|   |

|   |

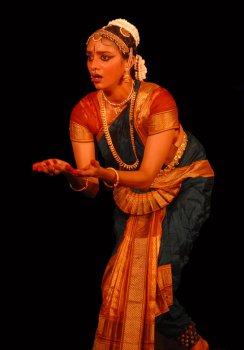

The artistry of Athreya - A Seshan, Mumbai e-mail: anseshan@gmail.com Photo courtesy Lakshmi P Athreya March 16, 2011 Lakshmi Parthasarathy Athreya, a leading student of Chitra Visweswaran and front-ranking dancer of the younger generation, gave an impressive performance, based on Margam in a capsule form, at the Little Theatre of the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Mumbai on March 10, 2011. She is an architect by profession. The programme once again proved the popularity of the much neglected traditional format of Bharatanatyam. The auditorium with a capacity to accommodate 100 persons was full and they intensely followed the dance from the beginning to the end expressing their appreciation at appropriate times. The small theatre has its own advantage as it provides an intimate atmosphere for the rasikas to follow not only just the dancer's movements but the facial expressions of navarasas also. This is not possible in bigger theatres where for those in the back seats the dancer could look like a marionette with no identification of the face. The programme commenced with a recorded prayer "Vara Vallabha" in Hamsadhwani, adi, a composition of GNB, sung by his nephew the late R Visweswaran. He was a multi-talented vidwan. It brought back a flood of memories of my listening to him in the past. He had a mellifluous voice and used to accompany his wife in her dance performances. I still remember his rendering of "Krishna nee begane baro" in a TV concert a few years ago.  The regular concert started with Ganga Kautuvam, a Pravaha Anjali (tribute) to the river Ganges in Purya Dhanasri, composed by Visweswaran, followed by "Jaya Gange" of Chitra Visweswaran, portraying the qualities of Ganga. Then followed the piece-de-resistance of the evening, a varnam that lasted nearly 35 minutes in the totality of dancing for about 90 minutes. Lakshmi did full justice to all the aspects of the varnam by Lalgudi Jayaraman ("Innum en manam") in Charukesi and adi. Chitra told the audience that the song had been composed by the violin maestro specially for Kamala Lakshminarayanan, the doyenne of Bharatanatyam. The lyric describes the human body as a flute and the breath as the energy flowing through it. Life itself is a magical manifestation of Krishna's flute. The line "Kuzhaloodum" was replete with sancharis that brought forth Lakshmi's expertise in portraying several emotions of the nayika lamenting the indifference of Lord Krishna. The portrayal of the puja done by the devotee to her lord was realistically done in the Natyadharmi mode. With the emphasis on bhakti sringara as the sthayibhava, there was no storytelling of the exploits of the god. There is a school of thinking in the Bharatanatyam world which holds the view that varnam is not the place for storytelling. The sanchari bhavas should be the medium for the manifold expressions of rasas. As originally envisaged, they are meant to provide myriad facial expressions on every line for showing skills in abhinayam. However, storytelling has certainly a place in slokas and kirtanas. (See the review: "Prof. Chandrasekhar at Nalanda Seminar" ). The nayika is an angry young woman - khandita - but with a gentle touch - pragalbha. As Chitra explained, she makes her criticism not in a stinging or hurting way but gently like the piercing of a banana with a needle. This aspect was well brought out by Lakshmi. The tirmanams were crisp with full control over kalapramanam. "Aduvum solluval, anekam solluval," a popular padam of Subbarama Iyer in Saurashtram and adi, portrayed a pragalbha nayika of the uttama type. She is gentle in remonstrating against the infidelity of the nayaka and sarcastic about the new-found affluence of the other woman. The Purandaradasar kriti ("Ninyako Ranga", Ragamalikai, adi) provided scope for storytelling. Lakshmi effectively portrayed the destruction of Hiranyakashipu in Narasimhavatar, the saving of Draupadi's honour in Mahabharata and the Dhruva story. I liked her portrayal of Narasimhavatar. Generally, in enacting this episode, there is a tendency for the average dancer to put out the tongue, assume a terrifying mien displaying fearful claws and mercilessly taking the hell out of the heart and life of the rakshasa in a dramatic manner. While it befits a male artiste behaving like a Rottweiler pouncing on a victim, it does not sit well with a young and beautiful female dancer. With the guidance of her guru-cum-choreographer, Lakshmi achieved the impossible artistry of portraying Narasimha's destruction of the asura without descending to the lokadharmi mode. The krodha of Narasimha was not coarse but dignified befitting his stature. The song in Ragamalikai (Hamsanandi and Sindhubhairavi) glided smoothly into Madhurashtakam of Vallabhacharya sung in Brindavana Saranga. Tandava and lasya elements were interwoven. Tillana, composed by Visweswaran, was ingeniously incorporated into the piece. But I felt that a full-fledged tillana would have been a fitting climax to the evening of a recital on classical lines. As choreographed, there was only limited scope for the neck and eye movements and statuesque poses that one normally expects of this item. What impressed me most in Lakshmi was the free flow of movements. There was no rigidity or stiffness in limbs and dancing seemed to have become second nature to her. And whatever she did, be it skalitam or utplavana or brahmari, was aesthetic without showmanship. The adavus, marked by anga suddha, were on sastraic lines. Footwork was gentle. Sitting in the front row, I did not hear the harsh thud of the foot striking the floor. The arm movements stretching all the way down to touch the toes were typical of the Vazhuvoor bani in which Chitra had training under Ramaiah Pillai. Many dancers, either due to their bani or, more probably, physical constraints, are not able to reach out to the toes and stop midway. Her soft approach to vigorous movements was such there was no hard panting for breath at the end of the varnam as we see in many cases. However, she could have entered the stage for every item with dancing steps. The supporting orchestra was an important contributor to the success of the programme. After a long time I saw a live orchestra on stage at the Little Theatre. That it makes a difference to the quality of the performance was evident. The orchestra was led by Chitra on nattuvangam, supported by Sivaprasad (vocal), Satish Seshadri (violin) and Satish Krishnamurthy (mridangam). Kudos to Chitra Visweswaran for the excellent choreography emphasising the essentials and eschewing drama. Her recitation of sollus was energetic. The elongation of consonants in jatis with the appropriate extension of the hand by Lakshmi reminded me of the synaesthetic approach of the Jayammal-Balasaraswati School ("See the music, hear the dance"). Her detailed explanation of the lyric before every item was helpful to the cosmopolitan audience to follow the dance. There was vallinam/mellinam (hard and soft notes/beats) in the performance of the vocalist and the mridangist. But I felt that, if the vocalist had raised his sruti a little more, his singing would have had more punch. Charukesi sounded flat at times. A Seshan, an Economic Consultant in Mumbai, is a music and dance buff. He is a regular contributor to narthaki.com. |