|

|

|

|

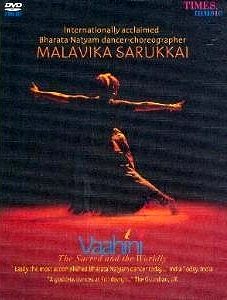

I don't call my work a performance. I call it an experience: Malavika Sarukkai - Veejay Sai, Bangalore e-mail: veejaysai.vs@gmail.com May 11, 2010 This interview was first published in artindia.net It is not often that someone easily casts a spell on you and it stays like a hangover for a long time after her dance performance. In south India, every other house has either a dancer or a musician undergoing tutoring even as you read this. While that is a wonderful idea and sounds encouraging for the future of performing arts, very few of these artists manage to make it to the stage and sustain a successful career. And a fewer worth mentioning when speaking of people who have done justice to represent their dance forms. After having enthralled audiences across the world for the last few decades, Malavika Sarukkai now takes the illustrious position of being one of the finest exponents of Bharatanatyam. She began her studies in dance at the age of seven training under Guru Kalyanasundaram of the Thanjavur School and Guru Rajaratnam of the Vazhuvoor School of dance. She studied abhinaya with Guru Kalanidhi Narayanan and the Odissi dance style with Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra and Guru Ramani Jena. Malavika has also collaborated with her sister, the well-known poet and novelist Priya Sarukkai Chabria. She was touring the launch of her new DVD titled 'Vahini' released by Times Music. On first impression, the double-DVD set is indeed a delight to view and it surely is a must-have if you have been a connoisseur of Indian dance. It has a wonderful eclectic assortment of productions done by Malavika over the years. It serves as a great classroom educative viewing for students of dance and is one of the best examples to showcase how Malavika has shown the inter-disciplinary nature of dance. Working with space, movement, sculpture, tradition so on and so forth, she breaks the myth that Indian classical arts are highly rigid. In an exclusive interview, Malavika Sarukkai shares her passion for life and how it couldn't be entwined with anything else but her art.

Can you tell us how 'Vahini' came about? This DVD was an idea that came out after much thought. For many years I would travel all over the world and perform. I had audiences who would come and tell me that much as they loved my performance, they didn't have anything to take back home. So it was this need to give back a slice of my art that came about in the form of a DVD of this nature. I was supported by a very dear friend of mine who encouraged me to do it. It costs money to make a DVD, it doesn't come easy. And the other thing is, it comes across as a very different aspect of dance. It is one thing to dance in a theatre space performing in front of an audience. The whole concept of putting it on to a visual medium and recording it is different. For me it is quite a milestone because it makes dance available to viewers and in a sense is dissemination of what dance is about. I am glad I did it. I'm very happy I've been able to give a cross section of pieces in this DVD. So it's not just the maargam or the traditional repertoire that I do, I've also a padam and other structures of choreography in it.  You are known for your classical dance but you have also choreographed new productions of contemporary dance with a strong Indian idiom. How do you respond to working differently as a dancer and as a choreographer? Traditional dance pieces have a structure and there is almost a habit in it. You follow it and of course you can be very inventive about how you interpret it. There is vast scope for that. But I think when you do a completely different choreography, it's like walking into a room where there is complete silence and there is nothing on the canvas, you look at it and ask 'where and how do I start? What do I want to fill this canvas with?' I think it's almost a kind of intuitive process. At least my work is a lot of intuition on how I feel the movement. There is cerebration to it. There is a concept. There is an overall structure. Like I did a piece called 'Sthithi-gathi', which is stillness and movement. That came about because I've seen a lot of sculptures and seen the inter-relatedness between sculpture and dance in India. Standing close to these Chola bronzes, at the Saraswathi Mahal Library Museum in Thanjavur, you see those bronzes and they live! They still resonate with energy! You can walk around them, look at them and still there is that beatific smile, that grace of the arms, the length of the body, the torso and so on. It's absolutely a living presence. And I watched them closely and wondered what it is that makes them so lively. I think it's the energy of stillness and movement which is the intent with which the sculptor has actually created the bronze. This creative process is also very meditative. At least in India when we are talking about spiritual, it is a seed which lies within choreography. My kind of choreography is very rooted in the sacred. Seeing those bronze sculptures one feels there is a movement from within. You can sense the movement. So, in a choreographic piece like 'Sthithi-gathi,' I was aware about the fact that even if I pause, there is an energy radiating from within. And these things are very much to do with how the mind participates in dance.  