|   |

|   |

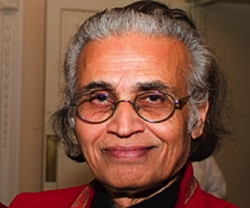

e-mail: sunilkothari1933@gmail.com Why Kumudini Lakhia's Kathak stands out for its presentation Photos: Sanchit Kapoor June 7, 2018 When Kumudini returned from London after performing with Ram Gopal and settled in Ahmedabad after her marriage with musician Rajani Lakhia, she was already an internationally renowned dancer. Her exposure to world dances, ballets, costumes, lighting and showmanship helped her a lot to improve the presentation aspects of Kathak. She received scholarship from Govt. of India to study Kathak under Lucknow Gharana maestro Shambhu Maharaj in Delhi in late 50s. She had studied Kathak under Radhelal Mishra of Jaipur gharana and dancer Ashique Hussain Khan. However, with her innate sense of aesthetics she was not happy with the way Kathak was presented in those years. She was aware that the art she was learning was from the traditional gurus who were supported by a feudal system. And that is the first thing she planned to do away with, to free Kathak from feudal system. During the Mughal rule Kathak in courts was presented to please the rulers and the salutations were de rigour, to the ruling Nawabs. Dispensing with it was quite tough, as the Gurus were not used to permitting such freedom to the disciples. There was such a slavish presentation in solo form. It is customary to recite mnemonic syllables, the bols, in a standing mike and perform nritta items like tode, tukde, tihai, aamad, parmelu. Often it is necessary if the accompanist table player is new one. He can listen to the bols and register it like a blotting paper and reproduce on tabla. But when a dancer warms up and executes vigorously she loses control over breathing and cuts a sorry figure. Kumudini arranged for someone else to recite the bols called padhanta. But what bothered Kumudini most were the way costumes were put on by the dancers. With a wealth of handloom and excellent fabrics she designed costumes which helped the Kathak form to shine. The skirts were so designed by her and her colleagues that the flowing of the skirt when chakkars were taken also circled in an artistic way. I remember once she was designing costumes for her new production in Ahmedabad in early seventies. She had invited me to see the rehearsals. The traditional silver like khadi print often seen in Rajasthan drew her attention and she used it on saris and also skirts, ghagharas. She explained to me why khadi print stands out for its subtle colour. With her exquisite colour sense, she was careful not to have clashing colours for costumes. She also was aware of terrible lighting with red, yellow, green, purple colour circular gadget that made a mish mash of colours destroying the beauty of the costumes. Over the years she set high standards in terms of costumes both for girls and boys. The long shervani like angarkhas with variation of subdued colours looked more dignified than the Lucknow type of coats, pyjamas and caps, which looked dated. She avoided shining material for costumes. Instead she improvised the costumes and removed caps. She removed waist bands. As a matter of fact Kadamb's history of evolving costume is quite fascinating. For her latest choreographic work Tarana composed and sung by Madhup Mudgal, she chose white costumes for both male and female dancers. The snow white costumes by young Anuvi Desai under supervision of Kumudini with exquisite lighting by Gyandev created an illusion of swans. The way the skirts were designed with two layers was done with a purpose. The two pieces of cloth flew like wings of swan, when dancers took chakkars. "The flying of skirts was carefully under control," said Kumudini.

Kumudini has been constantly aware of colours, weight of costumes, effect of lights on costumes and light design. Therefore it looks so professional and eye catching. "I do not like when dancers take chakkars, the hair and flowers come off and fly all over," Kumudini tells me in green room tightening the braids of young dancers. "I do not think that Kathak dancers have to be so careless. And walk to the mike and apologize. That is not professional." In terms of choreography Kumudini basing on the sound Kathak training she had received, still wanted to be different. "I did not want to imitate my gurus. I had always this urgency to be me. Whatever it was, architecture, agriculture, I wanted to create something new." Kumudini wanted to explore various possibilities in movements. In early seventies when she started choreographing with her disciples at Kadamb, she immediately stood apart from her contemporaries. "I looked at the clusters of dancers as a group, keeping one separate from the group and see how they balance themselves on the stage and space. Also find out the various levels, I can make them stand on a platform, and few to sit on the floor. Can I use different music within the tradition?" Kumudini mentions her early work of Dhabkar with original music by Atul Desai who having received training from Pandit Omkar Nath Thakur also was seeking such freedom. Their historic working together at Kadamb has given us excellent choreographic works like Venunaad, inspired from miniature painting, Drishtikon, using vertical hangings and dancers moving from one to another behind the hangings of different colours, Variations in a Thumri, Shakti and so on. Shakti was more of an abstraction emphasizing power in women. "An element of training needed to be shown but not too much of virtuosity," agreed both Kumudini and Atul. One of the memorable choreographic works has been Yugal featuring one male and one female dancer. Kumudini explored the possibilities of chakkars by keeping in centre the male dancer encircled by the female. Then female dancer stood in the centre and the male took rounds around her which created a different kind of energy and both the footwork and chakkars looked different than one solo dancer performing it. The music also was tuned differently enhancing the concept. With Atah Kim, meaning 'now what next,' Kumudini and Atul created history. The entire choreography using Kathak technique looked so unusual and different with only one frame which was supposed to be a barrier, like tradition which cannot be crossed. A group of dancers outside the frame and one dancer within the frame being opposed by the group if she stepped outside was conveyed imaginatively. Atul also used electronic music when opposition was suggested. A landmark production, it was part of the new directions in Indian dance. Five years ago Kumudini choreographed for Kathak Kendra Delhi, a new work titled Punarnava, using the Lakshanageet of Kathak by Bindadin Maharaj highlighting the salient features of Kathak like tode, tukde, agraferi, kavach palata and so on. Niratat Dhang was set to music by Madhup Mudgal using dhamar tala and also Tarana. The same old traditional composition took new avatar.

