|   |

|   |

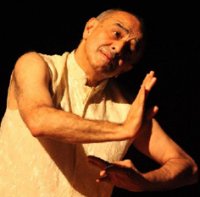

Context, Collaboration and Commerce - Lalitha Venkat e-mail: lalvenkat@yahoo.com September 24, 2013 In continuance with the Prakriti Excellence in Contemporary Dance Awards (PECDA), Prakriti Foundation hosted a two day round table/discussion on contemporary dance on the 30th and 31st of August 2013 at the Goethe Institut, Chennai from 11am to 5pm. It brought together performers, dance critics, producers and others to discuss the broader frame of ‘Context, Collaboration and Commerce.’ The aim was to provide a common platform for the performers to strengthen their existing networks, discuss their issues and outline the possible actions to support the contemporary dance community on the above subjects in India. About 25 to 30 people attended the discussion on both days. Having worked with Ranjabati Sircar, Aishika Chakraborty (Associate Professor, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur Uni, Kolkata) spoke with reference to her works as well as contemporary dance in Bengal. For Ranjabati, contemporary was not a style, it was a way of thinking, a thinking body and a moving mind. In the 1980s, contemporary work made its mark in India with dancers like Mrinalini Sarabhai, Chandralekha and Ranjabati, who “wrote their autobiographies in their choreographies, removing the plastic smile and de-cluttering the costumes.” Ranjabati changed the face of Bengali contemporary dance. Tagore provided the context of respectable middle class women performing on stage to an unfamiliar audience. He questioned the classicism upheld by Natya Shastra, took Baul and garba with Kathakali and Manipuri. He asked Ruth St Denis to join the faculty of Vishwabarathi but she was not able to. Tagore wrote and directed Natir Puja (1931/32) or ‘Worship of the dancer,’ the only film that he also acted in. In Uday Shankar’s choreographies, dance always centred around him. Manjushri Chaki-Sircar was considered too tall to be a part of Uday Shankar’s chorus and hence was turned down. Manjushri was criticized for grafting alien movements on the Indian body. Aishika ended by saying no one can ever predict what changes will take place in contemporary dance, what it will become in the future.  “Dance has been my life, my expression” - Astad Deboo, called the father of modern Indian Contemporary dance, spoke in story telling fashion about how his adventurous spirit took him around the world and in touch with various styles of dance. He saw dance as a child in Kolkata and was attracted. From the age of 8 to 16, he learnt Kathak from Guru Prahlad Das in Jamshedpur. After completing school, Astad wanted to learn acting too and went to Mumbai to do commerce and economics, performing in college programs. Seeing Murray Louis Dance Company opened his eyes to group performances, how to work using space and light. Uttara Asha Coolawala, who was then studying the Martha Graham technique, offered to help him with the ‘I 20’ formalities for study in the US for which he had the full support of his parents. Astad decided to hitchhike in Europe and explore. He sailed out, got off at Iran, travelled through Turkey, Europe and reached London where the Martha Graham technique was being taught at the London School of Contemporary Dance. He taught Kathak to survive. From there, he went to Canada (those days, visa was on arrival). “I would contact student unions, offer my little act, try to take classes, and have dialogues with dance companies.” From Canada, he went to Japan to observe kabuki, rather difficult since the masters were not open, but he “managed” by becoming a ramp model and English teacher. His presentations were based then on Kathak. “I then went to Korea, Papua New Guinea where I got robbed and was left with just my ticket. In Hong Kong, I did odd jobs, taught dance and made good my loss. Apart from dance, I was very adventurous and went to Vietnam and Thailand. I was a gofer boy for a photographer, carrying his equipment during the Vietnam War. My journey took me to Indonesia and Australia where I auditioned for a role in Sydney and got it. After starting in 1969, I made it to US only in 1974.” In New York, Astad took Jose Limon classes but had to leave every 6 months to renew his visa. After visiting Africa, South America and Mexico, he returned to India only in 1977. When scholar / critic Dr. Sunil Kothari saw Astad perform with St Xavier’s college students, he had suggested that Astad learn Kathakali. “I was that time still fumbling through my moves, searching for my dance vocabulary.” For 3 years, he had a great guru-shishya relationship with his Kathakali guru under whose guidance, he added to his dance vocabulary. When Pina Bausch invited him to join as apprentice, he went to Wuppertal in 1980. “Pina had lost her partner and was in no mood. She wanted me to do Indian way of dance but that wasn’t what I wanted. It did not work out, but she let me take classes and observe her productions. After that I decided to make India my base but had to face rejection from sponsors and the government. That did not deter me. Many Indian classical musicians were open about collaborating with me. I encountered the Gundecha Brothers in Bhopal and responded to their singing. I got an opportunity to perform at Khajuraho Festival. I collaborated with Dadi Padamjee for 6 to 7 years. I worked with Kolkata’s deaf theatre company Action Players and Zarine Chowdhry. It was thanks to Max Mueller Bhavan that kept me going. I had a good honeymoon till ladies started heading MMB. Along with my work with the deaf, I presented solos around the world. My cousin introduced me to the head of performing arts at Gallaudet University in Washington DC, and my work with them lasted 10 years. I was able to take my Kolkata deaf group there for summer camps. The girls at the Clarke School for the Deaf (Chennai) were trained in Bharatanatyam and I created a full length piece Contraposition for them. We even opened the Deaf Olympics in Australia. This collaboration lasted 7 years. With the Manipuri thang-tha artistes with whom I did ‘Celebrations,’ I worked for 10 years and then found a pung cholom guru with whom I still work. I was invited by Salaam Balak Trust (Delhi) to work with them and we did ‘Breaking Boundaries.’ I then revisited my solo work ‘Interpreting Tagore’ and made it a group work with them.” This work is presently receiving rave reviews wherever it is being presented. As Astad himself admitted, he refrained from sob stories about the difficulties in getting sponsorships for contemporary work. Devina Dutt, an arts writer based in Mumbai, wondered if there is an Indian way of contemporary dancing and how does it change from time and time. Amid corporate shows and Bollywood shows, contemporary dancers have to develop their own context and space. Two dance companies have moved from Delhi to Mumbai to choreograph for films. She observed that the best response for UK based Akram Khan’s work came from France. With the help of short video clips, Devina centered her presentation on Kathak dancer Sanjukta Wagh who “never frets over grants, performance opportunities or making too many productions.” Wagh is not performance hungry but is after process. When she tried to break down the text in a Kathak sammelan in Pune, she did not get a favorable reaction as they were looking for literal translation into dance. In her first 9 months at Laban, Wagh had to unlearn her classical technique. After her Laban experience, she has taken a classical piece and made it contemporary and vice versa, playing around with notations. Devina said, “It is disturbing that some young dancers invoke the freedom of contemporary dance without understanding the connotations producing average works and we must learn to reject such works. There’s no critiquing nowadays which is also disturbing.” Given below are some points made by the participants during the course of discussion in the afternoon session. In a paper sent via email, scholar Saskia Kersenboom mentioned that dance progressed from local to translocal form to contemporary to decontextualised Indian dance. There is dominance of the classical in dance and print culture. Dance and music were both codified around the same time and is not older than the 20th century in south India. Anmol Vellani (Founder-Director, India Foundation for the Arts, Bangalore): “Out of the research tradition, we have the documentation. Contemporary dance rejects anything that came before. There’s a danger of connectivity becoming dumbed down.” Jayachandran Pallazhy (Artistic Director of Attakkalari, Bangalore): “There are different ways of accessing institutional resources. Critiquing and evaluation process should be in envisioning to give a sense of direction. Young people have lots of view points and we should help in channelizing them in the right direction.”

Padmini Chettur (Chennai based contemporary dancer): “The way we say ‘institution’ now is different from how it was used in reference to Kalakshetra. There is immense confusion because people do not know how to process. I see 10 movements in 90% of the performances I have been going to, ending in kitchdi. Contemporary dance is an evolution of technique, not mixing of techniques.” Sadanand Menon (Arts editor, arts curator and writer, Chennai): “Who is the work for? If you say ‘audience,’ you will need institution, the market takes over. Market demands increase in so many spheres. If we address an issue, it creates the work.” Day two featured discussion over problem of space for rehearsals, high cost of tech heavy productions, dearth of performance opportunities as well as bias by some venues not to feature contemporary dances, lack of audience and the commerce aspect. Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy of Kha Foundation, Bangalore, said prime problem for them was studio space. Renting space for rehearsals involves exorbitant rates and they have even rehearsed in parks. He gave it a shot and requested ‘A1000yoga’ to lend them their space when it was not being used, for rehearsing his latest work ‘NH7’ at a nominal rate and in return, he would give them publicity. It worked and they had 3 months of stress free rehearsals. Deepak feels people are generous if you persist. Delhi based contemporary dancer Mandeep Raiky thinks “letting someone else into your rehearsal space is a positive outcome.” Contemporary dance productions rely heavily on tech and this was discussed at length. “For international standing, it requires 3 to 4 tech rehearsals at the venue. Foreign technicians could be racist when dealing with Indian artistes. I give option of 2 days or even 2 hours of tech as I did recently in Odisha,” said Padmini Chettur. Anita Ratnam mentioned that Aditi Mangaldas has hired tech directors from Akram Khan’s team to launch her as an international brand and their demand was for her to provide 4 days of tech for the premiere of ‘Within’ that took place recently. Naturally this involves a lot of money and something not many in India can afford. Some responses include: Sadanand Menon: “Dependence on technology is a complete fetish. Of course, costs are huge. We don’t need to aspire to that to fit into the international circle. Without all this, Chandralekha had a fairly international presence. Does one need masala or sensationalism to bring in an audience? If the work does not speak to the audience, there is no point in performing it. Premise has to be the content of the work, tech requirements can come later. One can get locked in that fetish as they feel that’s what will bring the crowds.” Jayachandran: “Not everyone will be in tune with what you are doing. A smaller number will identify with your vision. Reaching out to youngsters is important. It’s not about the complexity of technology but how to use the technology. Commercially, hiring a big theatre is non-viable. You could use a smaller space.” Mandeep Raikhy: “The way the body is viewed is the way light falls on it. It is very important and I would not compromise on it.” Anmol Vellani: “If tech is very important in your work, why not work with it from the beginning? The reason why many work only a few days before the performance with tech is because of economic constraints.” Jyoti Dogra (actress from Mumbai): “Even if you have the