De-ritualisation and Re-contextualisation:

The shifting performance ecology of Bharatanatyam in the 21st century

- Dr. Amrita Sengupta Dutta

e-mail: dramritasenguptadutta@gmail.com

November 4, 2025

Abstract

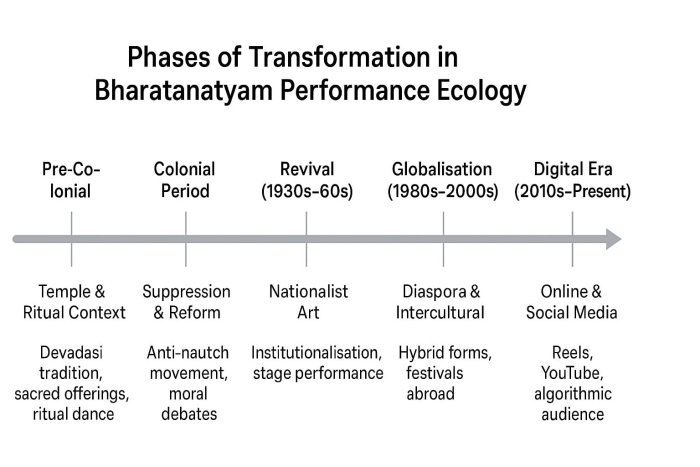

Bharatanatyam, originally woven into the ritual and devotional life of

South Indian temple culture, has traversed a complex path of

transformation over the last century. From its deep association with

temple worship and the devadasi system to its redefinition during the

colonial and nationalist eras, and its subsequent digital and global

incarnations, Bharatanatyam continues to evolve amid changing social,

political, and technological landscapes. This essay investigates two

interconnected processes - de-ritualisation, referring to the dance's

gradual detachment from its sacred roots, and re-contextualisation,

which signifies its adaptation within modern cultural, ideological, and

digital environments. Employing a narrative research framework, the

study explores how globalisation, feminism, diasporic identity, and

social media cultures have reshaped Bharatanatyam's performance ecology,

creating an ongoing negotiation between tradition and innovation.

