It’s story time: Natyarangam’s Bharatham Kathai Kathaiyaam (Part 2)

Text & pics: Lalitha Venkat, Chennai

e-mail: lalvenkat@yahoo.com

August 24, 2011

Aug 15

The evening started out interestingly. I asked the auto driver, how much

to Narada Gana Sabha? He replied in English, “Three zero.” I said, “No.

Two five.” The deal was struck, a war was averted! But war was the

theme of Chitra Chandrasekhar Dasarathy’s presentations. The story of

‘Sooriyan’ by Ambai was read out by Dr. Thirupur Krishnan. It is war

time and innocent civilian lives are claimed by cruel enemies. The

protagonists are dwellers underground. The mother and her five-year-old

son, who has never seen daylight, walk in darkness on the battlefield to

check the fate of his sister who is missing, at the end of which they

find she is dead and by then the morning rays of the sun break out.

Music was by her father Guru CV Chandrasekhar. Chitra’s abhinaya was

remarkable. She enacted pathos so beautifully that in a couple of

instances, she was so into her character, we literally saw her lips

tremble and her eyes swim in tears.

War has many faces. The parallel story was of King Asoka and the battle

of Kalinga titled ‘Raktamallika' or the ‘Red Jasmine.' Ashoka wins the

war but is he really happy with his victories? Why is the old lady

sitting on the battlefield? Does she not have a son? He has reached god.

Ashoka walks on. Why are the flowers in the garden red? The river is a

ribbon of blood, so the garden now has red jasmine instead of white. He

sees his army running riot, there’s bloodshed everywhere. Has his rage

for victory resulted in this? He is confused. Ashoka gives up war and

goes in search of truth and peace. Chitra drew on Jai Shankar Prasad’s

Ashoka Chinta and Kannada work Priyadarshi Ashoka by Masthi Venkatesa

Iyengar for this item.

Chitra’s challenge was in “trying to portray death and pathos, and

widespread effects of violence in an aesthetic manner without being

depressive. My interest in literature and earlier work in theatre helped

me in exploring the varied ways violence affects the mother and the

child in Ambai's story and King Asoka.” Be it the mother’s tears of the

first story or Ashoka’s despair at the ravages of war, Chitra lived the

emotions. The orchestra comprised of vocalist Nanda Kumar, who modulated

his voice to very soft for scenes of pathos, Praveen Kumar on

nattuvangam, Mysore R Dayakar on violin and Gurumurthy on mridangam.

|

Chitra Chandrasekhar Dasarathy

|

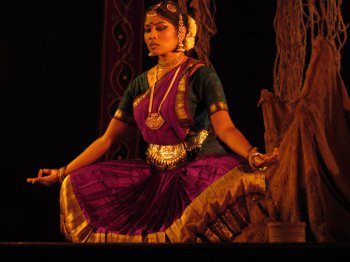

Vidhya Subramanian

|

Definition of godliness was the theme for US based dancer Vidhya

Subramanian, who presented ‘Namavali’ by R Choodamani. The story that

was published in 1992 was read out by K Bharati, a close associate of

the author. In this story, the Almighty is the narrator, and it’s about

how he is present where there is fairness and justice. Kanakarasan and

his brother Arunagiri do business separately, but while the former is a

failure, the latter flourishes. Kanakarasan ends up working in a small

company to keep his family of 4 alive. He suddenly develops stomach pain

and this necessitates an operation costing Rs.30,000. He mortgages his

house to his brother. The operation is done but he does not survive. His

wife Shenbagam is unable to return the money, so Arunagiri offers her

another Rs.10,000 and asks her to hand over the house to him. She pleads

with him to give her some time but he demands that she return the money

within a prescribed time or he would send a lawyer’s notice. He even

insinuates that since she and her daughter were pretty, they

could…Shenbagam laments that god has no eyes or ears to see or hear such

gross injustice. God however comes in the shape of Arunagiri’s son

Sethu who gives her the house document and the loan papers and asks her

to destroy the latter. It is up to children to realize what is right and

wrong, his father may have forgotten his responsibility to take care of

them as part of his family but he had not and he would tackle his

father later. God is not known only by his various names of Eswaran,

Jehovah or Buddha. He is also sympathy, mercy and justice. Music was

composed by Vidhya from existing pieces, nattuvangam by Jayashree

Ramanathan, flute by

Devarajan, vocal by Randhini, mridangam by Jagadish Janardhanan and

violin by Kalaiarasan.

