|   |

|   |

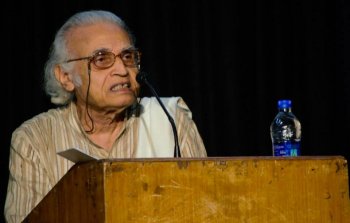

Constructive dance criticism - Dr. Sunil Kothari e-mail: sunilkothari1933@gmail.com September 13, 2014 (This paper was presented on Aug 27, 2014 at the ‘Dance Criticism - The macro and micro perspectives’ seminar hosted by Lalit Kala Kendra, Pune)  Photo: Madhuvanthi Sundararajan

Before I speak on the topic I have selected, ‘Constructive dance criticism’, I would like to say in brief what it was like to write dance reviews some 20 years ago when many dance critics’ opinions were taken note of. Then all of a sudden the English newspapers stopped reviews on all the performing and plastic arts, except on films. Only ‘The Hindu’ newspaper carried on Friday Review in most of the metropolitan centres where their edition is published. Edwin Danby, the American poet and dance critic, has observed in his book ‘Looking at the Dance’ in his seminal article on dance criticism that the dance reviews which appear in the newspapers are casually glanced through by lay readers mainly to see if their opinions tally with the reviewer’s. On the other hand, a dancer often reads the same review with x-ray eyes, reading into it more than it contains, so that often a review becomes a dialogue between the reviewer and the dancer. The scenario in the Indian context has to be seen keeping in view the nature of various dance forms, the aesthetic principles governing them, and the existing styles and schools. Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan in her magnum opus ‘Classical Dance in Literature and the Arts’ has observed: ‘The aesthetic enjoyment of classical Indian dance is considerably hampered today by the wide gap between dancer and the spectator. Even the accomplished dancer, in spite of his mastery of the classical technique, may sometimes only be partially initiated in the essential qualities of the dance form and its aesthetic significance. But in the case of the audience, only the exceptional spectator is acquainted with the language of symbols through which the artist achieves the transformation into the realm of art. The majority are somewhat baffled by a presentation which is obviously contextual and allusive but which derives from the tradition to which they have no access. Although they are aware that dance is an invitation, through its musical rhythms, to the world in time and through its sculpturesque poses, to world in space, in which the character portrayed is living, they are unable to identify themselves with him. Far less they are able to attain such identity with the dancer in his portrayal of the particular role.’ This being the state of affairs –which has partially changed on account of various strategies employed by dancers and with dance appreciation courses, lec-dems, etc., readers of reviews who have not seen the performance at best get only an impression of the event. Reviewing dance on the other hand makes several demands on the critic. He is expected to be well versed in the technique of dance and music, the aesthetic theories governing dance, as well as the poetry, the theme and the content of a particular performance. This is a tall order, but only one who has some knowledge of these matters is really qualified to review dance. Since the thematic content of our classical dance derives from the epics-the Mahabharata and the Ramayana- and other mythological lore, knowledge of this genre of literature is a must. So far as the senior generation of critics is concerned, their acquaintance with the literature is fairly sound. There are several versions of mythological stories in different parts of India and the interpretations by dancers are likely to differ. In this situation familiarity with mythological literature helps a great deal. It is obvious that knowledge of Sanskrit is necessary for the dance critic in India. The manuals dealing with the technique of Indian classical dance are in Sanskrit and so are the commentaries on these manuals and rhetorical works. The Natya Shastra - dealing with dance, drama, music, architecture, poetry, and other related matters - is among the important texts in the field. The study of these texts helps one acquire a sound knowledge of the principles of Indian dance as well as its technique. However, one cannot understand dance technique only by reading these manuals. What helps a dance critic most is practical knowledge of dance: this technical knowledge gives his writings a sharper focus and insight. There is another difficulty ahead for the critic. Although, in the Indian context, a critic is expected to review different dance forms - Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Manipuri, Kathakali, Odissi, Kuchipudi, Mohiniattam and recently recognized eighth classical dance form Sattriya of Assam, it is almost impossible for him to know all the languages of the songs in these dance forms to which the abhinaya is enacted. However, there is at times almost a one to one correspondence between the word sung and danced through angikabhinaya, including the mukhajabhinaya and the hastas used to tell a story, so it is possible for a critic to understand the import of the songs. While a dancer can learn dance at various dance institutions, a dance critic in India has to be an autodidact. The only way he can learn his trade is to watch dance continuously. There are no facilities or evolved methodologies of learning dance criticism. Even at the few universities in India where dance departments exist, I do not know of any course for dance criticism introduced so far. It would help if such courses were introduced in the dance curricula. The discipline of dance criticism could then develop in this country and could play an important role in the development of dance. The existing body of dance criticism in India is still meagre. This subject of dance