Erasing

Borders: Festival of Indian dance: A reflection

- Diditi Mitra

e-mail: diditimitra@aol.com

August 27,

2008

The recent

Indian dance festival sponsored by the Indo - American Arts Council in

New York City concluded with a set of performances that varied in their

content, dance styles and their choreographies. This review is based on

the performances on the final evening of the festival. A total of six companies

presented their works that evening. While the performances by Dakshina/Daniel

Phoenix Singh Dance Company's presentation of Bell Song and Sinha

Danse's presentation of Quebasian Rhapsody elevated my spirits with

their thoughtful and exciting exploration of movement, space and music,

the presentations of Sath Safed by Maria ColacoDance and Daak

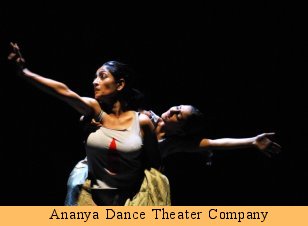

by Ananya Dance Theater Company forced me to focus on the disadvantaged

workers of the developing world. In contrast, Carmine Bees presented

by Sudarshan Belsare and Ardhanarishwara by Nayikas Dance Theater

and Rudrakshya used mythologies from Buddhism and Hinduism respectively

in order to challenge patriarchal social expectations. Together, the diverse

dance forms and the diverse content of the choreographies compelled me

to ponder the meaning and the possibilities of "erasing borders."

Expanding

one's sense of self and space that embraces stories of people who are seemingly

different is one pathway to "erasing borders." Maria Colaco's choreography

on the Kashmiri carpet weavers attempted to do so by stretching the national

and cultural borders to include stories of people that are clearly distinct

from hers as a South Asian American woman. Similarly, Ananya Chatterjea's

performance on the ongoing struggle for land rights by women of Nandigram,

West Bengal demonstrated a need to widen one's world to include places

and people who may seem disconnected from our everyday lives, but are certainly

part of the global space that all of us inhabit. A global social consciousness

and a desire to understand connections between multiple social realities

that were evidenced in the choreographies of Colaco and Chatterjea are

certainly commendable and much needed. Expanding

one's sense of self and space that embraces stories of people who are seemingly

different is one pathway to "erasing borders." Maria Colaco's choreography

on the Kashmiri carpet weavers attempted to do so by stretching the national

and cultural borders to include stories of people that are clearly distinct

from hers as a South Asian American woman. Similarly, Ananya Chatterjea's

performance on the ongoing struggle for land rights by women of Nandigram,

West Bengal demonstrated a need to widen one's world to include places

and people who may seem disconnected from our everyday lives, but are certainly

part of the global space that all of us inhabit. A global social consciousness

and a desire to understand connections between multiple social realities

that were evidenced in the choreographies of Colaco and Chatterjea are

certainly commendable and much needed.

However,

Colaco and Chatterjea's choreographies would have been strengthened by

a more careful consideration of the contexts in which the Kashmiri carpet

weavers and the women of Nandigram are located. The costumes that reflected

the aesthetic of the local were an important way in which the stories could

have been contextualized. Whereas the dancers in Sath Safed wore

costumes that are typically associated with modern dancers, the dancers

in Daak wore costumes that reminded me of army fatigues. It was

difficult for me to relate the bodies on stage to the people whose stories

were being told. The static dance movements and the facial expressions,

especially in Daak, may have also been a reason why I was unable

to visualize and feel the people on whom the narrative was based. Additionally,

the choice of background score exoticised the local. Burial and/or marketing

of the local in order to imagine the global only silenced the voices from

below and reproduced the very hierarchies that Colaco and Chatterjea set

out to dismantle. However,

Colaco and Chatterjea's choreographies would have been strengthened by

a more careful consideration of the contexts in which the Kashmiri carpet

weavers and the women of Nandigram are located. The costumes that reflected

the aesthetic of the local were an important way in which the stories could

have been contextualized. Whereas the dancers in Sath Safed wore

costumes that are typically associated with modern dancers, the dancers

in Daak wore costumes that reminded me of army fatigues. It was

difficult for me to relate the bodies on stage to the people whose stories

were being told. The static dance movements and the facial expressions,

especially in Daak, may have also been a reason why I was unable

to visualize and feel the people on whom the narrative was based. Additionally,

the choice of background score exoticised the local. Burial and/or marketing

of the local in order to imagine the global only silenced the voices from

below and reproduced the very hierarchies that Colaco and Chatterjea set

out to dismantle.

