Glimpses

into the past, present, and future of solo dance

- Ketu Katrak

e-mail: khkatrak@uci.edu

Photos: Miles

Brokenshire June 20, 2010 A provocative

title 'Solo Dance' catches our imagination during an excellent Symposium

(June 4-5, 2010) exploring "Perspectives from South India and Beyond",

presented in Toronto, Canada, by InDance in collaboration with the Royal

Ontario Museum and Friends of South Asia. The gathering included dancers,

choreographers, and scholars from India, North America, and Europe. This

event, distinctive in its careful curatorial organization, was a realization

of the vision of Hari Krishnan, Artistic Director of InDance and Davesh

Soneji, scholar of South Indian history, both deeply knowledgeable about

solo dance from South India, "particularly in its manifestation" notes

Krishnan in the Symposium booklet, "as Bharatanatyam [that has] emerged

as a global signifier of South Asian culture." The Symposium was delightfully

balanced between performances of present day Bharatanatyam and Contemporary

Indian dance, and scholarly papers traversing the history of devadasi

dance in the 19th and 20th centuries including its transformation by nationalist

and Brahmin influences. Dancers from India and North America appropriately

had the last word in a closing Plenary where they shared their processes

of creative choreography, and discussed challenges and rewards of doing

solo work in the late 20th and 21st centuries.

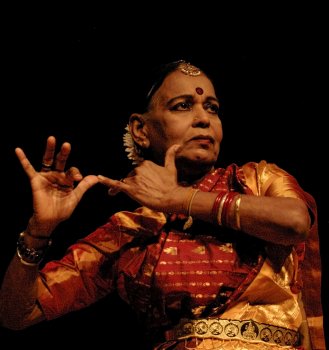

Saskia

Kersenboom

Saskia

Kersenboom

|

A profound sense

of reverence opened the Symposium with "the first songs (and ritual dances)

greeting the gods" in the temple, rendered expressively by Saskia Kersenboom,

who has studied the repertoire (for nearly twenty years) from P Ranganayaki,

dedicated to the Murugan temple in Tiruttani (Tamilnadu, South India) in

1931. Ms. Kersenboom conveyed a deeply devotional feeling with gentle lyrics,

taking the audience through the daily rituals punctuating different times

of the day until nightfall when she sang the gods to sleep with the sweet

lallis (lullabies). The tone was

set for the Symposium's showcasing of solo performing artists, and the

many-faceted discussions of hereditary devadasis as the original

custodians of music and dance. The Keynote by Professor Janet O'Shea, two

Special Sessions by noted musicologist scholar, BM Sundram, and dance critic

Sunil Kothari, three panels with nine speakers covered a rich terrain of

well-researched papers with accompanying visuals. O'Shea addressed

the complex terrain of solo dance usually associated with tradition, and

group/ensemble work with innovation or experimentation. She both investigated

and challenged these categories and examined competing aesthetics facing

solo dance in the 21st century. Dr. Sundaram recounted anecdotes of meeting

devadasis, including their resistance to unfair branding of their

profession and their efforts to fight the 1947 legislation banning their

practice. Although they did not succeed, Dr. Sundaram drew attention to

their "radical forms of resistance and artistic virtuosity." Kothari's

screening of Venkatalakshamma's abhinaya - a devadasi from

Karnataka, provided rare visual documentation of how solo dance "was preserved

and supported by the ruling elite of Mysore."

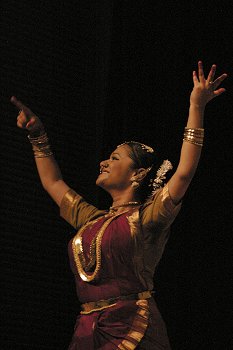

Anita

Ratnam

Anita

Ratnam

|

Patricia

Beaman

Patricia

Beaman

|

Solo dance performance

by Anita Ratnam in a spell-binding 15-minute version of her longer piece,

7 Graces that references the goddess Tara of Tibet, and evokes the

"feminine transcendental" was introduced by Krishnan as "non-linear, using

mythology as metaphor, even abstracting mythology and movement as maps

to navigate inroads into new movement and contemporary sensibility." A

neo-baroque solo by Patricia Beaman, Accumulating Venus uniquely

"deconstructed the Passacaglia de Venus (1725)" as noted in the program,

"juxtaposed with modern themes of celebrity, rejection, sensuality and

power." Leela Samson's talk, 'Reflections on my Journey' was interspersed

by a moving performance of her Bharatanatyam choreography including a dance

to a North Indian thumri.

Leela

Samson

Leela

Samson

|

Shyamala

Shyamala

|

Other memorable

performances included a "Plenary dance performance of Padams and

Javalis: Solo dance as crafted by T Balasaraswati," rendered by

a senior disciple, Shyamala. Bala's unique abhinaya style where

the soloist moves with the talam even as she interprets the lyric

poetry was exquisitely brought to life via Shyamala's flowing abhinaya,

and ease of moving with the different talams. Another performance

highlight was InDance's presentation of "Nineteenth-century solo dance

repertoire in the twenty-first century," honoring the memory of devadasi

dance with live orchestra wherein scholar Soneji wore his nattuvanar

"hat" most ably. It was heartening to see Krishnan's rigorously trained

and expressive multiethnic dancers, present five solos from the devadasi

repertoire learnt by Krishnan from hereditary performers. Indeed, despite

legislation to eliminate devadasi dance, it has survived. An added

delight was to see Krishnan himself dance with Srividya Natarajan in an

energetic choreography of solo dance re-interpreted as a duet, a successful

"choreographic experiment pushing the form of the svarajati." Krishnan

introduced (with power-point) each dance item's technique, time-period,

and composer with keenly researched historical material.