Introduction

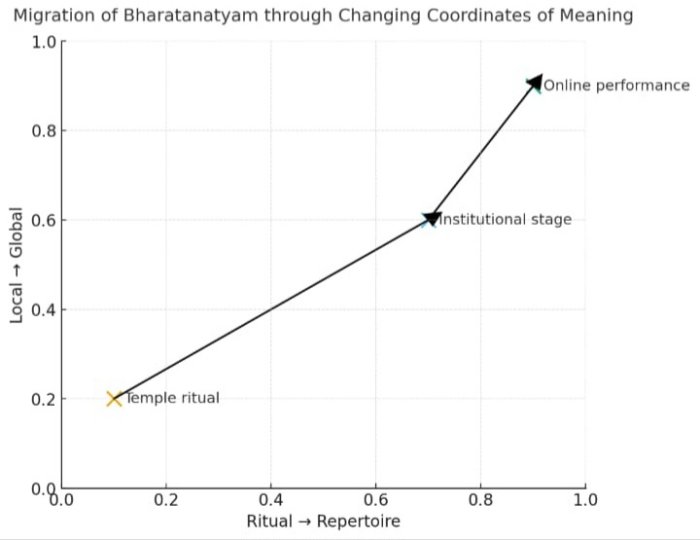

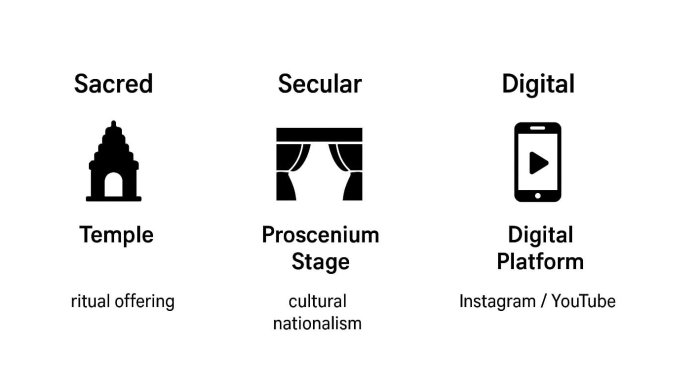

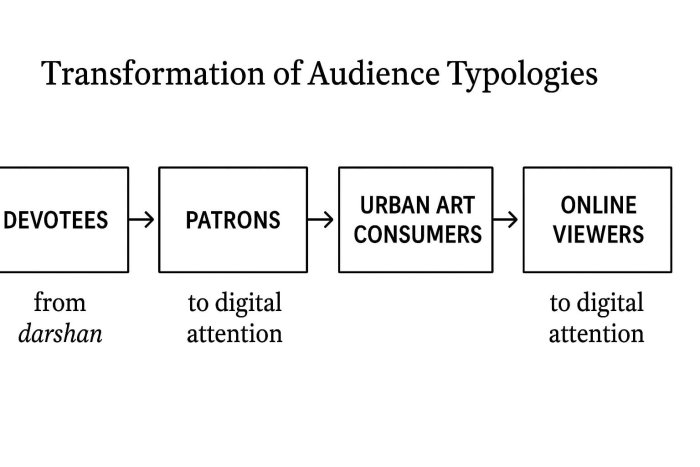

The evolution of Bharatanatyam from the inner sanctums of South Indian

temples to international stages and digital platforms exemplifies one of

the most remarkable metamorphoses in Indian classical dance history.

Rooted in the Natya Shastra and once nurtured through the sacred

practices of the devadasis, Bharatanatyam traditionally functioned as an

act of seva - a spiritual offering rather than public entertainment.[1]

However, colonial ideologies, nationalist revivalism, and reformist

movements gradually severed the dance from its ritual foundations,

reimagining it as a symbol of India's cultural identity.

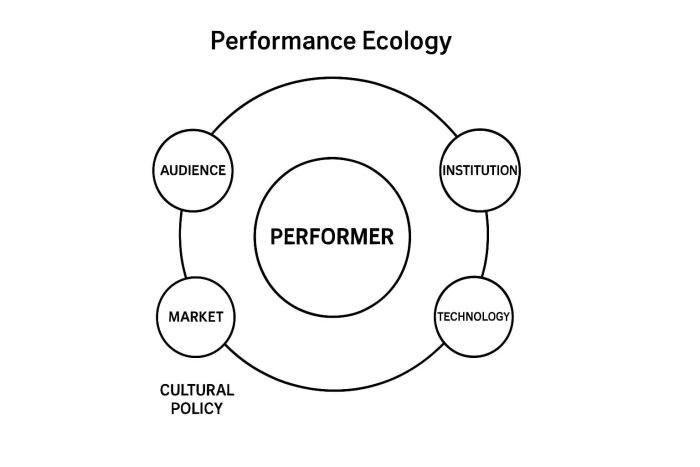

In the contemporary era, Bharatanatyam transcends institutional

boundaries, thriving in online spaces, short-form videos, and

international festivals. The process of de-ritualisation denotes its

movement away from temple-based sanctity, while re-contextualisation

marks its transformation into secular, pedagogical, and digital

frameworks. Together, they constitute a dynamic performance ecology - a

complex network of artists, audiences, platforms, and ideologies that

collectively redefine the meaning of Bharatanatyam today.

Historical Grounding: From Ritual to Revival

Bharatanatyam's sacred origins lie within the ritual and temple culture

of Tamil Nadu. The devadasis - women dedicated to temple deities - performed

the dance as part of sacred ceremonies. The Sadir repertoire,

comprising alarippu, jatiswaram, varnam, and padam, expressed both

spiritual devotion and aesthetic sophistication.[2] The abhinaya

(expressive storytelling) and nritta (pure dance) components were

harmoniously interwoven with music, poetry, and spirituality.

However, during the 19th century, British colonial moralities and social

reform movements began to stigmatise the devadasi system as "immoral."