Using the available

cultural tools to raise questions from within in order to question social

boundaries is another avenue to "erasing borders." This was precisely the

intention of the performances by Sudarshan Belsare and Nayikas Dance Theater

and Rudrakshya. Belsare's work used Buddhist mythology based on the story

of the goddess Kurukulla in order to question dominant notions of maleness

as a prerequisite for the achievement of enlightenment. The performances

by Nayikas and Rudrakshya, in contrast, used the dance idiom of Odissi

to depict the idea of the Ardhanarishwara in order to critically

reflect on the socially constructed borders of male and female that comprise

gendered social arrangements. While a noble objective, the choreographers

needed to place this "nonsexist" tool within the broader frame of sexism

that is very much a part of at least Hinduism. Also, the sacred thread

worn by the dancers in Rudrakshya that represent membership in the upper

castes within the Hindu tradition challenged the choreographers stated

goal of "erasing borders."

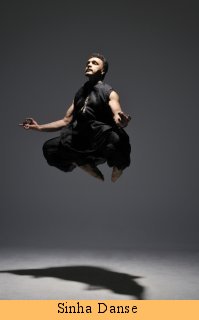

Integration

of diverse cultural forms for the development of something new is another

way to break down barriers. I found Daniel Phoenix Singh and Roger Sinha's

mélange of at least modern and Bharatanatyam to be absolutely delightful.

Their dancing reflected their versatility and their skillfulness as dancers.

The ease with which they moved demonstrated their embodiment of both modern

dance and Bharatanatyam. Their keen musical sensibilities were also reflected

in their choice of music and its use as a tool to enhance their performances.

The effective use of space by both groups of dancers further enhanced their

choreographies. Through their choreographies, both Singh and Sinha, were

able to show the importance of respecting the local for an honest attempt

in "erasing borders." Integration

of diverse cultural forms for the development of something new is another

way to break down barriers. I found Daniel Phoenix Singh and Roger Sinha's

mélange of at least modern and Bharatanatyam to be absolutely delightful.

Their dancing reflected their versatility and their skillfulness as dancers.

The ease with which they moved demonstrated their embodiment of both modern

dance and Bharatanatyam. Their keen musical sensibilities were also reflected

in their choice of music and its use as a tool to enhance their performances.

The effective use of space by both groups of dancers further enhanced their

choreographies. Through their choreographies, both Singh and Sinha, were

able to show the importance of respecting the local for an honest attempt

in "erasing borders."

So, I come

back to the two questions I raised in the beginning of this review. Firstly,

is it possible to "erase borders?" The uneven global space that we occupy

makes it difficult to do so. At least in the works of Chatterjea and Colaco

what I presumed is a desire to erase signs of the local in order to make

the product palatable to the "global" (read: Western) audience. This form

of packaging of issues by both choreographers was likely to have fed the

Western liberal mind that feels the need to rescue the oppressed, especially

those in the Third World. In that case, instead of "erasing borders," the

existing ones are simply being reinforced. Secondly, what does it mean

to "erase borders?" As the performances of Singh and Sinha show, it is

necessary to attain deep knowledge and understanding of the local in order

to build bridges and create a kind of global that is able to respect and

grant legitimacy to all involved. To put it in a slightly different way,

understanding the self, howsoever defined, is a necessary prerequisite

for building relationships, and hence, it is also a necessary prerequisite

for the eventual erasure of borders.

Diditi

Mitra is a Sociologist, Kathak dancer, and a member of Courtyard Dancers,

a Philadelphia based dance theater group. |