criticism has received attention only in the past four decades. No systematic study of the history of dance criticism in India has been undertaken so far. Nartanam quarterly is to bring out a special issue devoted to dance criticism. In the early ‘50s the role played by Dr. Charles Fabri in Delhi to enthuse people to watch dance was very significant. With the formation of Sangeet Natak Akademi in Delhi and its counterparts in the States in the ‘50s as well as other government and private agencies promoting dance, public interest in dance and reporting of dance events in the press received fillip that lasted till 1995. The Times of India group of newspaper took a decision to stop covering reviews of all performing arts, plastic arts, literature and systematically killed the institution of criticism in general and dance in particular. Unfortunately, the trend set by The Times of India was followed by all major English newspapers, including The Economic Times, The Financial Express and The Business Standard, which used to carry special columns by dance critics in their Sunday editions. In such a situation, whatever space in print media or in electronic media, website, blogs, e-portals like www.narthaki.com, Kutcheri Buzz and other similar journals is available has become very important. However, the dominance of print media cannot be minimized. Most of the dancers still are not savvy to use electronic media. The newspaper barons found out that this removal of dance criticism has not affected their circulation. They found it lucrative to use that space for advertisements. In 1995, some twenty years ago, the dancers wearing designer black clothes held a meeting in Delhi to protest against the newspapers’ decision and submitted a petition to the news barons. They did not take along with them the painters, musicians, the theatre people, and the writers with the effect their voice in isolation was not heard. The media exploited the situation and carried photos of dancers in black clothes, almost ridiculing them. The dancers have been crying hoarse and in wilderness citing existence of sports page and not providing arts page. Such being the case, the issue of ‘constructive criticism’ becomes most important. Criticism unfortunately in Indian context is not understood by the dancers. I suspect and have come to believe that since the theme of dance centres round the gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, they are all the time being praised. Therefore if something is offered as ‘critical evaluation’ of dance performance in place of mere praise, the dancers are not used to taking it gracefully. They are hurt if there is the slightest criticism. This feeling of ‘hurt’ is further aggravated if criticism is done in ‘harsher words’ which stings the dancers and it ‘rankles’ for a long time. The dancer’s and the critic’s relation gets estranged. The critic then is seen as a person whom dancers do not want to attend and review their performances. A few examples would suffice. In the mid seventies, I had criticized few performances of dancers strictly within the parameters of aesthetic principles of Rasa Theory. They did not go down well with the dancers. In those years in ‘Readers Write’ columns, dancers used to reply and sometimes as the editors liked the controversies, attention was drawn to dance reviews. But the end result was not happy, as readers in general could not follow what the issue was. Soon the critics realized that if the readers are not well informed the sympathy goes to the dancer, as she makes a hue and cry about her dedication, life time devotion, sacrifices made by her etc. Fortunately, if the editor is well informed about the arts, he stands by the critic. Dancers as some of us know have sent legal notices to dance critics. But it has not helped either the dance critic or the dancer. When this battle between dance critics and the dancers assumed ugly proportions, the editors got fed up with the entire situation. And it was also one of the reasons why dance reviews were taken off from the newspapers. Many dancers had access to editors, press barons, ministers through whom they brought pressures on editors / press barons to remove the critics. During my tenure at The Times of India, I was guided by senior scholars like Dr. Mulk Raj Anand and editor Shamlal, an erudite person. They guided me about how to write what they termed as ‘constructive criticism’, to couch the criticism in gentle words. The phrase they asked me to use more often was ‘how marvellous it would have been if the dancer had presented her interpretation in such and such manner.’ They also advised me never to write on the physical disadvantages and comment upon it, in particular of female dancers. It has become folkloric now in knowledgeable circles that we used to write about dancers who ‘were pleasantly plump!’ but never stated the obvious. Or used the French term ‘avoirdupois’ suggestively to convey the image of a dancer. I remember Dr. V. Raghavan telling me the Sanskrit saying: ‘Kantasammitatayopadeshah’ - meaning to say to beloved gently what has to be said indicating at shortcomings without making it a reason for contention! That requires a lot of patience and discipline. And lot of sense of humour. We know that the last is in severe short supply. Fortunately, today the type of criticism which late critic Subbudu used to write is no more in vogue. His was an exceptional case. He was very witty and his remarks, often ‘one- liners’ were remembered by readers for its wit and personal remarks. That his knowledge of music and dance was sound, none challenged. However he had over the years developed a style which entertained the readers at the cost of the dancers and musicians. The artists felt humiliated. And there are several anecdotes, many humorous ones which older