How did Vidhya work upon the story? “This project certainly challenged

me from the get go. Having worked in theatre and some film, the emotive

aspect was more forthcoming for me. However, the way the story talked to

Bharatanatyam was the challenge. First I read the story several times

with each time revealing a new, fresh perspective. Identifying with the

main character was an internal struggle in itself as was relating to the

story. The idea of accepting God in infinite forms, the omnipresence,

the manifestation in all that is good as opposed to the ritualistic

worship that many have reduced spirituality too, was a delightful idea

for me. It is an idea that has revealed itself to me in my life as well.

Once I found this common thread of thought between the author and I (I

spoke to the author's close friend about her approach to life and her

ideas behind the writing process as well), I became more comfortable in

the protagonist's skin. The protagonist is a woman who loses with

potential to lose more. With her faith in God shaken, the same God

appears in the form of compassion in her life. For me it could not be a

verbatim word-to-word depiction of the story, otherwise, it would have

been a drama. It could not have been totally partial to the dance aspect

either or the characters would have been lost. So marrying the two and

making it a dance-theatre piece was my approach.

The music could not use any lyrics as per Natyarangam's instructions. So

I decided to go with existing pieces that would communicate the mood of

a particular scene effectively. I chose to present the positive, the

togetherness of the family unit using the kamas dharu varnam. I used

Asai mugam as a refrain when she loses her husband to relate to how one

doesn't forget the experiences shared with a loved one. I composed a

jati and contrasted it with a swaram for the conversation between the

brother-in-law and the woman, to contrast the evil of one with the

helplessness of the other. I used a tiruppugazh in hamir kalyani which

can be transferred from her despair to the ray of light that shines in

her life in the form of the brother-in-law's son.

I did not want a literal depiction of the story. First and foremost, the

characters would be the woman, her daughter, her son, the

brother-in-law and his son. The woman is the thread through the story. I

decided to start out with the daughter, a teenager doing dance practice

at home and quitting half way through to start admiring herself in the

mirror, something I did as a vain teenager and my daughters do. Then the

son was playing basketball. Then the mother was cooking with the help

of her husband. They all sit down to eat after several times of calling

the children to dinner. Just a normal day in a family's life. But today,

he collapses, changing their lives forever. In choosing to start this

way, I decided to do away with the history between the man and his

brother working in the factory together etc. I wanted to depict their

close-knit, usual family unit first before I showed its breaking in

order to show her sense of defeat. I had also blocked the space so that

each character had his or her own space in the joy and sorrow. The

brother-in-law had to be evil to harass her for the loan he had given

her husband and to threaten to take away her home at the most vulnerable

time of her life. For his son who embodies the element of God, I

decided to show only her reaction to him rather than that character

himself. Throughout the piece, I sprinkled the voice of God and

narrative from the story itself as a constant presence that we question,

discard, accept and subject ourselves to at different times in our

lives. In the mythological parallel of Sudhama-Krishna, God again gives

without being asked.”

The parallel story of ‘Krishna-Sudhama’ is a popular one. They are

childhood playmates. After marriage and children, Sudhama is still poor

while Krishna is the king of Dwaraka. Sudhama’s wife urges him to seek

Krishna’s help and not wishing to go empty handed, he sets out with a

bagful of beaten rice. Dwaraka looks rich and flourishing. Sudhama is

not sure if Krishna would even recognize him, but he does and welcomes

him happily. He asks Sudhama, “What has my sister sent for me?” and

happy to have his favorite food item, he starts eating it. They spend a

few happy days together after which Sudhama, embarrassed to ask for any

favor, leaves quietly. But on reaching his home, he sees it has been

transformed into a palace, his kids are well dressed, his wife is

bedecked in finery and jewellery. None of this matters to Sudhama. For

him, his memories of Krishna are sweetest! Verses from Kuchelopakhyanam

were used. Music was composed by Asha Ramesh.

