|   |

|   |

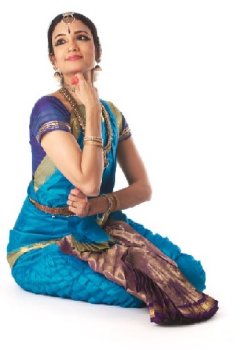

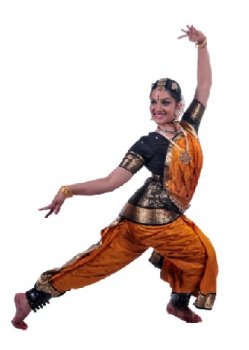

Gait to the spirit - Anil Raj e-mail: ilpint@hotmail.com November 18, 2012 At the conclusion of the third annual iteration of the ‘Gait to the Spirit’ Festival of Indian Classical Dance presented by Mandala Arts Society and its founder Jai Govinda, Vancouver dance lovers were as replete as banquet guests at the end of a feast. Little surprise, considering the menu presented for our cultural degustation: three different Indian classical dance forms exquisitely presented by three artistes of international renown, two of whom went on to present a lecture demo and a master class, and a beautiful recital by an emerging local artiste, choreographed by Jai Govinda himself. Our city has profited immensely from Montrealer Jai Govinda’s decision to move out West some twenty years ago. His dedication to his chosen art form Bharatanatyam - as teacher and choreographer - has resulted in a generation of dancers performing their arangetrams (debut professional recitals – a graduation ceremony, if you will) and going on to achieve more both here and internationally. Through the Gait to the Spirit Festival, he has brought the foremost exponents of Bharatanatyam to Vancouver, and this year, the festival presented a combination of Indian classical dance forms rarely seen together - Odissi, Kathak and Bharatanatyam. Jai Govinda should also be commended for educating audiences. He raises our standards; he teaches us to become more fastidious in our appreciation by introducing us to talents that have stood the test of the world arena. This is what is possible; he appears to be telling us, both students and audiences - this is what is achievable, if you are committed and hard-working.  Gait to the Spirit’s first evening began on a high note with California based Shalini Patnaik’s three-part Odissi program: Pancha Bhuta, an invocatory piece in praise of the elements Earth, Water, Fire, Wind, and Sky which together create and sustain all life. Shalini gracefully enacted each of the elements as the lyrics extolled the gifts each one bestows upon all creation. She followed this piece with one in praise of Ardhanareeshwar, the incarnation of Shiva that embodies both male and female. A joy to watch, as she effectively portrayed the masculinity of Shiva, smeared with ashes, bedecked with serpents, his matted hair crowned with the crescent moon and cooled by the Ganges, as he vigorously dances the taandav. Then before our eyes, she transformed into Parvati, his divine consort, voluptuous and feminine, nurturing mother goddess and celestial wife. Odissi’s hallmarks – the strong base and fluid upper body – came into full play in her final piece, Kirwani Pallavi. Based on raag Kirwani, the pallavi was a celebration of pure dance. One could appreciate the conjoining of motion, musculature, breathing and foot work as they worked in concert to express something as ineffable as emotion. At her young age, Shalini has already collaborated with established talents like Madonna, Ricky Martin, and Anoushka Shankar, and it was very evident that many more laurels lie in her future. The second half of the evening’s shared bill was Vancouver’s introduction to UK dance phenomenon Aakash Odedra. Although Aakash has spent the past year with a world tour of ‘Rising,’ wherein three contemporary choreographers each contribute a solo piece “using Aakash’s body as instrument…in turn allowing him to observe the creative processes of three very distinct choreographers,” his Gait to the Spirit appearance marked a rare return to his Kathak roots. His opener “Jiya” was a heartbreakingly evocative piece from the tawaif repertory. Tawaifs or courtesans were the foremost exponents of Kathak until they sank into obscurity, sad victims of Victorian prudery: the British viewed nautch girls as erotically vagrant and corrupters of public morals. The dancer’s joy at being reunited with her lover, and her devastation upon being abandoned were palpable in Aakash’s telling of the tawaif’s tragic story. “Jiya” featured the poetry of “Badi” Malik Jaan, a famous tawaif of the 19th century. This was followed by a piece of nritta or pure dance, which allow a dancer to showcase virtuosity and footwork. Aakash’s athleticism, boundless energy, and seeming imperviousness to the laws of gravity came to the forefront in this piece, which while maintaining the integrity of Kathak, included subtle nods to other world dance forms. The merest stretch of imagination allowed one to see where Kathak could lead to Flamenco, or the hearty folkdances of the Steppes, or the vaulting leaps of European ballet. A Meera bhajan “Barse Badariya” was next on his program. The mystic princess Meera ecstatically dances at the arrival of the rains for they augur the return of her divine lover Krishna. This piece allowed for abhinaya or emotive expressiveness as the dancer depicts the rains pelting down