|

|

|

|

Three dancers - one poet - Hariharan Balakrishnan, Bhubaneswar e-mail: fabalas02@yahoo.com April 6, 2008 What brings together three eminent classical dancers of different genre on the same platform with the same mission? One poet- Mayadhar Mansingh. And his poetry.

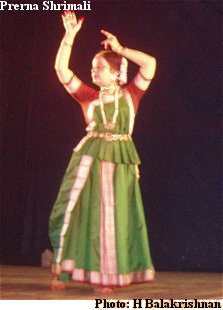

Madhavi Mudgal is one of the finest exponents of Odissi today. Rama Vaidyanathan is a choreographer and Bharatanatyam exponent, at whose dance performances people sit up and take notice. Prerna Shrimali is a Kathak dancer who has been creating waves on the stage for the past few years. All came together to perform to the lyrics of a path-breaking poet of Orissa in the 20th century- Mayadhar Mansingh. The idea of synthesizing the nuance of words in verse in any language as dance - and of different schools at that, sprouted more than a year ago when Mayadhar Mansingh's children talked to these three dancers about the vast array the poet had produced in his lifetime. It was a challenge. Time was short, but a show was held in Delhi in honour of the poet for his centenary. The idea crystallized in the poet's native State Orissa - in Bhubaneswar on 17 February 2008 - one year, three months and three days after the Centenary of Mayadhar Mansingh. Very appropriately, it happened in the presence of the poet's eldest son Lalit, younger son Lalu and daughter Nivedita.    Madhavi, Rama and Prerna were effusive about what they jointly produced in Delhi with meticulous care, immense patience and a genuine going back to being sishyas. The event was all the more remarkable since none of the dancers is a born Oriya. They all say with one voice that dance is a universal language - as is poetry. Excerpts from the free-wheeling conversation…. How did you three come together and produce this unique program? Rama: It was more than a year ago. Mr. Lalit Mansingh approached Madhaviji with the idea of paying tribute to his father Mayadhar Mansingh through interpretation of his poetry in dance form for his birth centenary. The poems were in Oriya, but the three of us representing three different dance styles were to interpret it. It was a challenge. It was a huge exercise choosing the poems since he had a vast body of work. We got great help from Devdas Chhotray in this, and also Kavita Dwivedi who wrote the poems in Devanagari script. It was a wonderful experience understanding Mayadhar Mansingh's poems, which could be visualized in any form of dance. Initially, it was only meetings and brainstorming. After six months of this, we really started working on it and getting ready for the presentation. How many poems did you finally select, and which was the most satisfying as a dancer? Rama: We were going to basically present 5 or 6, and each was fulfilling in its own way. One is Nataraja, and for a dancer it is wonderful to visualize Nataraja. Another was the most famous poem, Ei Sahakara Taley (Under the Mango Tree). In these poems, it is the Nayak (hero) who is speaking, unlike in most other poems where the heroine speaks. This was also a new experience for us. Madhavi, we all know that you had integrated Odissi and Bharatanatyam with Alarmel Valli. Is this the first time you have brought in Kathak for this 3-way integration? Madhavi: This is for the first time that the three dance forms have been brought together for Oriya poetry. Classical dance is so rich and powerful that the challenge was to bring out the essence and beauty of Oriya poetry in all three styles. It was an interesting challenge. Of course, it was originally meant for an audience in Delhi, most of whom didn't know Oriya. That way, we all had the same advantage or disadvantage. Composing music to suit all styles was daunting. In this, we got the help of Sri Maheswar Raut of Delhi to ensure that the nuances of the Oriya language were retained. It was a long process. The process itself was more enjoyable for me than the final product. We learnt a lot by this and are richer in that sense. Of course, we had known each other. But working together for a project like this brings out a different feeling. I don't think this can be explained easily to others. One has to go through the experience to understand. I am sure Rama and Prerna agree. (Both nod in agreement) Prerna, Kathak being based on North Indian languages and dialects, how easy or difficult was it for you to relate to Dr. Mansingh's poetry in Oriya? Prerna: Dance has its own language and it doesn't really matter with which language of poetry you are working. It was quite easy since, basically, it was romantic poetry. Shringar lends itself admirably to dance. Except that in Kathak, it was a bit difficult to use the six-beats. It was somewhat difficult in the beginning, but finally it came out really well. Kathak has a vast repertoire of Nritta and we have many permutations and combination of bols or syllables, and we can compose according to the poetry. So, I never felt it was tough. Rama told me earlier that the poems were transcribed into the Devnagari script and the nuances learnt. What do you think about interpretation of Oriya poetry in Bharatanatyam that is steeped in Dravidian idiom? R: For a dancer, poetry can be in any language. Ultimately it is the language of dance that gives empowerment. I have been born and brought up in Delhi and Devanagari is natural to me as a script. I found no problem at all. M: This combining of different languages and forms through dance is in fact an example of national integration. While political people are trying to keep us apart, this is a manifestation of how Art brings us together. By the way, did you read the poetry of Mansingh translated into English in the book "Ripples of the Mahanadi," at least these poems you are presenting in dance? R: Actually, we saw the book only later. We did read some of the poems in English, but what matters are the different nuances as in the original - the dhwani. The Sanskrit base helped, and the nuances were admirably explained to us by Oriya experts. You said earlier that dance is a universal language. We are not talking about Western dances here. What would you say is the common thread that runs through all classical Indian dance forms? M: The common thread is the raag, thaal and