Aug 16

US based Navia Natarajan was given the story of ‘Asalum Nagalum’ by

Indira Parthasarathy. It was narrated by Thirupur Krishnan. An artist,

who goes to great length to keep the promise given to his young friend,

is in for a shock. The only company for artist Sarangan is 8-year-old

motherless girl Usha who lives with her father and aunt who usually

taunts her for ‘swallowing her mother.’ How can that be, wonders the

bewildered child. She gives Sarangan the newspaper, straightens his

living room, stares at the paintings in his studio. Is he busy? Yes, he

has to complete paintings for an exhibition next month arranged by

Chawla. He’s in need of the money. Can he make a painting of her mother?

Since Sundar looks like his mom, maybe she looks like her mom, she

says. Sarangan asks her to pose for him after school and she tells him

not to tell her aunt as she would be scolded. A beautiful painting full

of soul is the result. Usha asks him to safeguard the painting till she

and her family return from a trip. When he refuses to exhibit this

portrait, Chawla insists that this could be used as publicity at least

and would help to sell the other paintings. A buyer comes forward to buy

all his paintings, but he refuses since he can’t part with the

portrait. The buyer leaves his card in case he changes his mind and

Chawla thinks Sarangan is a fool to let go this opportunity. But

Sarangan has kept his word to little Usha. She returns and he proudly

hands over the portrait to her. But she looks at it for just a moment

and breezily tells him she has no need of it since she is going to get a

real new mother! The unpredictability of children is sometimes beyond

adult comprehension. Even without hearing the story, one could make out

that Navia was portraying a little girl, wide eyed and prancing about.

Music and vocal was by D Srivatsa, sitar by Suma Rani, violin by Eswar,

nattuvangam and rhythm pad by Prasanna Kumar, mridangam by Lingaraju,

flute by Venugopal.

The parallel story of ‘Dhruva’ was the second piece, where the 5 year

old child after being hurt by the harsh words of his stepmother Suruchi,

goes to the forest to do tapas. The Vedic name of the Pole Star is

Dhruva Nakshatra, named after Dhruva, the son of King Uttanapad. The

story is taken from the Bhagavata Purana. A ruler of ancient India, King

Uttanapad had two queens, Suniti and Suruchi. They both had children

named Dhruva and Uttaman respectively. The king loved Suruchi and her

son Uttaman more and wasn't too fond of his first wife Suniti. One day,

he was fondling Uttaman on his lap, when Druva came in running hoping to

be fondled by his father, who was very indifferent to him and didn't

welcome him. Suniti sees Druva hesitating, laughs and tells him that he

should pray to Lord Vishnu, so that he may be born as her son in the

next birth, to be fondled by his father. Dhruva made up his mind to go

deep into the jungle to meditate on Lord Vishnu till the Lord answered

his prayers. On the way he met sage Narada, who tried to dissuade little

Dhruva by warning him about the danger from wild animals, but Dhruva

did not budge from his resolve. Satisfied about the boy’s mental

strength to remain in the jungle, Narada taught him the art of

meditation. Little Dhruva meditated for many months, giving up all

worldly comforts, even food. Amazed at the little boy's determination,

Lord Vishnu finally appeared before him, blessed the boy and told him to

return to his kingdom. In the meantime, heartbroken at the thought of

little Dhruva being devoured by wild beasts, King Uttanapad repented the

injustice done. When Dhruva finally returned safely home, his parents

welcome him with joy. In course of time, Dhruva was crowned king, and

ruled wisely for many years. The dancer switched with ease from dance

movements to yogic poses, without losing balance!

“Choreographing the short story initially was quite a challenge as there

were no lyrics. But as I kept hearing the story (since I can’t read or

write Tamil), I started framing visuals of the story, started working on

lines that gave me more information on the characters, then tried to

think of suitable music that would enhance the mood of the story. The

parallels that I had to draw between the short story and the puranic,

posed a challenge, but having said that, I thoroughly enjoyed my journey

with my characters. It has definitely been an enriching experience and I

have gained a lot of confidence. D Srivatsa's music helped me all the

way, along with the resource person Dr. Sudha and the author,

Parthasarathy uncle. The past few months have been so full of Usha and

Dhruva that I am now going to feel rather empty!” says Navia.