on Meera’s face turned heaven-ward, as she eagerly awaits the arrival of her Lord. We watched a short interstitial black-and-white video of Aakash’s contemporary dance work, while he swiftly changed costume for his final piece, a sublime piece of Sufi Kathak to the Amir Khusro composition, “Mohe apne hi rang mein”. Here the dancer, clad simply in a voluminous white tunic, combined the turns of a Sufi dervish with the intricate footwork of Kathak. The tunic took on a life of its own as the dancer whipped himself into a state of divine ecstasy – it spun outspread, as if aspiring to flight, while the dancer invoked the Master Dyer and begged for a single drop of divine dye sufficient to colour his entire existence. This was no longer a dance performance but a transcendent act of worship – after a moment of stunned silence when it ended, the audience broke into wild applause and gave Aakash Odedra a standing ovation.  The second evening belonged to festival headliner Savitha Sastry. I don’t use the term “belong” lightly – Savitha Sastry took complete ownership of the evening through her masterful interpretations of the Bharatanatyam dance form. A couple of departures from tradition added her piquant individual stamp: she started the evening in a splendid costume made of, not the traditional Kanchipuram silk, but a fine gold and burnt orange Pochampally ikat, infusing a little bit of Andhra Pradesh into the dance form of Tamil Nadu. In another non-traditional touch, she chose a composition in Avadhi braj bhasha (a colloquial dialect of Hindustani), Mat Roko Dagar, instead of classical Tamil, as she enacted the divine romance of Radha and Krishna. Savitha Sastry possesses that rare combination of stunning beauty, confident artistry, well-honed craft and emotive talent. Her opening invocation piece was to verses by the South Indian saint Adi Shankara. All Indian classical dance forms came into being as part of religious ritual, so spirituality is an inseparable element. The common thread through the separate dance forms we witnessed was this profound expression of the spiritual through the art of dance. Savitha then performed a Pada Varnam, an exacting union of dance technique, footwork, and superior abhinaya, as she played a lovelorn maiden entreating her flute-playing Lord Krishna to recognize her deep love for him. Interspersing dance sections of breathtaking beauty and rapid footwork with expository segments wherein the naayika (heroine) questions her lord in anguish, “Isn’t my love for you greater than the devotion expressed by others?” Savitha conveyed the pain of the maiden whose divine lover appears not to reciprocate her passion. In her expression of shringaar rasa (sensual love), we witnessed not some girlish crush, but the profound pain and longing of a mature woman unsure of her man. It was fascinating to watch the play of emotions flit across her expressive features and the degree of transparency she wrought to allow the audience to view her heartbreak. We were truly privileged to witness artistry on such a scale. Her next piece extolled love of a different sort. Using the verses of an enlightened Tamil poet who most unusually sang the praises of the girl child over a hundred years ago in a culture known for its firmly entrenched patriarchy, Savitha embodied vaatsalya or maternal love as she watched her little daughter frolic and play. Again, Savitha’s marvelous acting ability allowed us to see a toddler who has only just learned to walk, and the pride and joy with which her mother watches her. She followed her ode to the girl child, with an enactment of the divine lovers Radha and Krishna as, for the first time, they declare their love for each other. This was performed to the song “Mat Roko Dagar” – audiences are accustomed to watching Bharatanatyam danced to Carnatic music with Tamil lyrics – it was a treat to hear lyrics in Braj Bhasha, which is familiar to North Indian audiences. In no way did it compromise the purity of the dance; in fact, it enhanced the viewer’s comprehension and made it completely accessible. Savitha’s finale was the Thillana, with which a dancer traditionally concludes her recital. This was her piece-de-resistance, entailing rapid steps, footwork of dazzling complexity, coupled with beautiful emotive passages showering praise on the sacred butter thief Krishna, preserver of the world and remover of earthly suffering. The recital brought the audience to its feet. As one, they gave Savitha a richly merited standing ovation – applause that would not abate even as she acknowledged it with graceful humility.  