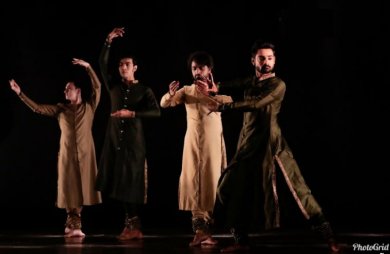

In the 10th edition of the Kendra Dance Festival curated by Shobha Deepak Singh, Kumudini Lakhia presented Movements and Stills featuring some of the excerpts asking Anuvi to design new costumes. Barring one male dancer Pankaj, the five other dancers were from Delhi, whereas all female dancers including lead dancer Sanjukta Sinha were from Kadamb's repertory. As Kumudini says in her choreographer's note: 'I am creating a structure of the fabric of Kathak technique designed to create patterns in space and time.' We see three dancers in dim light in graceful bent pose raising their arms over their faces to the note of melodious flute and slowly they appear clearly with other dancers and perform simple tode, tukde taking exquisite pirouettes dressed in whitish costumes with their skirts and covering layers holding their ends and waving a la Flamenco dancers. Keeping their heads high they execute movements which we all know as Kathak. But the way Kumudini presents them it looks refreshingly new. The youthful maidens cross the stage, move in circles, forming various patterns in two separate groups and challenging each other to dance the way they dance. The footwork is flawless and the patterns created enhancing their beauty. Among them the lead dancer Sanjukta Sinha dances taking leaps and landing on sam draws our attention for her incredible energy. Dhamar is described as an obeisance to the gods in heaven. It is written by Bindadin Maharaj in his ashtapadi of Lakshanageet composed in tala Dhamar to the music by Madhup Mudgal. Six young dancers dressed in long shervani like costumes enter from one end of the wing on stage in a walk becoming a warrior, and to the music displaying vira rasa, perform to the song Shankara bajave damaru and create a vision of various gods in heaven playing veena, and conch. For 'Shankha bajave Brahma, Narada veena' and so on, they dance vigorously in a tandav mode, executing footwork, breathtaking chakkars in fast tempo and the audience starts clapping spontaneously. The Dhamar tala becomes their challenging mood. Padhant, recitation of mnemonic syllables or bols, is an inevitable part of Kathak repertoire. To turn it into a special number looked quite innovative. Gyandev's imaginative lighting with two trellised windows on the back quite high and six dancers and six female dancers seated on the floor, gave a sense of the backdrop of a great height and as it were they were in a palace. They start reciting the bols 'thai tat a thai tat aa thai thai aa' and so on. The girls recite and the boys respond, like jugalbandhi creating repartee. Gradually rising in its ascending order the bols create hypnotic effect. Then one girl gets up and performs chakkar, the other two join her then the boys get up and in no time the entire group performs variations reciting 'agraferi kavach palata', the salient features of Kathak as penned by Bindadin Maharaj, taking movements in front with chakkars, and executing palatas throwing arms sideways body facing back drop, and dance in fast tempo. The spirit of challenge permeates the composition. And one enjoys it. One feels that this is entertainment. The joyous mood continues. The finale Tarana saw all dancers dressed in snow white costumes and bluish criss cross pools of light, moving on stage like creating illusion of white swans. Composed and sung by Madhup Mudgal the dancers flew across the stage. The jumps were light, pirouettes mesmerizing, lighting magical, the spirit of jugalbandhi catchy and the visual impact indescribable. Sanjukta Sinha danced as if the stage belonged to her; the female dancers moved crossing the rows of male dancers, turning all into a large circle, with foot work keeping the rhythm intact. They formed pairs, filled up the stage in arresting patterns, melting with each other, creating centripetal and centrifugal patterns in abundance, they brought down the house. Such virtuosity and flawless technique won them rounds of applause. It was infectious, the joy of watching Kathak in this way. It had a balletic look, and yet completely steeped in Indian ethos.

The surprise number was contemporary choreography by Santosh Nair. Using their excellent training in Kathak, Santosh explored how dancers could move differently, falling on floor, pairing with each other, with only one male dancer Pankaj and Sanjukta Sinha, entwining arms, hands and palms turning backwards, falling on floor and getting up. Their black costumes and loose black hair also danced with them. Choreographed to the music by Austrian musician Bernhard Schimplesberger with light design enhancing black in complete contrast to white costumes of Tarana, it extended for me the simile of white swan and black swan. The dancers used striking with palms different parts of body, tapped the floor with footwork, at times rolled on the floor and got up. Finally one by one, each dancer walked away to the wing in complete silence, suggesting silence as music. It was indeed interesting to see how they responded to different movements and still retained the basic Kathak. Santosh Nair managed to get best out of them. Kumudini's birthday was on 17th May. Introducing her dancers in the end she told with great sense of humour that next year she was turning 90 and would dance solo on the same stage. And she would start practice in right earnest and perform for us all. The audience lustily cheered her for this announcement and wished her a happy birthday. It is Kumudini's spirit that has kept her so active and creative. One thanks Shobha Deepak Singh for arranging such a wonderful show. We would like Kumudini to know that we all are waiting to see her dance next year.  Dr. Sunil Kothari is a dance historian, scholar, author and critic, Padma Shri awardee and fellow, Sangeet Natak Akademi. Dance Critics' Association, New York, has honoured him with Lifetime Achievement award. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |