|

|

|

|

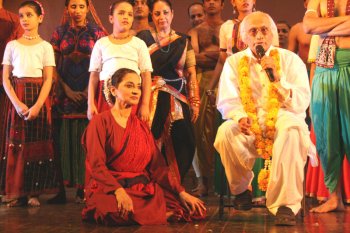

Guru Ghanshyam - Sheema Kermani, Pakistan e-mail: tehrik@gmail.com February 17, 2011 (Guru Ghanshyam was interviewed by Sheema Kermani in April 2010 for the monthly Herald magazine of May 2010)  Ghanshyam Sahib you were a student of the great pioneer of Indian Dance, Uday Shankar who had set up a Cultural Centre at Almora. Please tell us how this came about. It was while I was a young boy, perhaps about 12 or 13 years old, studying in Bombay that my father's friend Professor GN Mathrani who was a Sindhi gentleman and a professor of Philosophy and Psychology became my guardian and brought me to live with him in Shikarpur, Sindh. This is of course before the partition of India - must be around 1936 or so. Here I spent a great deal of time outdoors and close to nature. Professor Mathrani saw and recognised in me a spark for dancing as I would climb trees and skip and jump and dance around outdoors, I was not really interested in going to school. He had heard about the legendary Uday Shankar who had recently set up this Centre for Dance at Almora and he decided that I should learn dance. He wrote a recommendation letter for me to Uday Shankar and on the basis of the recommendation I was asked to come and give an audition before I was given admission. I remember that I had to wait till I was 16 years old before I joined the Dance School as that was the minimum age of admission. I spent four years at Almora. What was it like at Almora- what were you taught there? Well, classes would begin at 7am. There would be a general class which comprised of 40 to 60 students. Shankar Dada himself would give a lecture everyday in the general class. Then he made us do improvisations - sometimes he would make us walk across the classroom which was a huge room - 60 feet by 40 feet. He would say, "Feel the ground that you are walking on; imagine yourself in different situations, imagine everything around you and recall all from birth to now." He made us do these exercises so that we could develop our imagination. Imagination, improvisation and creation were the cornerstones of Shankar Dada's teaching. Then we would have the dance exercise classes. We were taught different movements, different styles. We would have breakfast at about 9 a.m. Later we would be given an hour to rehearse all that we had learnt. I remember that all the time a teacher would be observing us and would suddenly ask us random questions. This he did to basically ascertain our level of alertness. So it was not just a dance school, rather it was an entire system of education. Yes, you are right. We were expected to immerse ourselves in the dance and the movements so completely that it became a part of our system. Shankar Dada was a great artist and a wonderful performer. He was also an incredible teacher and taught us to put expression into all our actions, movements, and then create further actions- it was almost like weaving pearls into a necklace. How did you happen to come to Pakistan? A very dear friend of mine from Calcutta, who was in the film business, George Malik, had obtained a large amount of money to produce a film in Pakistan called 'Funkaar' and he asked me to come down to Pakistan to do the choreography for his film. So I came to Karachi to work with him. The film never got completed but this is how I came to Pakistan. And why did you decide to stay on? While I was working on the film - it was around 1952, I had a performance and Mr. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy who was the Prime Minister of Pakistan at the time happened to be the chief guest at this show. I had known Suharwardy in Calcutta where he had been my neighbour when he was the Governor of Bengal. He recognised me and he invited me to stay on in Pakistan, he suggested to me that I start a Dance Centre in Karachi. He was a great patron of the Arts and he felt that Pakistan needed artists and dancers and art institutes. Did you have any problems in those early days in Pakistan? Well, not really, except for certain occasions when some small petty officials of the bureaucracy would sometimes give us trouble. You see, I did not have a passport in those days and these officials would turn up and ask to see my passport. And why would they do that? Oh, basically of course to make some money. I went to Mr. Suhrawardy and complained to him and he immediately took action and demoted those officials. He told me to remain calm and unafraid and was kind enough to depute a police guard outside my place. And that's how I stayed on in Pakistan. Had he not supported me I would have not been able to stay back. Mr Ghanshyam while you were living in Pakistan and right up to the 1980's the Government and the Ministry of Culture used to give you funds. Besides this, the industrialists and businessmen would also give a lot of financial support. I remember the brochures printed for our performances in those days would be full of advertisements. Then during General Zia ul Haq's time all government funding for cultural activity ended and so did all other support. Now it is a very tough task to get any kind of funding for culture- especially dance- one has to literally knock on so many doors and often return empty handed. I feel that when the state and the government does not patronise the Arts then others, philanthropists and industrialists also do not give their support. However, tell us about the time when you and your family started getting threats and you were forced to leave Pakistan. That was indeed a very difficult time for me. First the funding became erratic and then it stopped. I would write to the Government, to the Ministry, to send me funds but they would not respond. I didn't have any connections, nor did I know any ministers, so I did not know how I could continue without funds. Then the conditions started becoming really bad. I would hear shouts and abuses outside my house, they would scream at me saying "Aye Hindu ka bacha yeh naach gana band kar." I would not know what to do! I started becoming very frustrated and then sometimes I would react with defiance and say to them, "Yes I am a Hindu- yes I sing and dance, do whatever you want - let's see how you can stop me!" My wife Nilima would be very afraid for me. She feared that someone would kill me. It was a terrible, terrible time. This kind of harassment started soon after General Zia came into power in 1977 and you and Mrs. Ghanshyam left in 1983, the year when Zia brought in all these Anti-Women and Anti-Minority laws like the Blasphemy law. Tell us, how did the problems start that made you leave Pakistan? As I said, I started getting threatening letters. Then my house which was also my teaching centre was attacked with stones. I reported to the police and requested them to help us but they did not. It was my neighbours, my students and my family friends who were kind enough to patrol our house even at night. They were a great source of comfort and help to us but all this stone throwing and abuse did not stop. Yes I remember the writings on your compound wall "Jo bhi yahan ayega naach ganay kay liyay, un ko Islami nizam kay tahat saza dee jayegi". I remember that every day you would have to replace the bulb outside as someone would throw a stone aimed at it. Humm... but it's when they started to threaten my family, my children that I knew that now I had to leave. Luckily my children had started getting scholarships and going abroad one by one. Mr. Ghanshyam you know the same thing happened with me in the 1980s. I started to get threatening letters that said that I am spreading Hinduism and Indian culture and that they will bomb my house. But dance is humanist art! It doesn't belong to any religion. It is human action. You cannot stop action, action is dance. If you stop action then you die. (At this point Mr. Ghanshyam had tears in his eyes and became very emotional. We continued the interview a little later.)  I remember the Rhythmic Art Centre where I used to come as a child - it was a very vibrant place, parents would feel comfortable dropping off their kids... Yes, we tried to create a family environment. The first teacher at the centre that we hired was Ustad Shabbir Hussain, who taught music. Even though it was a small house, we had set it up in such a way that several classes would take place. In one room my wife would teach dancing to the younger kids. In another there would be a sitar class going on. In another, singing. Then we would also have lots of shows, performances, do dance dramas and I would ask my students to help me out in set construction. I remember you Sheema doing a lot of painting for our sets and helping make the props etc. Tell us about the time when you put up performances for various dignitaries because I remember that I performed in your troupe in front of Chou En-Lai, the Chinese Premier... President Ayub Khan was very supportive and he often sent me and my troupe all over the world to perform. Even Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, when he was the foreign minister would invite my troupe to perform in front of the ministers and dignitaries who were visiting from other countries. You left Pakistan in 1983 and went to the US. How has it been there for you? Once we shifted, we set up a teaching place and I was surprised to see that many Americans were keen to learn dance but relatively fewer Indians and Pakistanis. When I approached the local Indian and Pakistani population they informed me that they were there to earn money not to spend it. I joined University of Indiana in Fort Wayne as a Professor of Yoga. I enjoyed my teaching stint there but soon realised that American students do not want to put in the kind of effort that is needed to learn our kind of classical dance. Mr. Ghanshyam, after you all left Pakistan I took over and started teaching dance here in Karachi. Now I have been teaching since 1983 and I really want to set up an Institute, but there are so many obstacles... Yes, Sheema, I have told you several times that you should set up a Centre. I don't have that much long to live but I truly want to help you in this venture and I want to impart whatever I can to you and your students. Yes, I know Mr Ghanshyam, but you see the situation here is very tough now - for a start where and how do we find the land to set up such a place. I have been trying for ever so long. Since after you left, my aim has been to set up an Institute but it all seems so difficult. Why doesn't the government help you? You have a lot of courage, my dear - I really appreciate what you are doing and I know that you need a lot of support! I wish I could do something to help set up this Institute. When we were learning dance from you, you taught us so many different styles and forms. We learnt Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kathakali, and Manipuri - basically we learnt various classical dance forms. Now there is the fashion to say that so and so is a Kathak dancer and so and so is an Odissi dancer and so on and so forth. What is your view about this trend of categorisation of dancing? I believe that classical dance is classical dance. You see, the layperson doesn't know what classical dance is, that is why I never taught my students one particular dance form. They learnt all forms of classical dance from me. The aim was to draw from all these forms and evolve something called Pakistani dance. I was leading all my students towards finding the dance of their country. I myself travelled to Sindh and Peshawar and did research on Ghandhara and Mohenjodaro. All these dancing artefacts belong to you. I would say that you should take pride, do research on them. In Pakistan, people do not know what their culture is. You once told me that when you used to represent Pakistan how warmly you would be received in other countries and also how you used to get so much appreciation within Pakistan. But you know when I have performances here even in front of government functionaries, they treat us and all performers like their servants. I wonder when that will change? That's because now there is dirty politics and unfortunately it looks like this will never end unless people like you come into power. You see in those days there were people like Raja Tridev Roy, who was a Minister for Minorities as well Minister for Art and Culture; he was a very cultured and educated man - truly a gentleman! I remember that once in a conversation, he asked me, 'How long do you think you can survive here?' I had laughed it off and said to him, 'Well, as long as I can!' But you see I had to almost run for my life! |