Mandala Arts offers its stellar pupils a professional platform through its Emerging Artiste program, and this year’s Gait to the Spirit Festival closer was a scintillating performance by young Malavika Santhosh. Local audiences have watched the blossoming of this dancer with great delight, and she did us all proud with her enthusiastic participation in her alma mater’s annual festival. In pieces specifically choreographed for her by her guru Jai Govinda, Malavika danced in praise of three goddesses of the Hindu pantheon. Her opening Pushpanjali sought the blessings of Saraswati, goddess of knowledge and patroness of the fine arts, which segued into a complex varnam in praise of Durga the Mother Goddess and destroyer of the demon Mahishasura. Malavika prefaced this piece with an explanation and demonstrated some of the mudras she would be using. This made audience members who have seen Malavika’s progress burst with pride – how far this child has come! One hopes that she will continue on with her exploration of the glorious tradition of Bharatanatyam and carve a niche for herself with her interpretations. Lakshmi the goddess of abundance was next to receive obeisance as Malavika extolled her attributes and danced in her praise. Her Thillana in raag Dhanashri was for the glory of Krishna, rejoicing in the sound of the ghungroos (ankle bells) of the divine One and his cohorts dancing in merriment in the parks of Vrindavan. Congratulations to Malavika, her guru, and her parents on achieving another milestone in the journey of an artiste. Breaking bread with the visiting artistes of the Festival gave one a unique perspective – one saw the human aspect of the dedicated performer, and their individual personalities came through loud and clear. It was interesting to note the points of intersection and divergence: all three of the visiting performers recognized early on the inevitability of their vocation. Savitha began her dance education in Mumbai from a very young age. From the time she was a little girl, she sweet-talked her way to front row seats at every dance recital at the city’s famous performance venue Shanmukhananda Hall, which adjoined her family home. Even as a five year old, she couldn’t wait to see the costume changes (dancers traditionally change into a fresh costume during the intermission). Overcoming family objections, she made dance her vocation. (South Indians in major urban areas are tolerant of dance as long as it remains a hobby – as a vocation it becomes dangerous, for it diminishes one’s perceived suitability as a prospective bride.) Happily, she found a spouse who has been extremely supportive of her artistic endeavours. Savitha is in the fortunate situation of being able to pursue her dance career and ambitions independently of grant making bodies in the USA and India. She recently shifted residence to New Delhi to further her dance interests and has done so without resorting to external funding. The jaw-dropper is that she has an eighteen year old son, who is a budding photographer – the stunning photographs on her website are by him. Aakash recounts how he walked on tip-toe as an infant learning to walk, causing his relatives to comment that the child was destined to be a dancer. Despite the fact that dance was not an obvious career choice for boy children from his conservative Kathiawadi business community, Aakash benefited from his parents’ hands-off approach to child-rearing. When he announced his vocational choice, he encountered no opposition. This policy of non-interference was probably the best they could have followed, for young Aaakash was able to study dance in a guilt-free environment. Dance was pre-ordained for Shalini because she was born into a family steeped in the study and propagation of the Odissi dance form. Her mother Gopa was a dancer and inculcated all three of her daughters (Shalini is the youngest) in the art form. The family-run Odissi dance academy ensured teachers of high calibre, and any gaps in instruction were filled by renowned Odissi teachers in India. The family spent every summer vacation in India, where all three Patnaik daughters received rigorous dance instruction. Aakash says he identifies with the tawaifs because, like them, he lost out on a “normal” life due to his dedication to dance. Is there a note of wistfulness at the thought of what might have been had he not been in the thrall of dance? Perhaps, but there is so much joy and fulfillment in giving oneself up to dance and so much to be achieved. Certainly one has subsumed oneself for one’s art, but the results - as the audience will attest - are nothing short of brilliant. And so, as long as the music plays and the ghungroos are tied on their ankles, these dancers will dance. They dance to perpetuate an ancient heritage – they seek to redefine age-old art forms for a contemporary generation – but, quite simply, they dance because they must. It is junoon – obsession – and we, the audience, benefit from their divine madness. God bless each one in their pursuit of excellence; may the music never stop for them. And congratulations to Jai Govinda and his team at Mandala Arts for successfully staging another Gait to the Spirit Festival. Anil Raj is a Vancouver-based writer, producer, performer, film critic, and self-confessed dance junkie. |