|

|

|

|

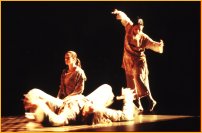

Mark Taylor talks to Lalitha Venkat about creating DUST with Anita Ratnam Nov 24, 2002  In April 2001, Indian dancer/choreographer Anita Ratnam and American choreographer Mark Taylor combined members of their companies to create DUST, a 30-minute work with original music by composer Alice Shields. DUST was the culmination of a three-year period of dialogue and experimentation between Ratnam and Taylor focusing on the kinetic and esthetic potentials of mixing traditional Bharatanatyam and contemporary post-modern movement forms. Mark Taylor (Artistic Director, Dance Alloy) is internationally known as a choreographer and teacher of contemporary dance. He has received Choreography Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and a Creative Achievement Award from the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust. In August 2000 he received the Pittsburgh Magazine Harry Schwalb Excellence in the Arts Award. Taylor has choreographed and taught at the American Dance Festival and the Bates Dance Festival, as well as at festivals in Estonia and Bulgaria. He has taught widely as guest artist at colleges and universities, and from 1986 through 1991, was a dance faculty member at Princeton University. He is a certified practitioner and teacher of Body-Mind Centering®. As artistic director of Dance Alloy in Pittsburgh, PA, Taylor's interests have included intercultural collaborations; work with community casts, and the development of movement generated from techniques of embodied anatomy. In a 3-city tour of India, DUST will be premiered at Hyderabad on November 30, followed by a performance on December 3 at The Other Festival in Chennai, and at Delhi on December 6, 2002. How did DUST happen? One of my assistants at Dance Alloy heard Anita Ratnam speak at a conference in New York. Bill Bissell was very helpful to me over the years in helping me develop my inter-cultural projects and he suggested that we invite Anita to see one of the projects I had done with some Hawaiian artistes. So, Anita came to Pittsburgh, saw the performance and we began correspondence over a possible collaboration. In 1999, I was able to invite Anita and 2 of her dancers for a 2-week residency. At that point of time we had no intention of creating a work. Our dancers learnt some basic Bharatanatyam movements. Anita and her dancers learnt contact improvisations in modern technique. Out of that exchange came the idea to collaborate to create a work. The thing that intrigued both of us was the dynamics of the kinetic. The most interesting thing was several studies we did that combined Bharatanatyam steps and our kind of movement process. We felt we could use the richness because the Bharatanatyam movement was vertically oriented, very spatial in its directionality, used very precise and clear lines and the rhythms were fantastic. Our movement is all about working through space with a horizontal thrust of the body. When we combined the two, there were some very exciting movements. I came to Madras in December 1999 because I felt I needed to learn more about Carnatic music and dance. I saw many shows and through discussions with Anita Ratnam and others, I felt I had enough information about this culture and felt like an informed visitor. Anita already had a good grasp about the kind of work that Dance Alloy does, so the learning for her was easier. After being in Madras, we agreed to look for a theme for a work and to commit to our own companies spending time together. Out of that commitment, DUST happened. How did you arrive at DUST as a title? DUST was taken from the writings of Alexandra David-Néel who called Dust the principle of vibrations, the very centre of existence, of being. In other words, we are all dust! Dust is the universal constant. We talk of dust through out space. Anita and I were both interested in exploring the Tibetan ritual in tantric Buddhism called Chod, a practice in which the practitioners sit in a graveyard and meditate over the bones of deceased people, meet the demons, which hover around the bones. The images in Chod gives oneself away in the most graphic and simple illustrations, like chopping of limbs and throwing them away and in the spiritual way, it is giving up oneself to the universe. I was inspired by Alexandra David-Néel's writings and also by her remarkable story. She was the first European woman to enter Lhasa and study Tibetan Buddhism at the source in a lifelong process, a difficult thing for anyone to do, especially a woman. How did you work out the choreography process? I worked with a composer Alice Shields who was a wonderful choice for this piece She's not only a very experienced composer of electronic music, she has also studied Indian music forms, like jathis and thillanas. We wanted to look at the form of the thillana, essentially not to create a thillana as in Bharatanatyam, but look at parts of it, the devotional part, to look and see how we can go to the root of what it means, look at it from our perspective as westerners. We proposed this to Anita and she thought it was a good idea. I had a sense of structure, lot of music and sound was established. When the dancers arrived without Anita, we started work with the dancers contributing their own ideas and movement material. So when Anita arrived, we had the rudimentary structure, which we then refined. This is the first version we performed in May 2001. There were subsequent versions with more refinement, answering questions that cropped up. What we will perform now is the second draft post September 11. How did the September 11 disaster affect DUST? We were very deeply affected because we had planned to come to India this time last year. Due to airline cancellations, we were unable to. More importantly, in the US, we were living together as a community before that happened. In retrospect, it was a pivotal moment for our culture, it turned everything. Life is not the same since then. Being together at that time as a group was a bonding experience for us, I think that made the piece richer. We experienced emotional upheaval, including fear, sorrow, anger, even love. What other images contributed to the making of DUST? It is important to emphasize the collaborative nature of the project. Anita and I are certainly the people who guided the project. Alice Shields contributed to the structure of the project, the dancers to the physicality. Costume designer Myra Bullington looked at photos of Tibetan monks and peasants and based on that came the colour palette and patterns. The original lighting design is by Barbara Thompson. It emphasised a 10' square area of space, which becomes alternately an altar, a plain space, a kitchen, a porch, a sacred space. The lighting definitely contributed a sense of mystery. Are you happy you finally made it to India? Yes, I feel that to perform here is a necessary part of the project. It's been quite exciting to perform in the US. But I feel it's very important in an inter-cultural process to have the reciprocity. We need to hear from the Indian audience what their perceptions are. Have you done other cross-cultural collaborations? Yes. The major one is the Hawaiian project I mentioned earlier, a project I created over a span of 2 years in the Caribbean with a calypso singer from Trinidad, and I also worked on a project with an Indian classical dancer. You are a teacher of Body-Mind Centering. What exactly is that? It is a technique of 'embodied anatomy', and what that means is, you learn to initiate movement and sound specifically for each body system and tissue. It has wide applications. It can be used in creative process and also as a therapy for children with development problems. How would you describe your work? The bulk of my choreographic work has been with movement exploration, inventing new vocabulary for each dance. So, it's a process that has to do with accessing the body and mind together and experimenting on new themes or new interests with what movement arises. In a way, that's why I gravitate towards inter-cultural collaborations because I'm interested in things I don't know how to do. (November 24, 2002) |