|   |

|   |

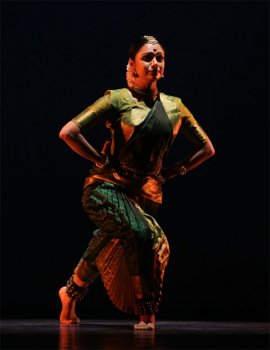

Rama Vaidyanathan’s Akhilam Maduram casts a spell - Sanjeevini Dutta, UK e-mail: sanjeevini@pulseconnects.com Photo: Avinash Pasricha July 3, 2011 Rama Vaidyanathan’s Akhilam Maduram performed at the Bhavan on Sunday 19th June, promoted jointly by Milapfest and Vani Fine Arts is a full- length solo work, evoking the soul of Mathura and Brindavan, the region in North India associated with the life of the god, Krishna. Lyrics written in Brajbhasa by the Bhakti cult saints are set to popular bandeeshes (compositions), by composer and flautist G.S Rajan that weave with dance choreography to create a seamless hour and half of sublime entertainment.  Akhilam Madhuram is in one sense a throw-back to the essence of Indian dance. One could easily transpose the kathakars in the temples along the Yamuna, who sang and danced the episodes in the life of Krishna with Rama Vaidyanathan’s sophisticated Bharatanatyam choreographies of the twenty-first century. The purpose is the same: to tell stories of the Gods through music and movement to entertain and instruct the populace. The opening piece is set to the famous bhajan Madhurashaktam of Vallabhacharya, which speaks of Krishna’s sweetness in every aspect of his being, from his face and features to his dress and walk. Rama springs on to the stage, with a leap holding the murli hasta dressed in a gorgeous shade of Krishna-blue, all energy and verve. She delivers the abhinaya sequences often standing in the sama position, which is unusual as dancers normally adopt a more stylised a-bhang stance. This gives her presence a straightforwardness and directness, which is something of a Rama trademark. The music has delicious pauses, which make one hold one’s breath as the dancer freezes momentarily, cheekily like the boy Krishna, before the rhythm takes over again and we are swept along in its tide. The item is like a painting, rich in imagery of the gopis scurrying along with pots on their head recalling the canvass of Chavda. A perfect overture to the evening’s performance in which the main themes are introduced, well-paced and constructed, we are already entranced. In Navarasa Mohana, Rama cleverly combines the nine-emotions into the description of one episode, that of Krishna entering Mathura with the sole intention of killing his evil uncle Kansa. The reactions of the various groups of spectators from the friends to the elders, the gopis to the kings, each one of the nine emotions are explored. Adopting the shikhara hasta held over right shoulder and left hip, and with one tap on the upper arm muscles, the dancer conveys the confidence and insouciance of the half-boy, half-man Krishna. Equally haunting is the sketch of Kansa with a bowed back, peering darkly into his future. Constructed like a varnam, each of the nine sections of abhinaya is followed by jathis created by Karaikudi Sivakumar and played by Arun Kumar on the mridangam. Excellent vocals by Indu Nair, violin accompaniment by Viju Sivanand and nattuvangam by Dakshina Vaidyanathan are the elements, which give a rich tapestry for the dancer to hang her movements on. In a beautiful conclusion, Krishna comes to the banks of the Jamuna to rest after his trial, at the Vishram Ghat and as the dancer reclines on her back, the lights fade out gently to bring the first half to a close. In the second-half, the theme deepens and takes the audience to another level. Waves of pilgrims make the Brajbhoomi Parikrama, the circular walk around the sacred sites of Brindavan, strumming the ektara, beating on drums, singing in ecstasy. They are Meera, Surdas and Ras Khan who provide the lyrics and they are countless worshippers who throng year after year to look with wonder and awe at the trees and the cows, imagining that they are witness to the boyhood pranks, of the flute playing and cow-herding Krishna. Their devotion conveyed by the dancer transforms the dust of the land into the most precious gold, as it has been touched by the feet of the Lord. Yamuna Teer narrates Krishna’s refusal to do his cow-herding duties on the banks of the Yamuna as the gopis pinch his cheeks. Distraught, the gopis in turn refuse to go as they cannot bear to be reminded of their past in Krishna’s company. Finally, the Ras Leela to the words of Murli naad sunaayoon literally whips up the universe in the ecstasy of dance and music. The gopis are dancing, each with Krishna, but also the cows and the peacocks, the trees and the flowers are all caught up in the expression of the bliss. Rama’s lively choreography at one point has just one-finger and an eyebrow keeping the beat. The lightness of the steps and leaps contrasts with the diamond-cut sharpness of her jathis. There is great variety and variation: space is explored even in executing jathis she covers grounds; strong diagonal lines of pathways with both front and back orientation ensure that the eye of the audience is always engaged. The abhinaya is completely naturalistic and is delivered at a relaxed and unhurried pace. Rama’s work has supreme economy of movement, profundity of content and ease of implementation. She is a dancer like no other who can completely engage the audience in choreographies that have depth without being high-brow. I would call her the ‘people’s princess’ or the ‘princess of people’s hearts.’ Although there is no radicalism, her work is supremely truthful, and I would challenge anyone to watch her and not be moved by it. There is definitely an appeal to the wider public, such as a great composer like Mozart had that his operas spoke to the common man. I believe if a great film director saw her work, he would put her on the silver screen and she would have an audience of millions provided she would actually want that. Sanjeevini Dutta is editor of Pulse magazine, the leading publication for South Asian dance and music in the UK with a global perspective. pulseconnects.com |