|   |

|   |

Of Heads and Tales - Chitra Sundaram e-mail: chitra@chitrasundaram.org Pics: Vivekanandan December 29, 2013 ‘Purush - The Global Dancing Male’ conference and performance conclave Company: Adishakti Laboratory for Theatre Arts & Research, Pondicherry Works: The Tenth Head and Nidravathvam Venue: Alliance Française auditorium, Chennai Dates: December 18 & 19, 2013 Apparently quixotic questions and physical theatre prowess underpin the substance and form of two plays – The Tenth Head and Nidravathvam (sleep) – from the stable of Pondicherry-based Adishakti Laboratory for Theatre Arts & Research. Staged at the Alliance Francaise, Chennai, they opened ‘Purush – the global dancing male’, the third Natya Darshan dance conference and performance conclave convened by Anita Ratnam for Kartik Fine Arts and Arangham Trust. Performed by their playwright-actors, Vinay Kumar and Nimmy Raphael, the narratives are delightfully idiosyncratic, providing unusual diversions from the epic tale. Vinay’s exposition deals with the issues arising from the Ramayana’s anti-hero Ravana’s having an even number of ten heads, not, say nine or seven. Nimmy’s ‘Nidravathvam’ throws Kumbakarna (sic) and Lakshmana together on the battlefield and they exchange laments and notes on sleep or lack thereof. (‘Does this actually happen in the Ramayana?’ someone wondered aloud in the aisles after the shows. Nope. And that’s where inventiveness comes in as a hallmark of this theatre company.) The re- or new-tellings are rendered plausible and entertaining by the performative presence and robust theatre craft of its main actors, and a script sparkling with wit and irony.

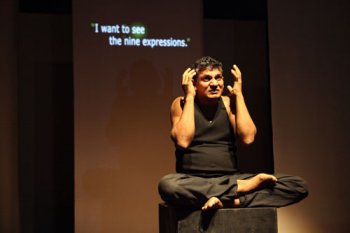

Anita Ratnam, Vinay Kumar, Veenapani Chawla In Vinay’s ‘The Tenth Head’ directed by Veenapani Chawla, the even number of heads pose a fundamental balancing problem due to the laws of physics on the one hand, and the aesthetics of symmetry in the human or animal form. In other words, nine heads would give him one in the centre for a ‘complete’ human figure, and an equipoised four more on each side, for meaning and interpretation; one more on any one side and the body cannot balance, as gravity will pull the heavier side down. The ‘tenth head’ is thus an aberration, or unnecessary and, importantly, the tenth head thinks so too! Vinay plays Sutradhara and the tenth head, amidst on-screen animated presences floating de-bodied in ether and projected on the several partition-screens that also serve as a set. Unsuprisingly, this ‘extra’ or problematic Head No.10 (we will call him ‘H10’) is non-conformist and longs for the “simple pleasure” of think independently, and for freedom in general from the collective of the other nine heads (‘H1-9’); the latter are a group, always aggressive and looking for world domination, enchanted by the potential of Kubera’s flying machine – as if it were an F-16 or a drone; H10 is pondering higher thoughts. We learn that H1-9 have taken up the navarasas or the ‘nine universal human sentiments.’ H10 is now bereft of both a featured ‘rasa’ or emotion and a physical place, and is thus, a zero, a non-face. Unsurprisingly, but alas, H10 is the one who falls truly in love with Sita. “Not a word, just a look; I saw her eyes!” he says plaintively. In a memorable movement sequence, Vinay’s body exquisitely arcs and torques in slow motion against a Dhrupad alap, as love and desire course through H10. Later, when H1-9 say, “Let’s kill her!” H10 counters chivalrously: “But she dances, sings, knows mathematics….!” A group of artists, commissioned by H10 to find a solution or his freedom, fail. A-ha! An idea: a spacing and sizing adjustment is needed for the heads, all ten of them, to fit on Ravana’s torso. In comes a fantastic resizing machine (on the screen),complete with ‘enhancer’ and ‘diminisher’ programme buttons. A few heads are stretched sideways, another couple or so shrunk, and thus finally, the tenth sits centre with four others on one side and five shrunken ones on the other, occupying equal total space on either side. Solved! This writer will not be able to see Ravana again without looking for this balanced re-sizing or imbalance! The opening ‘Glimpsing Sita’ section, performed in silence, signals the contemporary genre with a view of a muscled shoulder, then a partially seen face, then a whole head that sees and withdraws only to re-emerge in a phased build-up of the effect of ‘the sighting of Sita.’ The sequence with Vinay seated on a box Kathakali/Koodiyattam style, wherein H10 ‘puts on’, at Sita’s behest, various other ‘heads’ with their navarasa expressions was masterful, and clever in its exchange with the superb drummers/musicians (Nimmy Raphel, Suresh Kaliyath, Arvind Rane). Nimmy plays superbly and non-stop on the mizhavu drum for a good half-hour for this section, as Arvind sustains with the edakka drum. In addition to Adishakti’s signature live drumming, the music, part recorded draws from a vast range from eastern and western classical and popular genres, provide layers if not always a good fit, as music genres and compositions have their own baggage and burden from the cultures that produced them. Likewise, it is not clear that all the animation and projections, while interesting conceptually, work to advance or deepen the telling, all the time. In the post-performance Q & A, Vinay said this work was a part of Adishakti’s three-year Ramayana project under the guidance of Veenapani Chawla, wherein each of the main company actors were charged with writing and making their own work. It took him six months to alight on a topic, given the vastness of the epic. It was a series of paintings of Ravana created over centuries, he said, that grabbed his attention because visual artists appeared to have struggled with various combinations and permutations to symmetrically place Ravana’s ten heads, from pyramids to laterals and other formations, but in a sustainable fashion given the pull of gravity on total mass! Yet, we may ask, where is Ravana among all these various heads? Providing a totally different take from usual interpretations, the question still reverberates after the show finishes, leaving a marked trace.

