|   |

|   |

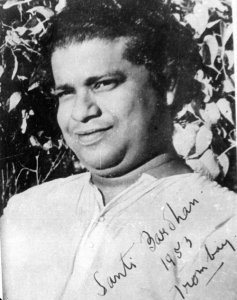

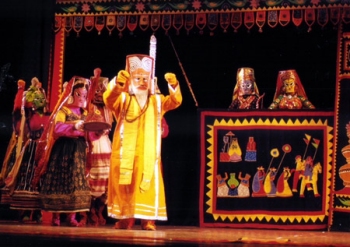

A dazzling piece preserved from the past - Renu Ramanath e-mail: renuramanath@hotmail.com May 21, 2011 The 1950s was a fervent period in the history of India. In the dawn of post-Independence India, the first couple of decades saw a spell of ardent activity in the cultural segment, created with the specific aim of national progress and integrity. The concepts of national integrity and unity were of paramount importance in those days as the very idea of India being a Republic of States with totally differing languages and cultures was itself quite new. The nascent Republic was also witnessing the first queries into modernity across various fields of creative expression, including art, literature, cinema, theatre and dance. The initial attempts to break free of the classical mould (that even the classical dance forms of India were being ‘reinvented’ in this period is another matter altogether) started to happen among the dancers. Key figures like Uday Shankar, the pioneer of modern dance in India, and Shanti Bardhan started their careers in this atmosphere, exploring the country’s rich heritage for creating a new language of expression that would convey the issues of their contemporary society. Organisations like the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and Little Ballet Troupe (later renamed Rangasri Little Ballet Troupe) played significant roles in this cultural cauldron through which the new country was seeking an identity breaking free of the shackles of centuries. Progress, equality, humanism, national integrity and unity – all became watchwords. Even the titles of the works were telling, like Shanti Bardhan’s ‘Bhukhta hai Bengal,’ ‘India Immortal,’ ‘Spirit of India,’ or ‘Discovery of India,’ named after Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s famed volume. These were phenomenally successful in the box-office too. While these works expressed solidarity with the struggles of the emerging nation, the Little Ballet Troupe’s Ramayana Human Puppet Ballet, stands apart as a simple and straightforward re-telling of the Ramayana story. However, its relevance lies in the fact that the troupe, all the while struggling for its own survival, managed to preserve this ballet or dance-drama to this date, which they still continue to perform without losing even an inch of their initial perfection. And also that Shanti Bardhan chose to narrate the story of Ramayana as a humane tale, devoid of all divinity and miracles.  Shanti Bardhan Choreographed by Shanti Bardhan, a close associate and disciple of Uday Shankar, and staged for the first time in 1953, the Ramayana Human Puppet Ballet is a unique production in the history of modern dance in India, as a dance-drama designed emulating a puppet theatre performance. For the entire length of the performance, the dancers wearing puppet-like masks move like puppets, with intricate footwork that Shanti Bardhan, with his 12-year-long training in Manipuri and Tippera had culled from the vast treasury of India’s classical and folk dance forms. The costumes, along with the ingenuously crafted masks enhance the puppet-like appearance of the dancers.  Appunni Kartha Interestingly, the most exceptional aspect of this production happens to be these puppet-like costumes and masks, which were designed and made in 1953 by AP Appunni Kartha, a rather elusive figure from the history of LBT and IPTA. The only available bio data about him merely mentions that he hails from Kerala and started associating with IPTA in 1944, along with Shanti Bardhan, then a young, aspiring dancer hailing from Bengal. Later, he completed the choreography of ‘Panchatantra’ after Shanti Bardhan’s death and continued to work with LBT, often travelling abroad as a cultural emissary attending various festivals. A gifted dancer trained in Manipuri and the rarer Tipperah schools of dance for almost 12 years, Shanti Bardhan was also associated with Uday Shankar for six years in Almora. The IPTA formed in 1942 was the Communist Party of India’s cultural wing, working for spreading the party’s ideologies and messages through theatre, dance and music. Many leading cultural personalities of those days like KA Abbas, Ritwik Ghatak, Prithviraj Kapoor, Utpal Dutt and Salil Chudhury had associated with IPTA. Though Shanti Bardhan and Appunni Kartha parted ways with the IPTA, forming Little Ballet Troupe in 1952, the core spirit of humanism, anti-imperialism and radical experimentation in form was carried on.

Shanti Bardhan was obviously inspired by the Rajasthani string puppets, the Kathputli, while choreographing this innovative dance drama. The dancers wear square wooden masks on which the puppet faces are painted. The ballet is presented as a puppet performance taking place in a village fair, with the bare minimum sets which are colourful nevertheless. One interesting stroke of genius in the play is the replacing of the dancer enacting Sita with a doll in the abduction of Sita by Ravana. The Ramayana Human Puppet Ballet hardly looks like an old choreography. The 50 plus years fade out as the dancers start to move about with the intricate footwork and perfect movements. The costumes and masks, hand crafted by Appunni Kartha more than half a century ago, looks fresh and bright, thanks to the meticulous care with which the LBT members take care of their precious legacy. The precaution is so much that the audience who gathered at the open air auditorium of Guru Gopinath Natanagramam at Vattiyoorkkavu near Thiruvananthapuram had to wait patiently for hours into the night till the slight drizzle of summer showers completely stopped before the troupe agreed to perform. The organisers of the World Dance Forum, organised under the auspices of the upcoming Guru Gopinath National Dance Museum, had no other option but to pray to the rain gods, as the LBT members categorically refused to let even one drop of water fall on their precious costumes. At last, when the rain stopped, the program was started on one condition – the moment a drop of rain falls, the performance would be stopped. Thank god, it didn’t rain after that! And, the ‘human-puppets’ played to the end, moving to the unseen strings. No wonder, for the LBT members, every performance of the Ramayana ballet means an unending headache, with the transportation and handling of these precious relics from the past. In their heydays, this dance drama was performed to a live orchestra consisting of around 16 musicians, who sat on the stage. But, the struggles of survival forced them to do away with the live music. Now, the dancers perform to an old recording of the same music. Though they plan to get the music re-recorded, there is an apprehension that it might not have the vitality of the original. Likewise, all attempts to make another set of the costumes and masks had also proved futile, as no one could reproduce the life and dynamism that Appunni Tharakan’s hands had bestowed upon the originals. That Shanti Bardhan created this unique production after recuperating from a major surgery of his lungs that saved his life (albeit temporarily) from the clutches of tuberculosis is quite telling. He was left penniless and alone. And he could no longer dance. However, the Puppet Ramayana turned out to be his solution to all these crises.  Gul Bardhan The credit for having preserved this gem of a choreography for almost 60 years rests with the late Gul Bardhan, who took on the arduous task of continuing her husband’s dream since his untimely death in 1954. Gul Di, as she was addressed by all her close associates, led the group till her death on November 28, 2010 at the age of eighty two as the moving spirit and lead dancer, performing well into her eighties. Honored with a Padma Sri amidst several other awards, Gul Bardhan had fought many odds down the decades for maintaining the LBT. Born in a Gujarati family, she at first became Shanti Bardhan’s disciple, and later, life partner and continued the work left incomplete by Shanti Bardhan after his death. With the help of dynamic personalities like the gifted choreographer Prabhath Ganguly and Appunni Tharakan, she carried on the legacy with missionary zeal. In many interviews, she had remembered the staunch support that came from Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi. She had also edited ‘Rhythm Incarnate,’ a volume on the life and works of Shanti Bardhan. Renu Ramanath is a writer and columnist based in Kochi. She has covered art and culture extensively for The Hindu as a Staff Reporter in the Kochi bureau from 1996, writing reviews and features in The Hindu Friday Review and Sunday Magazine. Currently she edits Art Concerns, an online journal for contemporary Indian art. |