Navia Natarajan

|

Narthaki Nataraj

|

Narthaki Nataraj presented a highly inspired dramatization of ‘Poo

Udhirum,’ a short story by Jayakanthan that was narrated by Sudha

Seshayyan. Periyasami Pillai is an ex-army man who has participated in

two world wars; that is his favorite topic. He loves to reminisce and

feels young men should serve at least 5 years in the army, if not 10. No

surprise he wants his son Somanathan to join the army though his wife

Maragatham is against it. Why is he sending his son to his death? Army

does not necessarily mean death, which anyway is for everyone, he says,

so better to dedicate that life to a cause. Whenever Somanthan is home

on leave, he does not relax but develops a beautiful garden. Young

ladies enjoy plucking the flowers and one such girl Gowri becomes

Somanathan’s bride. The garden blooms even more profusely. He spends

every moment of the two months leave with her and departs, promising to

take her back with him next time. Letters are their only mean of

communication. She is pregnant. He promises to be back for the

‘poochootal’ function and be with her till delivery. As expected, he

sends a letter that he can’t make it for the function as he has to be at

the war front. ‘Like the flower blossoms, it also withers. Likewise,

man is born only to die,’ writes Somanathan. The ‘poochootal’ function

takes place. Somu dies the death of a hero, leaving his wife with

fragrant memories. The child that is born will be a hero’s son. He too

will be a soldier one day. Flowers may wither but new flowers also

bloom. Narthaki’s picturization of a moustache twirling army man who

also smokes was a good touch! Flute and violin were used to play army

tunes to establish the army man connection. The smiles on the faces of

the orchestra members showed how much they enjoyed playing to Narthaki’s

dance dramatization. The final scene of the father giving the hero’s

salute to the photo of his dead son to the plaintive strains of “sare

jahaan se acha…” was a moving touch in the background. It was a

compact presentation, with nothing overdone. The accompanists were

Nandini Anand on vocal, Kalaiarasan on violin, Rathnasubramaniam on

nattuvangam, Nagesh Narayanan on mridangam and Srutisagar on flute. The

voice over was by Sakthi Bhaskar, Arabhi Perinbanathan and

Thirunavukkarasu.

Narthaki says, “When I was a kid, my female relatives were isolated

during their monthly periods and their only pastime then was to read

books that I brought from the lending library. I would read them too. So

I am familiar with all these stories from childhood, including

Jayakanthan’s works. His stories always have difficult subjects and this

story was a challenge. I have seen many retired army men in the

villages, so I was familiar with their mannerisms. Their houses used to

be referred to as “pattaalathukarar veedu.” They would look so tough,

they would do panchayat too and we would be scared to even go past their

houses, we would run! The flower is what binds the narrative for me. In

the garden, the girl Gowri asks her ma-in-law, ‘The house has flowers,

but when will you get a daughter-in-law?’ and she says, ‘Why not you?’

In the second instance, the couple spends happy times in the garden

amidst flowers. In the third instance, I do not show the actual

‘poochootal.’ She measures her flat tummy, stuffs it with flowers as if

pregnant and runs into the garden. When reading out Somu’s letter also, I

let her imagine his face reading it, like in old films. I did not use

any mudra at all, only facial expressions to depict the dialogues. He is

the voice and she reacts to that.”

The evening concluded with the parallel story of ‘Abhimanyu Vadham’

presented by Narthaki in her inimitable style. Abhimanyu was the son of

Arjuna and Subhadra, the half-sister of Lord Krishna. When Subadra is

pregnant with Abhimanyu, Arjuna explains to her in detail, the technique

of attacking and escaping from various vyuhas (an array of army

formation). After explaining all the vyuhas, he explains about the

technique of how to tackle warriors when they surround you in a

chakravyuha or maze during a battle. By now Subhadra is asleep, so he

does not explain how to exit from the chakravyuha and leaves. As a

result, Abhimanyu was born with the knowledge of how to enter a

chakravyuha, but not how to get out of it. Even as a lad, Abhimanyu was

very brave and strong, skilled at archery and was the pride of the

Pandavas. He married Uttara, the daughter of King Virata. She is

pregnant when Abhimanyu goes to the Kurukshetra War where he is made to

enter the powerful chakravyuha battle formation of the Kaurava army.