Hari Krishnan, Nimmy Raphel Nimmy Raphael’s ‘Nidravathvam’ continued the exploration the following evening. Her first ever venture into playwriting makes up a new tale for two brothers from the Ramayana, the brothers of the hero Rama and anti-hero Ravana, Lakshmana and Kumbakarna, respectively, an encounter that is entirely fantastical. Ravana’s brother Kumbakarna’s cyclical sleeping and eating routines are problematic and a matter for existential angst as Kumbakarna cannot help his brother in war if he is overcome by sleep or relentless hunger. This long sleep cycle of half-a-year followed by half-year’s feeding frenzy is the result of a misspoken request for a boon, which story is present in the epic: instead of asking for nirdevathvam or annihilation of the devas, he asks for nidravathvam or sleep – because the goddess Saraswati scrambles his speech. Then there’s the lesser-known ‘fact’ of Lakshmana’s boon of wakeful vigil during the fourteen years of exile. He too is existentially troubled. How will he make up for his sleepless years? His boon did not specify. (“Will she be awake when I am asleep?” wonders Lakshmana about his wife left behind, and we feel truly sorry for him.) With a clever twist of writing, Lakshmana becomes the narrator of Kumbakarna’s tale of woe. The latter begs Lakshmana to take on some of his sleep so he may stay awake long enough to kill him – and so do his brotherly duty to Ravana. Lakshmana agrees and his meditations take a deeply philosophical turn, but then Kumbakarna is killed before the sleep transfers. Death intervenes to resolve the situation. But before that happens, the telling of “Kumbi” is hilarious, riotous even, as Kumbakarna is accompanied by a feisty fly, his adventurous ‘secretary’ named Mrs. Kutty, who likes her “Martinis dry to fly high”! The scene where the two of them ‘fly’ is thrillingly conveyed by Nimmy squatting deeply in muzhumandi on a black box, her arms (as Kumbi) ploughing through the air, head and shoulders moving aerodynamically. The deep mandala positions may come from Mohiniattam but they are altered and grounded; the awesome balance and strength in leg lifts and holds speak undoubtedly to Nimmy’s long Kalari training; but from practice as surely comes the impressive multi-tasking skill of juggling as she speaks her humour-filled lines and kicks a leg for emphasis, unerringly on all three fronts. In fact, Nimmy’s physicality is so superbly assured – not “hyper masculine” a term that came up a lot in the rest of the Purush conference that followed – that this writer did not stop to think that she was playing male characters. Dressed in a lungi and camisole top, Nimmy’s theatrical presence and commitment was complete enough to be transformative during the full evening’s work, which had lighting, music support from the Adishakti team. For this writer, Nidravathvam, a debut play, was the more directly engaging in the small venue as the actor’s space was undisturbed by digital or other interventions. Adishakti founder-artistic director and creative advisor for the two plays Veenapani Chawla said in the Q & A that “myths are a body of knowledge in seed form that need to be unravelled and [thus] honoured.” In this context, both works honour the myth even as they entertain different ideas, and engage us as spectators.We understand that there is a third play by another member Arvind Rane, which we did not get to see but that completes Adishakti’s Ramayana triptych. Chitra Sundaram is a Bharatanatyam dancer based in London. A choreographer, performer and commentator, Chitra Sundaram also serves on private and public organisations in advisory and trustee capacities. |