|   |

|   |

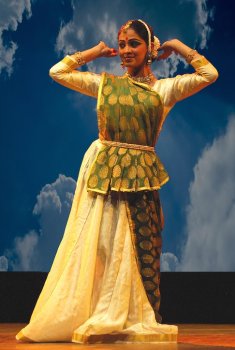

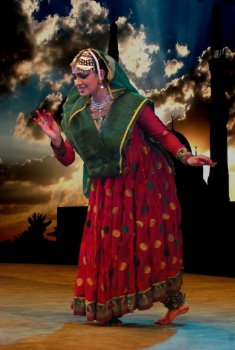

Kathak heralded the monsoon season - Chittaranjan Mothikhane e-mail: chittaranjanmothikhane@gmail.com June 22, 2012 Shivapriya presented its 3rd annual dance festival NRITYANTARA from June 18 to 20 in Bangalore. The festival spread over three days was spread across the city too, benefitting rasikas to witness at least one evening of classical dances closest to their area. The second day was at the ADA Rangamandira. It’s here that one saw a showcase of two classical styles and a group choreography. Shweta Venkatesh presented Kathak in four segments that explored the different stages of Kathak in its evolution. The artistic and political perspective well narrated by Guru Mysore B Nagaraj, under whom the artiste trains in this classical dance form of North India described the metamorphosis of the art form from what was an art of story tellers in the village gatherings to the present scenario of an Islamic touch to a Hindu art. The background was aptly illuminated with projected imagery that was appropriate to the stages that Kathak went through. As an example of Kathak that was an act of worship in the temples, Shweta offered obeisance to Goddess Saraswathi. This raag Yaman based musical rendition of traditional Sanskrit shloka sans any rhythm invoked the Goddess as the dancer unfolded the meaning of the verse through understandable hand gestures and subtle feelings. Kathak in its third stage of evolution found patronage in the court halls of the Hindu kings. What was essentially a spiritual art, the dancers embellished their acts with appropriate technical dancing for entertainment. The complicated syllables of the percussion instrument were translated to movement that was fast, mercurial and geometrical. This tritaal rendition was a perfect example of the nritta aspect of Kathak in the Hindu courts. Shweta Venkatesh went through selected compositions of the Sitarkhani style of rhythm patterns that gave us a glimpse of dance in the royal courts of Jaipur.  The Hindu format  The Mughal format It was during the Islamic rule that the Persian influence was seen in Kathak dancing. The more tolerant rulers allowed the Kathakars to remove the spiritual content in their compositions and bring in the emotional gamut that humans go through in their lives. Compositions of ghazals, thumris, tappas were danced to. Shweta chose a Kajari, a composition that expresses the pain of separation from her beloved during the monsoon. The artiste’s subtle abhinaya made the audience feel the pain that the character experienced during the season. Her request to the clouds not to shed rain in her courtyard, pleading with the koel to stop singing and the peacock dancing was communicative of the essence of the lyrics. The message that the nayika sent written on the vapors, so it can carry to her beloved along with the clouds was touching. The poetry of Sada Ambalvi, a famous Urdu and Punjabi poet of India, was set to raag Miyan Ki Malhar. As an example of the fourth stage, Kathak in the durbars of the Muslim kings in Awadh, the erstwhile Lucknow, Shweta concluded her recital with a Tarana. The dance languorously performed gave us a glimpse of the leisurely life style of the era. The transformation of the movements that were originally Hindu now modified to the sensibilities of the Islamic rulers was recognizable. The concluding footwork was electrifying as the cadence of the ankle bells created an audio imagery while befittingly replying to the challenges put forth by the percussionist. The Malhar raag composition heralded the arrival of the monsoon in Bangalore. The next day was the beginning of a new season “Aashad.” |