Arjuna, the only warrior aware of the secret technique to break this

seven-tier defensive spiral formation used by Dronacharya, is away with

Lord Parthasarathy, so Abhimanyu is asked to invade the chakravyuha. The

15-year-old is killed before he can get out. News of the despicable

acts committed on Abhimanyu reached his father Arjuna at the end of the

day, and he vows to kill Jayadratha the very next day by sunset, and if

he failed to do so, would take his own life. Uttara’s son Parikshit

later succeeds to the throne of Hastinapur.

“In those days when they fought wars, there was a sequence – the foot

soldiers, elephant army, cavalry, then chariot brigade. I showed the

appropriate weapons. Abhimanyu goes to war on a chariot pulled by 7

horses. I used sandha chollukattugal from Thiruppugazh for this

sequence. When Abhimanyu leaves for the battlefield, I imagined his

taking leave of his pregnant wife Uttara and wrote my own lyrics,

Mounamum pesumo...pesumay… There is no hugging and crying. The lyrics

say, ‘Who am I to say don’t go? Seeing the pain in your eyes is painful

for me.’ All this in silent pathos, where only the eyes speak and there

are no hand movements. Dharma and Bhima send him to war. He stumbles as

he leaves, an ill omen. Brahma has not given long life to a brave person

like him. Amaravathi is a place where noble, brave souls go after

death. Arjuna laments on hearing of his son’s demise. ‘Did they show you

Amaravathi? Did they show you the karpaga vriksha? Tomorrow I will kill

the one who killed you, or I would go to hell as a bad man.’ So

as not to end on an inauspicious note, I showed Uttara giving birth,

like in olden days when someone steps on the stomach to ease the baby

out,” explains Narthaki Nataraj about her interpretation of the story.

Lyrics from Villibharatam were set to music by Nandini Anand.

Aug 17

On the final day of the fest, Sangeeta Isvaran’s theme was the

importance of nature and the selfishness of man. The story of ‘Anilgal’

written in 1982 was read out by its author Sivasankari and is based on

experience, just as most of her creations are. The young couple move

into a house with a lush garden with different types of trees, home to

many birds and squirrels. Her greatest delight is to watch the garden

and squirrels at play. She can make out which one is strong, good,

brave, a glutton or a Casanova and gives them names accordingly – Bhima,

Hanuman, Sita, some Arjunas and some Krishnas too. She remembers her

landlady yelling at the gardener for letting the squirrels roam free.

Whatever measures he took to get rid of them did not have any effect.

The next year, the landlady got a gypsy to catch them, but he was

ineffective and even left town. The girl is upset over such

happenings. One day, she sees 2 squirrels fallen by a tree. Bhima is

struggling on the asbestos roof. She panics and asks what the matter is.

The gardener says he has strewn the garden with poisoned puffed rice,

and that’s why the squirrels were dying all around. With tears pouring

down her face, she runs into the house.

Sangeeta was the only artiste to have sets for her presentation.

Suspended clumps of ropes, some sack material covering a mound and a pot

were arranged on the right side of the stage. To the soulful strains of

the flute, Sangeeta made a spectacular entry, clad in a beautiful

turquoise and purple costume, brandishing burning incense sticks

sticking out from her fingers like the long, curved fingernails of

Cambodian dancers. She set those into the empty pot where they

continued to spread fragrance through the show. Her depiction of the

squirrels and the beautiful garden, the young lady’s love of nature and

horror at the senseless harm done to the squirrels was well portrayed

with effective abhinaya, without any lag of pace. Music was composed by

MS Suki. The accompanying artistes were many – Murali Parthasarathy on

vocal and konnakol, Kalaiarasan on violin, Jayakumar on tabla, MS Suki

on mridangam, Devaraj on flute, Srividya Vishwanath on veena, M

Balasubramanium on nagaswaram, Rijesh Gopalakrishnan on ganjira.

