|   |

|   |

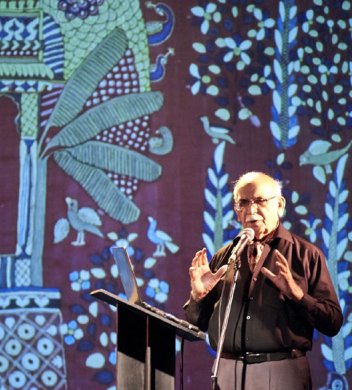

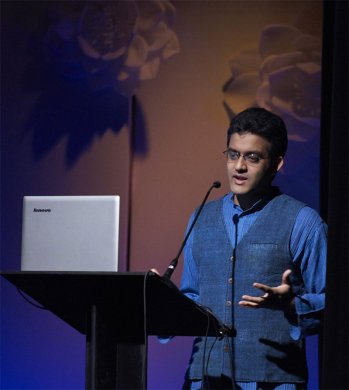

Natya Darshan 2014: A sum up - Devina Dutt e-mail: devina@firsteditionarts.com Photos: Lokhii February 3, 2015 The idea of using the blossoming lotus as a metaphor for the chain of creative processes that are triggered when a new artistic work is being made was an inspired one. Dr. B.N. Goswamy whose deep and unaffected scholarship spans Urdu, Persian, Sanskrit poetry and art, chose a poem in Urdu by the Pakistani poet Ahmad Nadeem Kazmito to expand that idea. Ilfaz ki haisiyat phulon ki si hotee hai Jo shair ki kuvat e takhleek ke mutabik Apne pakhriyon ko kholte hain ya samethe hain Words are like delicate flowers Gauging a poet’s intentions and capabilities Their petals open up or gather close together. As the principal architect of this conference, Malavika Sarukkai’s own dance presentation ‘Vamatara: To the Light’ on the first evening reflected her curatorial concerns and intentions in a robust and direct manner. Linking the blossoming, gradually flowering lotus to the creative process was an opportunity then to understand how a performing artiste is shaped by the multiple ideas and influences that come to bear during the making of a work. It was also a time to retrace the roots of the process by which music and poetry are a part of the improvisations that define the Indian classical dancer.  Dr. BN Goswamy  Malavika Sarukkai All of this was suggested by Dr. Goswamy, a constant intellectual and aesthetic presence at the conference. On the very first day, he took us to the Vaishnav town of Nathadwara and its splendid pichwais in a lecture on art and the creative process. Pointing to a visual of a cave, he referred to it as the cave of experience, adding that, “Every time you enter that cave, something will happen…” Once again guided by Dr. Goswamy’s inner eye, perhaps the empty space left for Krishna in the pichwais too has a purpose. The fact that the painters of pichwais painted him ambiguously, sometimes as a shape barely seen through the stream of golden yellow leaves falling off a tree, tells us that when we are experiencing art, meaning reveals itself gradually and in flashes. The empty spaces in the pichwais are also a reminder that audience response is the final turn of the key for the creative arc to be complete. I think we saw a great deal of that wealth of creative processes in the two sessions with Bharatnatyam dancers Shyamla Mohanraj and Aniruddha Knight. Not surprisingly there was a direct connection between them and the great dancer T. Balasaraswati; the former is a long standing student and the latter is her grandson. Both are steeped in all that they have learnt from the great dancer and musician and their lec-dem sessions on ‘Abhinaya’ and the ‘Musicality of Dance’ respectively, were riveting.