One of the arguments that face choreographers is that their work is all highly engineered and it is bereft of any creative spontaneity. In a pure dance performance as in Nritta, we have rhythm, structure, taala and things we work with. The spontaneity or the freshness happens when the movement is performed with an acute sync of mind and body. I am speaking of dance technique here. When the body and mind are in complete sync, even if you've practiced it fifty times before that just to get it right, it comes to life on stage with newness. This comes when the mind sharpens movement. The intent of the mind, what I am thinking when I dance, when I stretch my arm out in space and so on is important. Maybe I could sum it up in saying it's a form of 'mindfullness.' Be it abhinaya or nritta, it is this 'mindfullness' that keeps it alive and live in the present. I have often talked about my dance saying that it is a language of the present tense. People often say classical dance means to speak of the past. I say it's in the now. In the today. Making of that movement on stage is re-creating it, rather than imitating it. There is so much riyaaz and sadhana in classical dance, people often tend to see it as something that is not growing or living but is stagnating. But living dance, I know it is not that way. I would almost call it meditative. And that movement has to be created every time. It cannot be commanded, imitated or simply called upon. I can't say I did it last week this time, so now come again. That cannot happen. It is a movement you make in the moment. Now that is what gives me, as an artist, a continuous freshness in my dance. While purists question the importance of the outcome and value of choreographic performances, it's foolish to deny that choreography in turn has managed to sustain the interest in dance amongst newer audiences. Is the process as important as the outcome? The process is very important and there is a lot to process but in art, as in classical dance, the moment happens out of anywhere. It is created. There is a lot to do with process, technique and cerebration. There is a lot of precise and clear thinking in every choreographic piece. The mind plays a huge role in my work. My work is not about huge concepts which have to be explained a lot. It is about deep-rooted concepts which I hope I keep the essence of it. Frankly speaking, I don't even call my work as performances, in the end. I call them experiences. I reworked that for the last few years. I decided I am not going on stage to perform. I have done that earlier. Now I go on the stage to experience something through my art. With the sadhana I have done for so many years, I find I can experience something. Process has thinking to it but there is also tremendous freedom within it. We normally say tradition OR change: that big word 'Or' which we put in the middle to demarcate. But I've always looked at it as tradition AND change. It's a continuum. Tradition doesn't exclude change. I think an artist's responsibility is to adapt and that's why we have continuity in this country. We are given the freedom and responsibility as if saying 'please now this is your tradition, see how you continue it.' As an artist, if I look at the last twenty-five years I have done choreography, it's because I've seen the potential of change within it. When I can keep to the classical grammar and identity, and within that, especially because I see it as a language, I have never seen Bharatanatyam as a 'style' of dance; I see it as a language I speak. So when I look at it like that, I also realize that I can speak it in different ways. I can make new words, new sentences, and rewrite, rephrase so on and so forth. Those people, who want to see Bharatanatyam as a maargam, should by all means go ahead and do it. When I see maargam being presented, which we see very little of now, I see it as 'period.' It has its own reason, beauty and place to exist. For me it's different. I think I've been too much of a thinking and questioning artist. I have looked at maargam, seen padams and jaavalis and things written for courts and kings; it had a certain context under which it flowered which was very meaningful at that time. But I see this time and ask myself what is meaningful. For me, the now is meaningful. There are audiences who like to see maargam because there is a certain comfort and familiarity for them to go back to it again and again. It can coexist for those artists who want to perform it and those audiences who want to enjoy it. But for some other artists, and I fall into that category, there is a great need to explore the medium. There is a need to find new meanings, challenges, perspectives and that's why I have seen it more as a 'language' of dance. And when I say language, there is so much possible. One of the biggest banes of dance recitals has been that many dancers often come on stage with a hangover of their older performances. The same movements and structures get stereotyped, consciously or unconsciously, on stage. How does one avoid this sort of over-lapping of creative work? That is something I work on very astutely. I don't want any of these spillovers. Just because I have done it before, I wouldn't take the same thing, smoothen it out into another piece and then say I have done a new performance. Over the last twenty-five years, I've been saying that each piece has its special quality. I have been very determined to give each piece its exclusivity. So I had to actually work very hard on myself. That demands a lot from yourself because you are not going to fall into a 'repeat' syndrome. Every time you have to pull out of yourself, something else which that particular choreography demands. I have been very clear that I want to do that. I am very hard with myself. You will hear a lot of stories of how Malavika akka dances for many hours and she also expects her musicians to rehearse for many hours. Yes I do. It all is true. Otherwise you can't do justice to the piece and give it that uniqueness. Some time ago, I choreographed a piece on Devi 'Mahishasura mardhini.' Devi was a subject I kept far away from myself thinking I don't know if I can handle it. I was not ready to handle the concept of 'Shakthi.' I was working with NCPA and PN Goswami and before I knew it, I realized I had decided to work with it. If you see that piece, it is entirely different from anything else I have done. I work with Bharatanatyam but there are in-flows. I am distilling, observing from life inside me and this slowly becomes a movement in my choreography. It is like the underground river process. You know you can't see it but there is a lot of movement happening. So I demand a lot from myself. Every artist, some way or the other, gets influenced by experiences life bestows. Sometimes good, sometimes bad, these experiences leave a long lasting image on one's thinking and philosophy which slowly reflect in their art. How have your own personal