“When I first read Anilgal, I was struck by Sivasankari's rich

descriptions of the trees and squirrels. I soon realised that the core

rasa of the story, while being deceptively simple, hinged on one vital

point - how can I make the audience identify with the squirrels. Only if

I could draw them into the world of the squirrels - love pretty Sita,

laugh at gundu Bheema and mischievous Krishna - could I then make their

unjustified death a complete shock. So very early on, I set up the

scenes on an emotional graph rather than a logistical one. Making the

music with MS Sukhi was a delight. He listens to the needs of the dancer

perfectly (even when some of them are unreasonable!!) and works

unceasingly, with flashes of true genius when it comes to changing the

mood. It is no joke when one has to make instrumental music for an hour

with no lyrics!

We searched for a variety in sounds, emotions, energies and

techniques. One of my favourites is a superb composition in

Hamsadwani describing the antics of the various squirrels. Sukhi didn't

turn a hair when I told him that I wanted the composition to begin with

the squeaky sound that the nagaswaram produces when you clean the pipe -

evoking the sound squirrels really make! The final effect when we

juxtaposed the squeaks with the quick-running notes on the flute

produced an instant image of the lively squirrels. Right in the middle

of this lively composition where the heroine is completely enchanted by

these small, lively animals, we used dead silence for her husband, to

show his complete indifference to the life around him - he sees nothing,

he hears nothing, he is absorbed in his small world.

My challenge was to make these squirrels come alive within me, so I

watched hundreds of squirrels and invented loads of movements that I

then distilled into a coherent choreography. I had to make the

spectators identify with the love the heroine has for her squirrels, to

the point that when she finds them poisoned, her shock echoes off each

person in the audience; her anger and incomprehension become ours. Why

do these animals have no right to live? How insensitive and incredibly

egotistic can humans be, killing these beautiful creatures to save a few

guavas? That bewilderment and rage came through in an inspired

composition in the last minute in Lavangi. This Lavangi thillana was

composed with the technique that my gurus have passed on to me -

abhinaya from Kalanidhi Narayanan, technique and precision from Savithri

Jagannatha Rao and minute knowledge of the body and angika abhinaya

from CV Chandrasekhar sir,” explains Sangeetha.

In the parallel story ‘Krauncha Vatham,’ (Killing of male crane)

Ratnakar is a cruel hunter and thief. Narada tells him that

stealing and killing animals are sinful and people associated with him

like his family can share the fruits of his bad actions but they can’t

share his sins. Ratnakar asks Narada for his advice. Narada asks him to

chant the sacred name of ‘Rama’ but he is unable to and instead says

‘Mara’ that becomes ‘Rama’ when told continuously. The hunter gives up

his old ways and becomes the peace loving sage Valmiki, who builds an

ashram by the banks of the river and lives peacefully. One day,

Valmiki sees two ‘krauncha’ birds flying about happily in togetherness.

Suddenly an arrow from a tribal hunter hits the male bird and he falls

dead to the ground. The distraught female is beside herself with

anguish. Valmiki's heart melts with pity and he unintentionally utters a

poem rich in grammar and new in metre. This confuses him. Brahma,

the presiding deity of letters, appears and ordains Valmiki to author

Ramayana, the story of Rama, his joys and sorrows for the benefit of the

world.

The happy birds were depicted in an enchanting sequence, a delicate

piece of material serving as wings, and the agony of the slain bird and

the anguish of the surviving bird were well depicted. Hers was a

neat and concise presentation. “I chose

not to focus on the soka of the death of the Krauncha bird - all the

opparis (laments) in the first half were enough, I thought - but take

the leap to Karunya. I chose rather to question the difference between

the unenlightened human, killing without a second thought and the

enlightened one who knows the interconnection of all living things. So I

consciously chose to start with Valmiki as a hunter and his subsequent

transformation into a sage - where 'Mara Mara' becomes 'Rama Rama.'