money, it is too nerve wracking if dependency is on tech for a production. Lots can go wrong and not work in the same way for the next performance. For certain people’s work, a certain number of people come, regardless of quality, in order to support the artiste and not necessarily enjoy his/her work.” Ranvir Shah: “If the work is not good or strong enough, it will not work whether the tech is great or not.” Devina Dutt: “One does not need family and friends but people from outside your circle to see your work.” The point of discussion then moved to the commerce aspect. Arts organizations are like micro economies. In a taped video footage, UK based producer Farooq Chowdhry spoke about how they had managed to market Akram Khan as a brand, how they make money through touring doing 150 shows a year. “People are afraid to invest in the arts and artistes as a waste of time and faith.” If you change the way people feel, your aim is realized. “Marketing or branding a performance is not the point. It should be about building the reputation of the institution. Building relationships is a slow process for people to become friends and help each other with resources,” said Anmol Vellani. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Bureaucrat / dancer from Hyderabad) suggests that dance has to be supported by some other training. An alternative extra training and knowledge is important for a dancer to sustain. The return on investment in dance is nil for the first 15 years. One can hang on only if something else like light design, nattuvangam skills etc is there to survive. Padmini Chettur feels the western model is working better than the Indian model. When she said the IFA (India Foundation for the Arts) turned down her application saying they don’t support non-Indian artistes, she wondered how she could in any way be considered non-Indian. Anmol Vellani was quick to point out that “IFA does not support international collaborations” and her application was turned down because of foreign collaborators involved. Someone quoted Philip Glass, “The hardest thing for an artiste is not to find his voice but to lose it.” There are lots of dancers in Bangalore, and talk of branding deters creativity, said Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy, who feels it would be nice if dancers can create, make mistakes and recreate which is where mentoring would help the dancers. Since dancers need space, mentoring and venues, Ranvir Shah suggested that sometimes if audience cannot go to the venues, why not take your work to the audience like universities, corporates etc. Jayachandran’s idea is to create a grid of dance productions and spaces that could be used by artistes to help each other. Two papers sent by artist Natesh and dancer Preeti Athreya was read out by Ranvir Shah. The main point made by Natesh was, “I’m more of a collaborator than a light designer. As a painter my need to spend hours before a canvas got transferred to dance. The number of rehearsals I am at for any production is more than what light designers require to design a piece. During this process of internalizing, I move with the mood of the dancer like a co-actor. So collaboration is an automatic act.” Excerpts from Preeti’s works ‘Porcelain’ and ‘Lights don’t have arms to carry us’ were screened. The gist of her paper could be summed up as: “One of the foremost things about collaborations that strike me as pertinent is the genuine desire and curiosity between artistes to actually access the other’s world. The project becomes a way to do this. It also means that you feel a sense of location in some kind of shared phenomena, even before the idea of a creation comes into the picture. I do realize that this kind of collaborative work is more and more difficult to find given the artistic/economic environment that is fast developing and attempting to evaluate work. In the case of the independent arts scene (which pretty much describes most of the artistes today), an artist driven collaboration requires enormous drive and persistence to carry the process to its natural conclusion, whether or not this means performance. The complications that arise have to do with the fact that conditions of work and professional commitment vary from one artist to another and from one country to another. This has its impact on the time and focus of the artistes involved.” Mandeep Raiky feels the need to collaborate. Through mistakes, you should learn to choose your collaborator, one with similar sense of play, compatibility of aesthetics, collaboration in sense of how and spirit and not what. The collaborator should be someone who excites you. One can bring in the right people to be the outside eyes. It is easy to move but to question how you move is the challenge. Spirit of collaboration is like loosening of nuts and bolts in your body. “If nothing changes in the way I see my form, it’s no use. It should be a bit of me and my collaborator and a third form arises.” For Jayachandran, collaborative process is different for each artiste. “It gives a framework and forces you to go out of your set path. We arrive at the ideas we want to explore, a rough kind of story board, the strategies and then the artistic exploration begins. You meet your collaborator half way, then refine and transform the process between different artistes. Each collaborative process involves different strategies. As a choreographer, sometimes it is good to be outside the piece.” Deepak said he inserts himself into the group work only if he feels it is necessary and a different body would not suit the existing group. A general summing up was done about the points to be attended to, to make life easier for the artistes. A suggestion was to contact the finance ministry to ask for allocation for the arts. Media persons could work with the dancers to bring out this issue in the media. There should be writing on art and culture. A workable, doable, viable framework should be arrived at and so on. Ultimately, the success of a dance seminar will reflect only in the implementation of the points and strategies discussed. Lalitha Venkat is the content editor of www.narthaki.com |