Reformers like Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy led campaigns against temple

dancing, culminating in the Madras Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication)

Act of 1947.[3] Paradoxically, even as the ritual practice was banned, a

simultaneous revival was initiated by figures such as Rukmini Devi

Arundale, E. Krishna Iyer, and T. Balasaraswati, who sought to preserve

the dance as cultural art.[4]

This period marks the first major de-ritualisation - dance was removed

from temples and redefined as a classical art form suitable for middle

class, nationalist, and educational contexts. Bharatanatyam became a

performance art that represented India's spiritual heritage but within

secular spaces such as auditoriums and academies.[5]

Re-contextualisation in the Modern Nation-State

After India's independence, Bharatanatyam underwent

institutionalisation. Institutions like Kalakshetra (1936), Sangeet

Natak Akademi (1953), and numerous university departments turned the

dance into a pedagogical discipline.[6] The guru-shishya parampara

was adapted into formal classrooms and degree-oriented programs.

This re-contextualisation aligned Bharatanatyam with nationalist ideals,

positioning it as a marker of India's ancient moral and cultural ethos.

Upper caste, educated women became its new custodians, distancing

themselves from the devadasi lineage.[7] Yet, this nationalist revival

contained a contradiction: while the rhetoric of spirituality persisted,

the ritual function disappeared. Margam performances became codified,

audiences secularised, and the focus shifted from divine service to

aesthetic presentation. Bharatanatyam thus emerged as a purified emblem

of cultural pride - sacred in rhetoric, but secular in essence.

Globalisation and Diasporic Re-contextualisations

By the late 20th century, Bharatanatyam had entered a new phase - its

globalisation. Indian diasporas in the United States, United Kingdom,

Singapore, and beyond began establishing dance schools, festivals, and

competitions. Here, Bharatanatyam served as a marker of cultural

identity, especially among second generation Indian youth.[8]

This diasporic re-contextualisation involved a delicate balance between

authenticity and adaptation. For many, learning Bharatanatyam became an

act of reconnecting with ancestral roots. However, global exposure also

led to creative hybridity - fusion with ballet, contemporary dance, and

multimedia performance. Artists like Anita Ratnam, Malavika Sarukkai,

and Aparna Ramaswamy have explored Bharatanatyam through feminist,

intercultural, and experimental lenses, expanding the language of the

form without losing its grammar.[9]

Globalisation thus redefined the performance ecology: audiences became

multicultural, narratives became political, and performance spaces

expanded from cultural halls to international biennales. Bharatanatyam

ceased to be a solely "Indian" art and became a transnational aesthetic

language.

Digital Turn and De-ritualisation 2.0

In the 21st century, digital technology has ushered in what can be

termed De-ritualisation 2.0. Social media platforms such as YouTube,

Instagram, and TikTok have democratised Bharatanatyam's reach, enabling

dancers to build global audiences without institutional gatekeepers.

Short-form videos, online classes, and cross-border collaborations have

redefined performance time, space, and spectatorship.[10]

The temple sanctum and theatre stage have been replaced by the camera

frame; divine viewers have been substituted by algorithms and online

followers. While traditionalists lament the perceived loss of depth and

sanctity, digitalisation has simultaneously enhanced accessibility and

innovation. Online archives, virtual workshops, and interactive

platforms have extended Bharatanatyam's presence beyond geographical

limitations, transforming it from an elite art to a participatory global

practice.

Yet, this transformation also raises questions:

1. Does the digital aesthetic dilute the meditative core of Bharatanatyam?

2. Can algorithmic visibility substitute for aesthetic discipline?

3. What happens to rasa and bhava when mediated through screens?

These questions underline the tension between preservation and innovation - a central theme in the new ecology of performance.

Gender, Body, and Politics in Contemporary Context

Another major axis of re-contextualisation is gender. In recent decades,

Bharatanatyam has become a powerful medium for feminist and queer

narratives. Artists like Navtej Johar, Pavitra Sundar, and Ananya

Chatterjea have used the form to question patriarchal, caste-based, and

heteronormative hierarchies within the classical arts.[11]

The devadasi body, once erased through reformist modernity, is now being

reclaimed through research and performance. Choreographers revisit

archival texts, temple iconography, and oral histories to critique the

Brahminisation of Bharatanatyam.[12] This re-contextualisation is not

merely aesthetic but deeply political - it restores multiplicity to a form

long idealised as singular and pure.