Subsequently when he faces the hunter who has killed one of the Krauncha

birds, Valmiki curses him for destroying their happiness, replacing

love with death. I intentionally chose this meeting as the focal point

of this piece. Valmiki realises that the hunter is only a reflection of

himself as he used to be, killing for a living. The only difference

between them is that Valmiki has realised Rama, he knows that every atom

in this universe is a manifestation of the Divine.

In the beginning, I was tearing my hair out wondering what to do with

these stories. But slowly the strength of the emotions in each story

took shape, the sets grew, the music became powerful. I really owe all

the musicians a great deal. Without music there is no dance - they were

fantastic! I also have to thank Mr. Gunasekharan, Murielle Lapinsonniere

and P Jagan for making the sets with me. I had no idea that building a

termite mound can be fraught with such peril, that my dog could help me

twist the ropes to make the roots of a banyan tree - suffice to say, I

learnt a lot in every aspect of angika, vachika, aharya and satvika

abhinaya in this project! Natyarangam's webcast ensured a lot more

people saw it - in fact, I already have 3 requests to repeat the

performance by people who saw the webcast. How weird and wonderful is

this world!” Sangeeta is eloquent with her dance and words!

Sangeeta Isvaran

|

Karuna Sagari

|

The festival ended with Karuna Sagari’s performance about two women with

the same indomitable spirit though from different backgrounds. The

first story ‘Maattram' by Poomani was narrated by Sudha Seshayyan, about

how a village labourer raises her voice against unfair compensation for

the work her group has done in the field. Marimuthu and Gomathi, the

ripe old couple has few exchanges to make having been relegated to their

own corners in life. Their only anxiety is the marriage of their

daughter Muthupechi to whom the burden of earning a livelihood is

transferred. She generally keeps to herself. As soon as she

returns from the field, she is engaged in the housework. When the

landowner pays her wages by way of grain she takes it in her hand and

shows the worm infested grain. Amidst the murmur of an angry but

helpless crowd, a clear voice of defiance is heard. Muthupechi refuses

her share saying that it is not alms they have gathered for but their

hard work’s rightful remuneration. She demands to know, “Is this my

wage? What am I to do with grain infested with worms?” which

surprises everyone around. A baffled mason tries to pacify her but she

slowly convinces him that the landlord is as dependant on them as they

are on him. She hints at a boycott and makes him agree. The landlord is

caught between his conscience and ego, but his capitalist instincts tell

him that the boycott might hinder his market share. So, he goes to the

humble home of Muthupechi, to request her father Marimuthu who used to

head the clan as a kothan, to sort out the situation. He promises that

the clan would be given clear grains. When the father asks her if there

was no man to raise the protest, she demands to know why women can’t

protest against injustice. Marimuthu reassures the land owner that

she would report for work the next day and turns to look at his

daughter. There is no regret in the wide open eyes as the laughter

implodes in his mouth. His daughter has inherited not only his hard

work but also the virtue of standing up for what is right.

The morning activities in a village house, work in the fields, carrying

the grain sack over the shoulders, protesting against the rotten grains

and so on were performed suitably, a stick was used to signify the old

people, but there were too many exits and entries in the 20 minute item.

Vocal was by Jyothishmathi, nattuvangam by Karuna’s guru Sheejith

Krishna, Ramesh Babu on mridangam, Ananthanarayanan on veena and

Suryanarayanan on flute. For Karuna, the challenge lay in portraying the

two women. The lady in the first story comes from an underprivileged

background as against the heroine of the second story. “I used konnakol

to show the village waking up. There are 4 main characters in the story,

so I characterized each character with a form of music - raga alaapana

for the main character Muthupechi, thanam for the not so sure kothan,

jathis for the landlord and dialogue and music for the girl’s father. To

establish her hard work, I used the themmangu. The author had written

it and wanted me to use it. Editing the story was difficult. The

scenarios were different every time and also necessitated the presence

of the 4 characters, so that meant many entries and exits. My teacher

Sheejith Krishna gave me the jathis but choreography is my own. He

believes in allowing his students to experiment but is always there to

guide us,” says Karuna.