bhaavana. To what extent is dance inspired by religion and the spiritual element? M: Religion as it is understood today is not the kind of religion I know. Maybe spirituality is the right word. That is what inspires and influences dance. The basic Indian cultural traditions - and religion is a part of it - inspires dance, poetry, painting and other forms of Art. Dharma is different from religion, but then that is a different realm of discussion. Of course, these days we are not dancing in temples and treat dance as a secular art form. But the roots are in the tradition. It is the soul of our dance. There is absolutely no doubt about that. P: Dance itself is a powerful language. It does not matter even if a temple or church or any other place of worship is involved. Religion as a tag does not matter to dance. I am not talking about religion as a denominational tag, but as a divine experience. I am talking of religion in the higher sense. Taking off from there, let's now turn to synthesis and experimentation. To what extent is this seen in Kathak? P: Each and every dancer is trying to do something new. The expectations are also there - "What is next? What are you coming out with?" Every dancer is experimenting. As I said earlier, there is a vast body of nritta in Kathak. So, experimentation is always possible. Madhavi, you have been there and seen all in Odissi. Many people say they are tired of seeing the same stuff. Many dancers are coming out with new ideas and are criticized by the purists. What is your take on this? Are we going up, down, or forward in Odissi? M: Let's first be clear about what is experimentation. At every stage in Odissi, there has been experimentation. What about Guru Kelucharan? How did he bring about (the change) that he did? He created a new phase in Odissi. Of course, everything is rooted. Of course, parampara has to be preserved. It has a pravaaha, and what is created has to contribute to the ongoing stream. It is only then that the tradition lives. Experimentation has to emerge from the roots. If it is based on western dance and sought to be transplanted, I don't think it has any validity. It is the "conviction" of every individual dancer that is important. Nobody has the right to say something is wrong, even if it does not have any lasting validity. One may say, "This raag is wrong, this swar is not correct, this is out of taal, or this is not Odissi form," but what you are doing is entirely up to you. But if you are not totally rooted, it will be a mismatch. There was a ruckus about the costume used by Ramli Ibrahim for his girls when they performed here last year. What do you think of all the dust that was raised? M: First of all, stitched costume itself was new! Was it ever there in the temples? When originally performed, dance was not so technically challenging. It is quite different these days when we perform on stage, compared to when devadasis performed in the temples. Those days, it was less demanding. So, it is very difficult to say what the correct costume is. I personally feel that it entirely depends on the aesthetics of the person. Is Chinese silk that is worn by so many dancers today valid? Is it OK just because a lot of Oriya people wear it? Of course not. Orissa has beautiful textiles, and they should be used. So, it is not for anybody to say, "This is right. That is wrong." The essence and sanctity of the form should remain. Are you saying that, as in the case of the dance itself, there is a process of evolution in costume too? M: Yes. The same thing applies to jewellery. Devadasis shown in temple art wear such heavy jewellery that you can't dance with such things on. We really don't know how they danced. In those days, was there such heavy lighting as we have today? Did they sweat so much? For me, it is more important to have authentic Orissa weaving and proper traditional jewellery. Rama, is the dance world in the Bharatanatyam genre generally rigid in the matter of experimentation? R: No, no, no - not at all. There is a lot of new direction in Bharatanatyam in different parts of the country and the world - in Delhi, the US and north America, besides other places. But mostly, Bharatanatyam is centred around Delhi, Chennai and Bangalore. There is a lot of permutation and innovation going on. But what I feel is that whatever a dancer does, if it shows the dance form in good light, if you bring dignity to your dance form, you can never go wrong. Bharatanatyam throws challenges to me every day - every single day. At the end of the day, whatever I do should bring dignity to my dance form - whether I do a Thyagaraja krithi or French poetry! One last question for Madhavi. In Odissi today, the lyric has evolved. It tends more towards history and poetry, as in your presentation of Mayadhar Mansingh's work, than our epics. As a sincere and serious student of dance, what do you see about the future of Odissi lyric and interpretation through dance? M: I think we need to explore more of contemporary poets, and that's always welcome. There is so much good work happening in Oriya literature that would lend beautifully to interpretation. We should explore more of this. Of course, I am aware there is a lot of material in the classics that we have not touched. Then again, there is so much of Odissi happening in Orissa. So many young dancers are coming up, and they have a rich wealth of material to work with. They have a plenty to explore. Any particular poet or poetry for you to explore? M: Ramakant Rath and his poetry. Do you have his Sri Radha in mind? M: Yes, of course. (laughs)  H Balakrishnan topped his University in his subjects where, at graduation, he had Alternative English as a subject. Even during his teens and twenties, he used to contribute to leading magazines in India. In the recent past, he has been writing regularly for The Hindu Sunday Magazine and Literary Review - mostly on culture, the fine arts, artistes and literature. He has also done occasional research for the Reader's Digest. He has a collection of over 100 poems, some of which are available on the net. A book of poems is on the anvil. Balakrishnan, now co-Convenor of INTACH Bhubaneswar chapter, lives in the historic city of Bhubaneswar, capital of Orissa, India. |