In this light, the 21st-century Bharatanatyam dancer is not a passive

inheritor but an active negotiator of meanings, identities, and power

structures.

Performance Ecology: A Living Network

The term performance ecology aptly captures Bharatanatyam's current

condition - a dynamic network of spaces, technologies, ideologies, and

bodies. The ecology includes:

-

Institutional spaces: academies, universities, and cultural ministries.

-

Independent spaces: festivals, residencies, and experimental collectives.

-

Digital spaces: YouTube, Instagram, virtual workshops, archives.

-

Global networks: diaspora schools, international collaborations, cross-cultural projects.

Within this ecology, Bharatanatyam survives not through static purity

but through adaptive vitality. Every new context - whether ritual,

national, feminist, or digital - adds another layer of meaning.

Thus, the de-ritualisation of Bharatanatyam is not a loss but a

transformation. The sacred has not vanished; it has migrated into new

forms of devotion - devotion to art, identity, and self-expression.

Conclusion

The trajectory of Bharatanatyam reflects a continuous dialogue between

the sacred and the secular, the traditional and the modern, the local

and the global. De-ritualisation did not strip the dance of its essence;

it released it into a wider field of cultural negotiation.

Re-contextualisation, meanwhile, ensured its survival in new ecological

systems - from temple courtyards to digital reels.

In the 21st century, Bharatanatyam stands as both archive and

innovation. It carries the memories of ritual while embracing the

immediacy of contemporary media. Its ecology thrives on

contradiction - discipline and improvisation, devotion and expression,

heritage and futurity.

Ultimately, Bharatanatyam's power lies not in its static preservation

but in its ability to evolve without erasing its soul. The dance that

once embodied divine dialogue now performs the pulse of a globalised,

connected humanity - a living testimony to the resilience of art across

time and transformation.

References (for footnote sources)

1. Meduri, A. (1996). Nation, Woman, Representation: The Sutured History

of the Devadasi and Her Dance. In J. Desmond (Ed.), Meaning in Motion:

New Cultural Studies of Dance (pp. 270-297). Duke University Press.

2. Kersenboom, S. (1987). Nityasumangali: Devadasi Tradition in South India. Motilal Banarsidass.

3. Soneji, D. (2012). Unfinished Gestures: Devadasis, Memory, and Modernity in South India. University of Chicago Press.

4. Ibid.

5. Meduri, A. (2008). Bharatanatyam as a Global Dance: Some Issues in

Research, Teaching, and Practice. Dance Research Journal, 40(2), 29-49.

6. O'Shea, J. (2007). At Home in the World: Bharatanatyam on the Global Stage. Wesleyan University Press.

7. Meduri, A. (1996), op. cit.

8. Srivastava, A. (2018). Performing Identity: Diasporic Negotiations

through Bharatanatyam in the U.S. South Asian Popular Culture, 16(3),

251-263.

9. Ratnam, A. (2010). Transmuting Tradition: Contemporary Expressions in Bharatanatyam. Nartanam, 10(4), 12-18.

10. Rangarajan, S. (2022). Dancing with the Algorithm: The Digital

Mediation of Classical Indian Dance. Asian Theatre Journal, 39(1),

92-112.

11. Chatterjea, A. (2004). Butting Out: Reading Resistive Choreographies

through Works by Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and Chandralekha. Wesleyan

University Press.

12. Johar, N. (2015). Dancing the Other: The Politics of Gender and

Caste in Indian Dance. Performance Research Journal, 20(6), 45-54.

Dr. Amrita Sengupta Dutta is a scholar, performer, and Guest Faculty

in the Department of Dance at Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata. A

Ph.D. holder and UGC-NET-qualified academic, she has served as a Senior

Research Fellow at RBU. A recipient of the National Scholarship from the

Ministry of Culture and a B-graded artist of Kolkata Doordarshan, Dr.

Sengupta Dutta has authored three books and numerous research papers on

Indian dance and culture. She is currently engaged in a research project

funded by the Ministry of Culture, contributing significantly to the

preservation and evolution of Indian performing arts.

Post your comments

Pl provide your name along with your comment. All

appropriate comments posted with name in the blog will be

featured in the site.

|