Vidya Sankaranarayanan

I would add Vidya Sankaranarayanan’s fine all too brief performance on the last day to the group of distinctive performances. This was dance that despite its extreme stylization was somehow also informed by the everyday in an inherently natural and dignified way. There was no mention of faux spirituality (cosmic, space, sacred, inner, transcendental, divine, sublime, bliss…you get the drift!), words that are used too easily and frequently by many dancers. The vocalist Usha Shivakumar common to all three experiences even to my untrained ears, made a difference to the quality of the experience. We got a sense of the fullness with which the traditional dancers must have approached their dance. I loved the fact that Shyamala was visibly unused to talking and wanted only to get back to dancing! We saw textures and shades that are not to be seen anymore. It was a reminder of all that was lost in the curious social revolution of post Independence India which saw hordes of dancers from the elite and burgeoning middle classes take to the form. This was an inevitable outcome of the nationalistic project which had sought to revive and cleanse Bharatanatyam so that it might fulfill the need for cultural pride in a new nation. But it could do so only by flattening out its complex history and the true scale of its achievements as practiced by a consummate and hereditary artiste of Bala’s stature. It was impossible not to feel a very powerful regret for what has been lost of that greatness.  Shyamala Mohanraj & disciple  Aniruddha Knight It struck me that although Aniruddha and Shyamla seemed to extend emotional content they never seemed sentimental or mundane. Shyamla with her subtle abhinaya, her use of hand and wrist movements had a style we miss. Aniruddha and his musicians and their emphasis on music, of being in-the-moment performers devoid of any self aware artistry as well as a tempering of geometry and correctness with roundedness, indicated to us Bala’s fully achieved genius and achievements. It gave us an idea of their creative processes though I suspect that they themselves would balk at calling anything a creative process. And yet how deeply they considered every choice. Aniruddha narrated the incident of Bala and her mother, the ace musician Jayammal changing the raga of the kirtanai addressed to Lord Ranganatha, Yenn palli kondirayya from Mohanam to Madhyamavati because they felt that the latter reflected the dissolution of the self in the devotee better than the former. How sharp were their instincts for making changes in supposedly traditional material. This offered us an insight into our simplistic notions of the apparent rigidity of all that constitutes tradition. It reminded us also that the creative process in the past as well as at present is as much about leaving out things as it is about leaving the right things in. Today, unfortunately the same dance in many cases though not all, often seems to exhibit its own problematic and unresolved relationship between past and present or maybe I should say many pasts and many presents, all at different intervals of time. A great deal of work therefore appears too literal, conformist, mimetic, merely conventional rather than truly, richly traditional. At its worst it is even juvenile and embarrassingly simple minded as was evident in the majority of the Bharatanatyam performances at the conference with awkward unformed ideas. The worst moments were those when some indifferent multimedia elements were forced into a performance. The wonderful paradox of the classical arts with the tension between their moorings in cultural pasts on the one hand and the perpetually contemporary strain that runs through it on the other lies largely unexamined. It was worrying therefore that many dancers chose texts which mentioned lotuses in various stages of blooming... The tediously earnest explanations in the festival brochure could not obscure the fact that the performances were just a straightforward depiction, a simplistic business of finding the appropriate or matching actions for words. Dance as interpretation, an imaginative flight or an oblique choreography with an investment of the intellect or an exploration of true aesthetic refinement was missing.The dancers were earnest, eager to please and had the best intentions but to me such dance seems such a waste because it does not and cannot move us or surprise us either aesthetically or intellectually. I wonder if a strict adherence to purely physical recognizable external elements of the dance has not become a way of asserting notional loyalty when the more subtle ideas are difficult to commit to. In such a context the greatest music and musicians as well as poetic texts run the danger of being reduced to mere cultural markers. Borrowing a concept from the world of theatre and contemporary dance, I wonder if a dramaturge could work with classical dancers and particularly with the younger Bharatanatyam dancers of today who seem more cut off from the rich cultural ideas, practices and textures that are necessary to feed their minds and choreographic imaginations. It is a fact that many classical dancers tend to work in self imposed isolation, warding off external influences, creating their works surrounded by friends and supporters but rarely a critical and sensitive outsider who is capable of thinking of how it will be received. There are many among those who come to the dance as new viewers who want to relate to it but are put off by mere sanitized prettiness or a frequently proclaimed spirituality which cannot even go deep enough into the very tradition it claims allegiance to. The great gurus of the past are of course irreplaceable. Thanks to co-curator Prof. Hari Krishnan for the glimpses we got into their methods and techniques with the excellent film clips. In telling the story of Gauahar Jaan, Vikram Sampath reminded us of the ways in which history, context and politics shape an artiste. This was also a perfect cue for Gauri Sharma’s minimalist presentation of a kathak thumri.  Vikram Sampath  Anita Ratnam  Geeta Chandran  Gauri Sharma The discussion with Anita Ratnam, Geeta Chandran and Gauri Sharma was an interesting one and I wish it had gone on longer at a conference meant to discuss the creative processes. Anita’s ability to reflect her personal story in her practice was in keeping with her choreographic journey. Geeta Chandran’s tribute to her guru and her singing was heartfelt and Gauri’s ability to create site specific works while working within the Kathak tradition in the UK was intriguing. I wish we could have had more of this session and others which dwelt on the creative process. One of the questions or sub texts that emerged from the conference was this; as a classical dancer what was the better way of serving the form. Should a dancer remain committed to taking dance from one generation to another as a simple transfer of legacy? Or is it a dancer’s duty to attune herself to the contemporary world and fashion a riskier, more individuated response, making changes that he or she deems creatively necessary at the time relying on judgment and experience to show the way. Perhaps both are needed in different measures. The first approach though runs the danger of mistaking its own satisfaction at serving the ideas of correctness and purity as a sign of serving the long term interest of the dance. Some of these issues were addressed in ‘Widening Circles,’ the keenly assembled three part production by Kathak dancer Aditi Mangaldas. At the core of Widening Circles (from the poem ‘I live my Life in Widening Circles’ by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke) lies the most superlative poetry and the Buddhist concept of pratitya samputpada or the interconnectedness of everything in the Universe. The production was a fine example of what can be achieved when an artiste treats a given idea as the beginning of a process of exploration supported by a freeing imagination and makes carefully deliberated artistic choices at every stage. Every creative decision regarding the use of costume, musical arrangement, choice of poetic text and light design is refracted through a sensibility which can allow thought and lyricism to co-exist. The three part production with a section each on the Sun, Earth and Moon brings together poetry from the Katha and Prashna Upanishad, a couplet from Ahmad Nazim Qasmi and a song by Meera. In addition, there were parts where she recited poetry by Tagore and Rilke. But so thoroughly thought out was her material and her dance that it was never an exercise in self-conscious eclecticism. Neither was it simplistic or simple minded. Clearly, months of staying with the idea and a very personal exploration and investment in each creative stage had formed a part of the production. And despite a paring away of the fussy costuming of “conventional” Kathak dancers, there was never any doubt that this was a kathak dancer using her knowledge of the form to follow her mind and choreographic design. There was no mistaking the spontaneous audience response for her piece because we all sensed something new and honest and creative had been attempted. Of course this is only one way of speaking to an audience and specially new audiences for the arts outside their immediate contexts. But there are many other ways of seeing, creating and presenting and many cues lie buried within what we have grown accustomed to referring as our cultural heritage.  Aditi Mangaldas  Lakshmi Vishwanathan Lakshmi Vishwanathan’s talk on the great cultural achievements of Thanjavur was a marvelously spontaneous oral history experience dramatically but beautifully expressed. Her concluding remarks about driving to Thanjavur today as opposed to walking there in the past, savouring its lotus filled ponds and learning to live a life of goodness and attuned to culture was a reminder of the underlying values that lie buried within the traditional and classical arts and need to be articulated from time to time. Provided of course we have the ability to situate ourselves within that tradition and draw from it intelligently and sensitively while remaining open to the times we live in today. Provided we don’t pursue an idea of sterile perfection allowing ourselves to be influenced by the anxieties and politics of the modern world too since we are a part of it.  Sadanam Balakrishnan, L. Sabaretnam, Malavika, R.Sekar, Hari Krishnan  Sadanam Balakrishnan Guru Sadanam Balakrishnan who received the Lifetime Achievement Award shared his anguish at the frequent blurring of lines in performance today between the strictly demarcated rasas. Speaking with the authority of a true Master, his remarks showed the role played by correctness and rigour in the classical arts. The shringaar rasa, he pointed out had to be undershot by anticipation and an expectation of a union with the loved one. If the right amount of hope was not shown it could come dangerously close to karuna or sorrow whose essence is very different from the mood of love of shringaar. Karuna too, or sadness could not be mistaken for compassion though it often was, he regretted. His was a voice of great artistic experience and wisdom that can only come from experience and years of just being his art. His approach to his audience is open and accessible as he remains interested in how the audience is receiving his work even as he insists on remaining true to his artistic vision. This is the reason that he is able to speak to his audiences and win over new viewers. Devina Dutt is a Mumbai based arts writer, editor and curator. She is the founder and director of First Edition Arts, a Live Arts promotion company |