experiences shaped your work? Shringaaram was always a part of Bharatanatyam repertoire; all those nuances of padams and jaavalis and so on. I used to really enjoy my classes with Kalanidhi maami in the late 1970's and 80's when I trained with her. And that time it seemed to be such a fabulous world filled with the filigree of shringaaram, man-woman relationships, and all those unseen, would-be-seen, perhaps-seen, wanting-to-be-seen movements which was like a huge high for me. You know life looks very different at that stage. Then a few years ago, I lost a dear friend of mine who used to do music for me. As long as she was there, it was like 'she is there!' and one day she wasn't there. That affected me a lot. The sudden absence of a person makes you realize what he or she really means to you. At that time, I was doing this story, the journey of a courtesan called 'Kashi Yatra.' I had done the first part after which my friend passed away. I had to deal with this emotion of death. What is it? What is loss? So I found that in the story and choreography I was building up, I created a scene where the child died. It just happened. I was trying to, through dance, confront this emotion of loss, grief, desolation and the pain of death. Which was a sudden thing… that was not a part of the repertoire at all. No maargam has anything on death. I did that because after a certain point, life was not all about shringaaram but all these different facets to it. Then I also did 'Astam gatho ravi.' I have done something from the Mahabharata which speaks of war and death. The whole meaninglessness of war. Gandhari's lament when she sees this devastated battlefield before her, Abhimanyu's death and Uttara's lament and various other pieces. You can't make sense of it. All you can do is put it forth, through art and ask the audience 'why.' Images stay with me in my mind. I remember doing this Gandhari's lament. At that time, there was this big attack and a blast in a school in the Soviet Union and there were all these little school children who died. The picture was that of a soldier who comes out holding the body of a dead child with the most ghastly expression on his face. You looked at it and thought, is this the world we live in? Is this the horror and pain of it all? And I think through art, if one can bring about a deeper reflection on it, rather than just an agitated response. I think art works through the verticals. I have done pieces on environment. I have done so many pieces on trees. I love trees. I really feel that they are presences. When I say the language of dance, I need to empathize and find out how a tree feels. I don't know. I have to find out through dance. How does a sap feel rising in the tree? How do I capture that movement and that energy when the sap goes into every branch and twig, how do the leaves feel twirling in the breeze, what is it for a tree to feel birds on its branches, so it's a passionate empathizing which I do to re-create. Having worked closely with personal ideologies which reflect in your dance, your performances has often left audiences thinking about serious issues to act upon. Can performing arts like dance still have a political ambition without making their metaphors sound like escapist routes into creative fantasies? I don't think classical arts are meant to be reactive. I think it can bring to you issues which are very urgent. But since art speaks through the metaphor, like I'd like my work to speak through the metaphor, I don't want to make it black and white like a newsprint; I don't want to do literal things like murder, rape and so on. I don't want the literal. When something is subtle, for one when something is more Natya-dharmi and not Loka-dharmi, the metaphor has different ripples on stage. Each one can read it differently. It gives much more scope for the understanding of what is happening. The very literal is something that I move away from. I would deal with issues which I feel I can relate through my work and a certain poetic stylization. Stylization gives it a much larger perspective and range. I think there are ways of making statements. I always ask people not to just look at dance but look into dance. There is a whole lot of meaning and enrichment you can find there. Give yourself the time and space in your mind. Like I have adapted my dance to it, be it an environment issue or something else. Someone who followed my dance for a long time came up to me and said that my dance reminded him of the singing style of Pt Kumar Gandharva. It sounded nice to get this outside perspective for me. But I wanted to know more and how? He said that when Kumar ji used to sing, he always held his left fist close to himself, closed, while his right hand, he threw open into the air and gestured as he went about his concert. He said it was like holding your own tradition and classicism close to your heart and with the other hand you let yourself roam, find that freedom, and I thought that was very true. This person had gone into my art and studied it and understood it this way which even I couldn't sense or verbalise about my art. I believe in the infinite meaning that the classical can afford. One part of me has high reverence for the classical while the other part of me is highly explorative. I think what I am doing is balancing both. I think you find the freedom if you find the roots. A dilemma that artists often face is how to transcend these strong perceived notions of what is tradition and what is modern. Where does the thin line lie and can it afford to be easily blurred? What is easier to find, the roots or the freedom? I think you first have to stay with the roots. You have to really root deep and firm. You also need to root with a certain utsaaham. And it cannot be a dishonest utsaaham. When you do this for a period of time, you suddenly start finding freedom. It is almost a simultaneous process. It takes a while for one to be rooted physically and emotionally. If you can celebrate every moment of the uniqueness of tradition and find the joy in it, in the flip side it opens up a space of freedom. I am speaking about something which is very internal here. When you