring moment is in her hands raised in prayer with the ringing single word Narayana repeated. Even as the moving Sudarshana Chakra on Krishna’s steady tarjani appears from the right wing, in a noteworthy modern interpretation, two girls, representing as it were a conscientious society, enter and wrap Draupadi up properly. There is an interesting depiction of the bust of Hidimba in ‘close-up’ with an elongated nose, large rolling eyes, curved broad lips and a big round vermillion mark - an Amazonian young giantess but a woman nevertheless with flowers reflecting her tender feminine feelings. On the stage, the tallest (also the thinnest) of the dancing girls Jigna takes long strides with alacrity and is given higher levels to jump onto. In the empathy extended to her, one is reminded of the modern attitude to individuals normally looked down upon in society. According to the epic story, she had the mighty Bhima enamoured of her. With a slender figure of the dancer, clenched teeth and pouncing claws of the character, well-established in collective memory, were better left to the imagination of the viewers, particularly when a tender aspect of her being is sought to be projected.  Hidimba  Kunti Kunti’s unspeakable guilt of having had an illegitimate son Karna, her first offspring, and having floated him away to his fate, which haunted her all through life, is writ large on the face of her image within the larger image of a ‘respectable’ mother of the Pandavas, whom she sees in flowing water too unanchored before the battle. The underlying irony of the opening of the performance with aadityaay namah cannot be missed that the universal source of life and energy has become the cause of remorse for Kunti, enhanced with music (Neeraj; Nishant-Jignesh). The agonizing conflict the mother faces gets highlighted with the Ginati aavartan of ek-do-teen-chaar-paanch and ek. Echoes frozen, re-echoed  Amba All human sentiments are said to be depicted in the Mahabharata. A beautiful princess, Amba on finding her love repulsed both by Shalva and Bheeshma, with no consideration for her, lets loose her passion to avenge humiliation. Though born again as a girl, Drupad’s daughter in the next birth, through tapasya she grows into a gallant warrior Shikhandi and has his (read her) revenge against Bheeshma in the battle. The two diametrically opposite qualities are presented in contrasting colours in the painting and through a visual narrative on stage. In both, the strength of the character of Amba, whom readers tend to relegate to the background of the epic story, gets recognition.  Gandhari

All that comes to an average reader’s mind is the ‘Sati’ image of a blindfolded woman as Gandhari. In the enormity of the intensity of her sensitive being within and the value of nonverbal suggestion an art work makes, Gandhari is outstanding among Ruby’s character portrayals. The dark red strip of the blindfold across her visage and the face of the invisible being (made visible) inclined to her left and the navel, to which the umbilical cord of each child was connected, give an idea of her tearing emotions. She is made of such stuff that her sensitivity encompasses not only her husband’s pain and the death of her hundred sons, but also the loss of values in the Draupadi episode. Theatre needs contextual narrative details to bring home to the viewer the intensity of the feeling depicted, and music and lights generally to enhance its effect. The circles with the suggestion of life within get turned into brightly lit tiny bulbs (Lights: Abhishek) in the performance and, tuned to the somber strains on the violin, Gandhari’s indescribable pain gets subtly conveyed in slow motion. Under the blindfold, Ishira as Gandhari recalls to mind the momentous unfortunate circumstances that gave an unalterable turn to the fate of her family and clan - and the people of this land for all the time to come.  Krishna

Krishna is the central figure of the Mahabharata. In the painting on him is given a pictorial summary of major events and characters from the epic and the values he is known to represent in it - symbolically, the Dharma Chakra, the Mayoor Pichchha, the Fish, the Bindi on the Forehead of a Woman, the Wheel of Fate, the Dice, The Pandavas, the Kauravas, the Arrow and so on, most associated with our folklore and ethos. However, they are not quite subtly suggestive as in most other paintings. The dance performance briefly sums up the eventful epic narrative with Krishna, radiantly played by Maulik, in the centre. In this piece and the rest, the four trained disciples - three girls and a boy - are expressively part of the moods and situations depicted.  Pratidhwani reaffirms in an exploratory way what is often heard said that what is not here, in the Mahabharata, is nowhere else. The epic has been occasioning from time immemorial, as in the Whispering Gallery of Bijapur Gol Gumbaz - to give an elementary analogy - multiple echoes in different art forms. The echoes received and frozen in colours in Pratidhwani get re-echoed in a dance form, which has the felicity of movement and abhinaya. It is difficult to recall a parallel to a combined creative endeavour of the kind. Dr. SD Desai, a professor of English, has been a Performing Arts Critic for many years. Among the dance journals he has contributed to are Narthaki, Sruti, Nartanam and Attendance. He guest-edited Attendance 2013 Special Issue. His books have been published by Gujarat Sahitya Academy, Oxford University Press and Rupa. After 30 years with a national English daily, he is now a freelance art writer. |