Srividya

Natarajan and Hari Krishnan

in Chakravakam

Svarajati

Srividya

Natarajan and Hari Krishnan

in Chakravakam

Svarajati

|

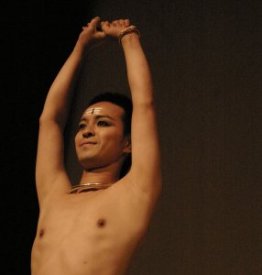

inDance's

Hiroshi Miyamoto

in Kaivara

Prabandham

inDance's

Hiroshi Miyamoto

in Kaivara

Prabandham

|

Among the nine

scholarly papers, a few made original contributions to dance scholarship

such as Joep Bor and Tiziana Leucci's fascinating discussion of "The European

performances of five devadasis in 1838 and 1839." Bor and Leucci

traced the devadasis' 18-month journey (with three musicians) from

a Vishnu temple in Pondicherry brought to France by impresario EC Tardivel.

As noted in the Symposium brochure, they were "billed as the 'real' Bayaderes

or Priestesses of Pondicherry" landing in Bordeaux on July 24, 1838, the

first devadasis to travel to Europe, dancing for the French royal

family at the Tuilleries and becoming "instant celebrities." Bor and Leucci's

extensive archival research into articles and newspaper reviews conveyed

positive ("they dance not only with the feet but the whole body") and negative

("they speak a language in their dance resembling that of the deaf and

dumb in gestures") impressions of the devadasis during the Orientalist

vogue in Paris of the 1830s, and their influence on major French ballerina

Marie Taglioni, even Anna Pavlova. Their impact continued even after they

left Europe.

inDance's

Nalin Bisnath in Kuravanji

inDance's

Nalin Bisnath in Kuravanji

|

inDance's

Shobana Raveendran in Salam Daru

inDance's

Shobana Raveendran in Salam Daru

|

inDance's

Sreyashi Chakraborti in Modi

inDance's

Sreyashi Chakraborti in Modi

|

inDance's

Vinod Shankar in Jatisvaram

inDance's

Vinod Shankar in Jatisvaram

|

Davesh Soneji,

in "Salon to cinema: Telugu Javalis in colonial South India" discussed

the origins of the javali, as "a musical and literary form" in the

19th century Mysore court. Javalis in Telugu and Kannada languages

were "modern songs" as noted in the program, "modeled on the older Telugu

padam genre . . . performed by devadasi-courtesans during

salon performances patronized by elite Brahmins and landowning communities."

Soneji noted a fascinating historical detail - many javali composers

were in the colonial civil service as clerks or postal workers. Although

the javali's life was short, they were performed in early Telugu

cinema. Soneji made a useful scholarly intervention in using the words

"devadasi / courtesan" interchangeably, thereby asserting a sense

of solidarity among South and North Indian artistes who performed monumental

service in preserving the arts. Kersenboom added that not all devadasis

were dedicated to temples and that it is important to underline the prayoga

(environment, context) of the temples with many-faceted duties."Twentieth

century shifts in solo dance" panel included Teresa Hubel's useful historical

analysis about "the suppression (though not the destruction) of the matrilineal

culture of the dancing women of South India," its transformation into middle-class

notions of femininity that persist today even in the diapsora. Srividhya

Natarajan discussed "the social and psychic dimensions of the relationship

between the nattuvanar dance teacher" and a feminist student,

also noting caste and class hierarchies. Anne-Marie Gaston's "Living the

transformations in Bharatanatyam from 1964 to the present" shared research

on solo dancers moving from Chennai to Delhi in the 1970s where they encountered

the synergy of different Indian dance styles.

Symposium

group

Symposium

group

|

The final panel,

"Reflections on Contemporary solo dance, identity, and selfhood" included

papers by Ketu Katrak analyzing the interplay of dance and theatre in the

work of Los Angeles based Post-Natyam Collective's artist Shyamala Moorty;

by Chitra Sundaram on South Asian dance in Britain having become "a spectacle."

Sundaram noted Shobana Jeyasingh's major contributions in contemporizing

Bharatanatyam that paved the way for Akram Khan's "paradigm-shifting" movement

work. Rathna Kumar delineated her dance journey for 35 years in Houston,

Texas and the increasing requests for group dance, short items, and Bollywood

style dance.Overall, the

Symposium was an exhilarating experience of two packed days with transcendent

moments of joy in witnessing performances and path-breaking intellectual

challenges of scholarly discourse and discussion. As a participant, I would

eagerly welcome a follow-up Symposium on the rich history of Indian solo

dance that enlightens our current performance practice and scholarship

in the 21st century.

Ketu H Katrak,

University of California, Irvine. |