look back at tradition you realize there is so much scope for more. Like I said when I was doing 'Devi,' I just realized there were so many new movements I discovered. Even I was surprised by this. There is impulse, intuition and there is also a great amount of technique. I think body-intelligence is a great part of an artist's life. Sometimes when I see students standing in the first position about to dance, I tell them you should feel what a swimmer feels when they are about to dive. You know that moment when every cell in their body is absolutely alert and their body and mind are in total sync with each other, now that is dance! And every moment in dance must be like that! If you see an instrument and see the thanthi, you must question what is the thanthi of my body and what music shall I make. To find out where is that thin line is your personal sadhana. It is a very fierce sadhana. You have to keep that thanthi of yours stretched and tuned to that very fine tension which produced the best music. Trust me, there is no set direction to find it. Just work on yourself. You will know when you have found it. It is only through that personal experience that you'll know. Many times musicians, dancers, painters and all others in the arts often get lost or sometimes improve due to the reaction they face in their own work. Sometimes from audiences and fans, some other times from healthy critics. Being influenced by the reaction to one's work has often made the turning point in the life of many artists. Oh yes! Over the last several years people have responded in varied measures to my art. One person told me how he saw the big bang theory in my 'Sthithi-gathi' performance. He was a scientist so obviously his thought process was very different. Or I have people who come backstage and tell me how they felt after they saw a performance. Sometimes I have people who just come and hold my hands and don't speak anything. Such audience responses do matter immensely to an artist's fine tuning. I know how art affects them and I am also equally humbled by it. I know that when I am dancing, it is a completely different energy that I am filled with. I also say that when I go on stage, I want to be empty so that I can fill. To feel this energy which is radiating through your being requires a certain preparation. If I get on the stage with my mind crowded with a hundred things about what sponsors said, what is my next program, so on and so forth, I can't get on stage with such a state of mind. You need to clear this debris of thought. I am speaking here from a very personal approach. It might be different for different people. Then when I get on the stage, I am almost calling upon the energies outside to inhabit me. You call up on that energy to radiate within you, transform you and fill you. So my philosophy of dance would be to fill in this space and for this to fill, you must constantly keep emptying. I don't want to be Malavika Sarukkai on stage. I want the dance, not the dancer. Finally on the stage, if I can create dance and people can experience that dance, rather than look at me, my identity as Malavika, that is more important. The audience takes back these resonances; they take back the art with them. I remember I had gone to Zurich after a performance to this wonderful huge house with huge gardens, it was a bright blue cloudless sky, birds were out, and it was a wonderful lazy afternoon and there was this lovely courtyard with green creepers growing around and there was a certain leisure that had descended into all these spaces. In one corner sat this huge Buddha looking peaceful and I was walking around with my friend and we see this huge gong. My friend asked me if I knew how to play that and I never had done that before. She took the striker and slowly went about it and it produced a wonderful sound. The sound resonated all over the space and stopped. But when you put your ear to the gong, the sound was still there in it. At that time I remember my mother was standing next to me and I just turned to her and exclaimed 'Amma! This is art!' I found this to be a lovely metaphor for what art is all about. If I compare the sound of the gong to the external performance and amplification, the sound of it when I put my ear to it is the resonance. It is this resonance that stays with me long after the program is over. That sound of reverberation is Rasa. To get this resonance, all of these steps are necessary - the preparation, the striking, the externally amplified sound and finally the resonance. There is so much wisdom in our lives, it's just that we don't see it. Do you like challenges? I love taking on new things and building new bridges. Sometime ago I had worked on a piece on Hanuman from Tulsidas. Everyone was surprised. I was asked why I was challenging myself with all these new things when I could stick to all those beautiful shringaara -themed performances. But I wanted to see how Hanuman felt the first time he saw Lord Rama, the emotions, the various new movements and so on. It just challenged me to go on to unchartered territories of movement and interpretations. I like collaborative works and I love challenges. What are the major influences in your life? My mother has been one of my biggest gurus and a big support system all through my career. From being my manager to running around backstage to attending each and every performance of mine and evaluating me time and again, she played a major role in my life. At 16 it was my impulse to dance, but it was her decision. She said if dance is going to keep me happy, that is what I must take up. So it has been a great journey. I used to be awed when I was taken to performances by Balasaraswati or Yamini Krishnamurthy. The biggest lesson you have learnt in life? Come what may, keep faith! No matter what people say, applaud, don't appreciate, amongst desperations and frustrations, I would say keep faith! That has what has kept me going. This is what I tell students of dance. It is easy to lose your way around. Just keep the faith! Malavika Sarukkai can be contacted at: malavikama@gmail.com Veejay Sai is a well-known writer, editor and a culture critic. |