|   |

|   |

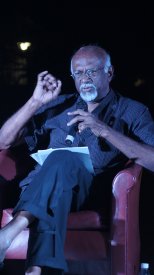

DanSe Dialogues - Shveta Arora e-mail: shwetananoop@gmail.com Photos: Anoop Arora July 27, 2014 To mark the conclusion of DanSe Dialogue, the Indo-French festival of contemporary dance, the ambassador of France, Francois Richier, hosted a discussion on ‘Locating Dance in India: Between Tradition and Contemporary’ moderated by Alka Pande. The panellists were Leela Venkatraman, Shobha Deepak Singh, Sadanand Menon, Justin McCarthy and Deepti Omchery Bhalla. The discussion was held on the 7th of May at the residence of the French ambassador. The lawns were lush and sprawling, but the weather was hot and sultry. It was only when the talk started that one got over the misery of the weather. The speakers: LeelaVenkataraman: For people in the world of dance, she does not even need an introduction. She’s been a dancer and dance critic for the National Herald from 1980, but right now she is writing widely for a number of publications. She has written books, is one of the most well-respected critics for the Hindu, and her next book, After Renaissance: The Last 60Years in Indian Dance, is going to be out soon. Justin McCarthy: He’s of American origin, but we now forget that because of the number of Indian languages he speaks. A noted Bharatanatyam dancer, instructor and choreographer, he teaches Bharatanatyam at the Shri Ram Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi. He’s also a classical pianist and adept in Carnatic music. Shobha Deepak Singh: Known for wearing many hats, she’s a photographer, choreographer, chairman of the Bharatiya Kala Kendra, and is running with tireless energy the Kamani auditorium. Deepti Omchery Bhalla: She’s teaching music in Delhi Uni and doing a lot of intense research with her mother into several dying forms which she has choreographed and presented in Mohiniattam. Sadanand Menon: A nationally reputed arts editor, teacher of cultural journalism, widely published photographer and a prolific writer who speaks on various things from politics, ecology, cinema and the arts, currently faculty at IIT Madras and at the ACJ in Chennai.  Alka Pande: DanSe Dialogues has been a wonderful festival and today is in some ways a closing of this. What makes me happy is that Shobha Deepak Singh, whose book Dancescapes was done last year, is featured here. Justin who’s part of the book is also here. It’s interesting in these days of specialisation, in which we look at many things as dance, painting, music, etc. But in India, we go back to the Natya Shastra, which in itself is the coming together and in many ways part of the post-conceptual way of looking at the arts, where scientists are looking at paintings, chemists looking at sculptures. This panel is looking at dance from their own individual trajectories. We may ask, what is contemporary dance? Not an easy question and this is what we will debate here. What defines contemporary dance? One thing definitely is that it is a radical break from what we in stereotypical terms call the classic. Because contemporary dance is relatively nascent, it is unequivocally up to date and doesn’t hesitate to meld (together) art, music, poetry, imagery, fashion and even a bit of trapeze, as you saw. In some ways, it is also a re-conceptualisation of classical forms and contents. Some examples of contemporary dancers who have done this and have come to India are Cunningham, Pina Bausch from Germany, and Maurice Bejart from France. Contemporary dance in some ways is a 20th century phenomenon. Free from the rules and regulations of ballet, choreographers sought to invent new forms, as yet nameless, which later came to be grouped under this wide, generic name called contemporary dance. Contemporary dance in some ways reflects the zeitgeist of our times, cultivates variety, combines several kinds of art and incorporates various influences. In the globalised world, DanSe Dialogues stands as a model of intensified cultural exchange between France and India, where contemporary dance reinvents itself by the influence of two cultures to produce a unique performance. In Hindu mythology, dance was believed to have been conceived by Shiva, and he inspired Bharata muni to write. In some ways, Brahma also entered the fray, and the Natya Shastra was written – a treatise on performing arts from which the codified practice of dance and drama emerged. We will have different people coming from their own practice, talking about what they feel is their journey of dance. We tried to think of a title that could encompass this whole huge geography of dance, and we called it ‘Locating Dance in India Today: Between Tradition and Contemporary.’ Alka Pande to Leela Venkataraman: Given the context, there was aninteresting remark – you spoke of integrated education. As someone who’s been watching, reading and writing about dance, could you explain what you meant by “we are today missing out on integrated education” and what you have been witnessing when you look at dance.  Leela Venkataraman: In some ways, I’m here under false pretences because I don’t profess to being an expert on what is called contemporary dance because for me, a classical dance is contemporary, something which a lot of people may not agree with. Now, you referred to the Natya Shastra, and you talked about the way in which different parts of the body have been described in it. If we go through certain parts of the Natya Shastra, I think it is absolutely contemporary. It tells you to isolate each part of the body and it’s been discussed how the body can be used. So I don’t know what is so old fashioned about the Natya Shastra, and what is so old about the classical dances. Yes, they are stylised, they have a certain format within which people perform, but to say that all classical dances are absolutely old and we cannot think of them as contemporary is something I do not subscribe to. Because even in the beginning, when modern dance, as it