The parallel story of ‘Manimekalai transforms the king’ is from one of

the 5 great epics that Tamil is renowned for. It was written by

Seethalai Saathanar around the 2nd century AD as a sequel to Ilango

Adigal’s Silappadhigaram. The daughter of Madhavi and Kovalan,

Manimekalai grows up into a beautiful woman accomplished in music and

dance (her grandmother Chitrapati and mother were renowned courtesans)

but refuses to be a courtesan and chooses to become a Buddhist nun and

serve humanity. This noble thought amuses Udayakumaran, the Chola prince

who vows to force her to his palace in his chariot. The first scene is

laid in the garden of the capital city Puhar. He persuades

Manimekalai and her companion Sutamati into the garden. Manimekalai

encloses herself in the crystal pavilion whose gate can be opened only

for people who know the secret entrance. Manimekalai faints inside as

Udayakumaran waits outside. A miracle happens. Her fairy godmother

Goddess Manimekala appears, carries Manimekalai away from Poompuhar to

the southern island of Manipallavam, where she wakes up from her trance,

mystified at the alien surroundings. Here she learns the doctrines of

Buddhism and the true purpose of her life.

Tivatilakai, the divine protector of the land commands her not to rest

till every mouth is fed, and to collect the Amudhasurabhi, the

cornucopia that would never deplete as she continues to serve the

hungry. As soon as Manimekalai collects the vessel floating in the

Gomukhi River, she finds herself back in the crystal

pavillion. Manimekalai starts feeding the poor and needy

with her magic bowl. She serves the ailing and the aged and is reminded

of the criminals in prison. At that juncture, the Chola King Maavan

Killi, hearing of Manimekalai’s selfless service calls her to find out

if his reign is keeping his subjects happy. She humbly puts forth the

thought that the prison is not the place where criminals can be

transformed. The king agrees to her proposal to turn the prison into a

hall of charity where Buddhist monks could meditate, a hospital for the

poor could be established and prison cells turned into centers of

learning.

The sweet voiced narrator gave one half of the story first and the next

part midway through the recital. As against the cotton sari in the first

story, Karuna was clad now in a rich yellow Bharatanatyam costume, and

used a saffron cloth as top garment to show Manimekalai as a Buddhist

nun. The item seemed longer than the 30 minutes and again too many exits

and entries. The artiste drew on the original meter in Sathanar's work

and ‘Manimegalai Venpa' by Bharatidasan. “Manimekalai is not a fictional

character and the story is relevant to today’s times. Hundreds of years

back, she fought for education of the people, and basic needs like food

and health care for the poor and deprived. Why do people become

culprits? Because their basic needs are not met. These people become

worse after being imprisoned. So Manimekalai transforms the jail into a

place where the poor are fed, health care is provided and the place

becomes a learning centre. It’s a contemporary theme, that’s why I made

this item longer. Manimekalai was a very meaningful experience for me.

It allowed a contemporary idea to be expressed through ancient Tamizh.

Artistic challenge was how to portray radically different characters

through dance, costume and props like the dancer Manimekalai, the saint

Manimekala, the lustful prince Udayakumaran, the noble Chola king and

the angel Tivatilakai,” says Karuna Sagari.

There were mixed reactions about the selection of stories. While all the

new stories were narrated, and beautifully too, even a brief synopsis

of most of the parallel stories were not announced, so it was a bit

difficult for a better part of the audience, including dancers, to

follow. At least a basic storyline could have been given. Also, the

announcements and story reading were all in Tamil and with the story

booklet also being in Tamil, it would have been difficult for non-Tamils

to understand what was being done on stage. Availability of an English

booklet would have been much appreciated. Mercifully, the sound system

was at a decent decibel level and we saw smooth transition of orchestra

from one performer to the next. The stage décor was kept simple

and elegant. It was a treat to see the beautiful costumes of varied

designs on all the days. The accompanying artistes for all programs were

exceptional and rasikas including eminent gurus and dancers turned out

in large numbers. The presence of some of the authors of the short

stories like Asokamithran, Sujatha, Indira Parthasarathy and

Sivashankari added to the feel good factor.

Lalitha Venkat is the content editor of www.narthaki.com

|