was called, was thought of by somebody like Uday Shankar, he first went to the classical dances. He first learnt classical dance and out of that, he started making his own body movement. And this was not a person who merely took the ‘exotic’ Orient to the west. He did work in his film, if all of you have seen it, a wonderful dance called ‘The Labour and Machinery’ where he created an entirely new movement. He’s talking about what mindless industrialisation can do to this body, making it a kind of robot. And a lot of westerners who have seen it have said it’s not even modern, this is postmodern. Now I think when you learn a classical dance, if you understand it thoroughly, not only its history but the language that goes into its making, the literature, the surroundings from which it comes, how it really connects with reality and the modern world, how it has developed over the ages, then I think you can make it absolutely modern. There is nothing old about it. And this is the kind of education which we do not find today, because a lot of schools merely teach the students how to take the technique of the dance. The body technique is shown, but nothing else is known to the students. When you do that, you are limiting their understanding. And when I say dance in its entirety, classical dance, then I think it is absolutely contemporary. For instance, Chandralekha. She used the vocabulary of Bharatanatyam; she didn’t go to any other dance form. But through Bharatanatyam, it was a voice of resistance, and she found the connectives in yoga, she found it in kalaripayattu, and what she created was for me, very modern and something which at that time I did not even understand. But there are a lot of classical dancers who are doing this. Sonal Mansingh does something that is absolutely contemporary, the entire repertoire that she created in Oddisi. I’ve seen Geeta Chandran do some wonderful work with Bharatanatyam. She did one called ‘Revisiting Mythologies’ and I thought that was one of the most wonderful things I’d seen and it made a very contemporary statement about the young girl child being aborted while still a foetus and why this happens in this country. And I thought the entire story, and the entire statement that was being made was very contemporary. This kind of work is being done by a lot of people. So what you exactly mean by contemporary, I think exists in layers at various levels; it’s a question of what you really understand by the word contemporary. A lot of contemporary dance from the west is something that I’m not able to relate with, I can tell you very frankly. But a lot of the work which I see today, pushing boundaries, trying to do something new, is very contemporary. I think Sadanand Menon will not agree at all because for him, we are still completely lost in the old traditional format and we refuse to get out of it completely. But the very word contemporary I think is a relative term, and even though I’m a writer on dance and I’ve been using words like contemporary, classical, traditional, modern – all these we use with impunity - but then you find that these are relative terms, and there is no fossilized thing which you can call classical. I mean, they don’t exist in isolated spheres which don’t meet at all. One melts into the other, and this is happening all the time. And on the modern stage, when you are trying to relate with reality today, when you’re trying to communicate with a cosmopolitan audience, when you’re trying to preserve your cultural identity – I mean both personal and regional – then yes, I think you are pushing the boundaries and you are doing something which is contemporary. Alka Pande: This gives me a beautiful bridge to Justin, who in many ways epitomises the cultural identity of what we call today a global cosmopolitan artiste. He’s ‘from the soil’ in some ways, because we also believe in a karmic distribution. Justin is more Indian than any of us. What do you feel today about dance in India?  Justin McCarthy: First, the idea of a global citizen, someone who appreciates many different cultures, is an old idea.The world has always been lucky to have people who cross boundaries and I am very grateful to be in this country. It is known that when in the 19th century revolution came about in the west in the art forms, it was under the influence of either Asia or the East and Africa. In music, it is known that contemporary music was under the influence of Asia and in visual arts painters like Picasso looked towards the East. In dance, the devadasis from south India travelled as far as Europe and the Coney Islands in America in the 19th century. They looked towards India for liberating influences. The modern American dancers travelled to India in search of a modern form of dance. It is in fact very paradoxical that in India evolved the contemporary dance vocabulary. In this context, I would like to talk about Chandralekha. When I say Chandralekha, I mean the triumvirate of Chandralekha the dancer and choreographer, Dashrath Patel the graphics designer and Sadanand Menon the writer. Her work, though contemporary, was deeply rooted in ancient dance form as Leelaji said, with a feeling of liberation. She incorporated kalaripayattu and yoga. She used the Bharatanatyam vocabulary. All of this was the sound ideological base; with Sadanand, Dashrath and Chandralekha having very strong political feelings, the work was highly political. Before that, I believed naively that Bharatanatyam was not terribly suitable for political statements, but their work certainly challenged that view. So for me, their work was certainly the high mark of maybe the modern or contemporary classical work done in the 20th century. And then, as far as contemporary dance goes in India, I think it’s a really exciting and very different time now, because there are lakhs of young people all over India who want to plug into what is globally known as contemporary dance, so I think that’s changing the scene a lot. Even modes of communication have changed – the way people walk or use their bodies is changing as globalisation looms large over the world landscape. It’s wonderful that France and India have come together to celebrate the contemporary. In Delhi, there’s a wonderful organisation called the Gati Dance Forum, and that to me is doing the best work I’ve seen in contemporary because they’re open to all whims, they’re even open to the classical whims as well as contemporaryfrom the west, east, north, south. Alka Pande: I know Shobha as a documenter. We have worked together on two books - I know her as a choreographer, a cinematographer and an archivist. Carrying your camera tirelessly to photograph dancers, sometimes to their dismay and sometimes to their wish to be documented, I would like to know of your reading of dance from behind the lens. You have learnt dance, choreographed it, are running ballet festivals, you have been doing the Ramayana for so many years...  Shobha Deepak Singh: I have been doing photography for 40 years and when I was told I was to express my views here, I picked up a few dancers and followed their images over years. I found there were a lot of changes over time, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. We brought about a few changes in the Ramayana as well, like making Sita wear a sleeveless blouse. When I was questioned about that, I said that in her time Sita probably did not wear a blouse at all, probably just a piece of cloth. Similarly, when we redesigned Krishna from the perspective of Mahabharata, we see divine folly becoming the conqueror of war, which is as pertinent today. The Kendra has done two productions which are totally out of step with mythology. The first is Parikrama, which is the journey of the soul through air, water, earth, fire and ether, and then into the womb of a woman and taking birth as a human and going back. It was a challenge to show the theme. And then we did Masks, where a boy and a girl belonging to different social strata fall in love. But it is the society that does not let this happen and conquers. Photography has taught me a lot of things. Because of the lakhs of prints, I can trace the development of a dancer. I have done audio and video recordings of Chandralekha as if there were no tomorrow. I can say with conviction that dancers and choreographers from the south are better. Therefore, in our quest to do something better, we have shown Attakkalari and Prayog from the south. I hope the audience will appreciate our effort. I hope to continue photography, which is my passion, and hope to capture movement rather than fair and lovely photographs. Alka Pande: Shobha just said that she prefers dancers from the south. Today, we have Deepti Omcherry Bhalla, who is an institutional person teaching Carnatic music in the Delhi University and also an excellent Mohiniattam dancer. While we were debating on how some institutions are stifling talent, inventiveness and innovation, Deepti came out in defence, that institutions are producing rasikas, one who is enlightened enough to appreciate and understand a performance in its right perspective. Deepti, would you like to share your thoughts as a dancer and the double hat you wear as an educator?  Deepti Omcherry Bhalla: First as a dancer, I would like to talk about the change from the time I was being taught to the present repertoire that I perform, whether it comes under the contemporary or the traditional. The change has been very gradual and has happened naturally and unconsciously. When we talk about effective and educative choreography, I try to justify that. Mohiniattam as the dance form we know of, after its revival in 1930, is very recent. My effort has been to delve into its past and I have not paid much attention to its modern context. My effort has been to enhance the existing style of dance rather than giving it a different structure and style and calling it contemporary. When my teacher taught me, it was a very small repertoire and the hair had to be tied at the back; my teacher was very particular that the hair be tied behind. The movements were mostly forward and backward because we could not avail of much space. Since she was very particular that every expression and every movement should be very subtly portrayed, if you cover too much space and do too much movement, it gets lost. As I grew as a dancer, I realized that Mohiniattam required certain changes to bring out its innate, inherent qualities. So the side hairdo was one and having a repertoire similar to another dance form was another. I changed the repertoire to be closer to the dance and music of Kerala. On the other hand, I realized that if we present a pure dance piece, we will not be able to reach out to a larger audience or rasikas. So I have worked on certain ideas and concepts with a friend of mine. We worked on poetry by an eminent Malayalam poet and called it The Fallen Flower. We performed it at the Kala Ghoda festival in Mumbai. The poetry is about a flower which grows from the earth, blooms like a beautiful maiden and then shrivels and goes back to the dust. For the portrayal, we used music, lights and body movements, she in Odissi and I in Mohiniattam. We brought both the elements and evolved the whole concept and the critics appreciated it. Similarly, we did Geeta Govindam in Delhi based on Hindustani music and I had to change my movements to suit a huge space. Of course, the puritans did not like it. But Leela-ji was with me and asked me to meet the demands of the space. These are the challenges we have to face while choreographing. Regarding the institution, I started the FOM to sensitize the students enrolled to the finer nuances of music. If a person listens to music day in and day out, his ears get tuned to the nuances and subtleties of music. Earlier, this was possible because AIR had classical music concerts and devotional songs playing all the time. That would help to tune your ears and blend your voice to create that perfect note, which brings the ecstatic experience or ananda, and understand the importance of shruti and not turning them into performers par excellence. We also have programs for students who do not want to take it up as a profession but, like opening a recording studio, they have to be competent. The students don’t necessarily have to take up singing and teaching, but can take off and evolve. Alka Pande: I request Sadanand Menon to speak from his trajectory and wrap up the discussion. He also wears many hats, like his colleagues here.  Sadanand Menon: I would like to thank my co-panellists for weaving a garland that is connected but in a broad canvas. I would like to flag the possibility of naiveté creeping into a discourse like this where we use terms like ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ in a very naturalistic manner, as if there was once a tradition which grew to become modern which grew to become post-modern and then contemporary - as if these were beads in the rosary of history with a linear thread. The use of these categories is problematic. You do not see this kind of distinction in the study of films, music or other art forms, but particularly in the history of dance this is a problem, that of not being able to engage with the history of dance. How do you reclaim your past to bring it to the future, which has been done in other disciplines? The idea of traditional and contemporary, particularly in the context of Indian dance, are constructs. They are not historic givens, they are constructs. If we recall, circa 1929, E Krishna Iyer recreated Sadir natyam and Dasiattam and called it Bharatanatyam, and two years later, Rukmini Devi Arundale institutionalized it; if we pick it up and call it traditional, we are living in some kind of historic blind alley. This is a modern moment and as Justin said, some kind of global exchange. It is a modern construct and our inability to see it as that has been making the Indian dance discourse go into a backward pedalling mode. We have lost about 60-70 years of not being able to honestly engage with our history. For this, we need to do the kind of work that Shobha did, sitting and archiving history in your camera. That, for example, is the beginning of modernity – creating an archive – where you can actually look at the passage of time, the way bodies have changed, past and present, look at the idea of movement of time in the body. To give an interesting example, there is no documentary footage available in India, for example, of what devadasi dance in India was in the 1920s. We have footage from Uday Shankar’s film ‘Kalpana’ but that was in the 1940s. We don’t know what this dance was, which was so reviled – they were called prostitutes, they were called chi-chi dancers, they were despised as nautch girls. What happened in the reconstruction in the body, as it were, in the year ‘29-30, with the arrival of the Brahmin bourgeoisie upper class upper caste into the arena? To find the answer to that, you have to travel all the way to America, to the Jacob’s Pillow archive – a wonderful dance institution – where you actually have footage of what the dasis were doing in the 1920s, let us say. And what were they doing? It was fascinating – you’ll find that reconstructed Bharatanatyam is an upper torso dance; the dancer virtually behaves as if there is no bottom. As my great dancer friend Suzanna used to say, where is your poposh? It’s not worked out in that form because there is a certain kind of attitude about showing the posterior, this part of the body is all taboo, this part is better, etc. You see the footage of the devadasi dancers and you’re stunned by the extraordinary mobility of below the torso. So it’s a kind of lobotomy, a plastic surgery, where the body has been cut and pasted, and suddenly from the 1930s onwards you see only upper body work and the lower body doesn’t work. These are issues which I think dancers, teachers, historians and all the fraternity and stakeholders of dance have to collectively engage with, because this is where the crux of the issue lies – how does one excavate from the material available and create a vibrant present and future? The reason why contemporary dance assumed a certain importance today is because it seems to be accommodative of far more identities. You deal with emotional material like desire, love, agony, longing, reconciliation, waiting etc. The correlates of that is in the body, which could be balance, stretching of time, stretching of the body, slowness, control, breath etc. This is common material for anybody who works with the body, whether it’s a tribal dancer in a Gond village or it’s a modern dancer on the American stage or a classical dancer on the Indian stage or from any part of the world – this is common material. But the question is, what is one then doing with the body? In the classical form, the approach to the body is an idealisation; it’s a particular aesthetic that has been inherited, an aesthetic of the bourgeoisie which finds a particular kind of beauty in symmetry, balance and so on. This is what modernity cuts into. I think in the contemporary movement, the quest of the younger dancers, who don’t necessarily come from specific schools, who don’t necessarily acknowledge gurus, who don’t necessarily come from particular gharanas, take from anywhere they want, in a mixed bag as it were. The kind of stuff one sees on the program Sonal Mansingh is anchoring on DD today – Rum Jhum– one sees all sorts of body movements that are possible. This is a quest towards not idealisation, but a different path called humanising the body. And in these times, this is what artists are searching for - how does one humanise the body, the work, how does one bring rasa into the work, and that I think is the ultimate quest. Shveta Arora is a blogger based in Delhi. She writes about cultural events in the capital. |