generation remembers. But now it is part of the history. And perhaps it is good that that sort of criticism is now out of date. Critics find it difficult to express their opinions in print about performances which are not up to the mark. However gently it is stated, the dancers do not like it. In India, unlike in the West, dance critics and dancers mix with each other, visit their homes, accept their hospitality, become friends, meet socially and in general develop bonhomie. The distance necessary between dancers and critics is not maintained. Even if it is maintained, by and large the criticism is not appreciated, whereas in the West, a critic does not develop friendship with dancers and strictly keeps away from them. It is considered ‘a conflict of interest’. In India only in case of The Hindu newspaper, one finds that a critic is not permitted to write reviews of a critic’s daughter or daughter-in-law. But otherwise the bonhomie between dancers and critics remains. Therefore even when one wishes for the ‘constructive criticism,’ it does not exist. Many dancers misunderstand the criticism as an attack on them even when couched in polite language. What could be ‘a constructive criticism?’ When a dancer deviates from the norm, the aesthetic principles and seems to violate the spirit of the dance tradition, a critic is bound to draw attention to it. And disagree with the dancer. The disagreement is often misunderstood. The limited space within which a critic has to write about the performance also causes problems. It is important for a critic to draw attention to flaws in a dance performance. If the technique is below par and abhinaya is found lacking in depth, or appears superficial, a critic is bound to mention it. Ultimately, the excellence is the final hallmark of Indian classical dances. There are no short cuts to success in classical arts. We all know that there are only two types of dancing: good and bad. But bad dancing is not specifically told by a critic as bad dancing in writing. He suggests it as politely as he can. The saying that criticism is like walking on an edge of a sword, ‘Kshurasya dhara’ is true. Critics in general are not liked by the dancers, unless their writing is approved by the dancers. Critics know that it is a thankless task. When a critic earns reputation as generally being fair in his assessment, he earns credibility. That credibility is also at risk as the moment a critic offers criticism, the dancer dismisses him as one who is ‘ignorant’ or ‘has a hidden agenda.’ Arnold Haskell, a renowned British critic from London in his biography ‘In his true centre’ has mentioned that a critic in his reviews must never ‘settle scores’ with dancers. Not only it is unethical but hurts dancers and is never forgotten. The written word has tyranny and power and it can harm a dancer’s career if a critic for personal reasons settles scores. Similarly, a dancer has to be extremely careful about passing comments about a critic’s ability to evaluate the performance. The world of dance is small and such remarks do not go unnoticed. They result only in unpleasant relations between dancers and critics. If I have dwelt upon the negative aspect of criticism, I have done so out of my experience over the years. I have come to believe that dance criticism has bleak prospect in present times. There is no possibility of reversal to former days when many newspapers had different critics. The confusion is further confounded by lack of space in print media. A critic from print media also knows his power and the vulnerability. In absence of critical opinions of other critics, the only one critic’s reviews in those regions, where the English press provides space for reviews to a specific person to review, gains a lot of power and other voices are not heard as was the case earlier. The public also gets used to critical opinion of that critic’s evaluation only in that city/region, leaving little scope for different views. It was possible earlier to have different opinions. Today it is not such a case. If only one English newspaper offers limited space for review to one person only in different cities/regions, such ‘a virtual monopoly’ is bound to give rise to ‘one sided view’ however objective the critic may be. The dwindling number of critics in dance is the main reason for ‘the shrinking space’ in print media. If, few of us, senior critics, who write both in print and electronic media, internet, have survived, we have survived because of some credibility and reputation as scholars and track record over the years. One can forecast that if this situation persists, with shrinking space in print media, whatever little ‘in terms of criticism’ is seen today will also vanish. Frankly speaking the press barons are heartless. They have no respect or consideration for arts. To them whatever little space is available in print media they would convert it into lucre and consider how much money they may get for hiring that space instead of having criticism. Be that as it may. For future critics there is little critical writing on dance that a critic can fall back upon. The available books on dance are of diverse nature, ranging from scholarly works to popular writings. There are few research journals publishing papers on dance. There are only three to four periodicals devoted exclusively to dance - Sruti monthly (it covers classical Indian music, dance and of late theatre also), Nartanam quarterly, Angarag half-yearly and Attendance, annual. No organization for dance criticism has yet been formed in India, as in West, but in absence of space for dance criticism it does not help to form one. Publication of collection of critical writings is essential for the scholarly study of dance. Another important requirement is archival material and access to it. The Dance Collection of Lincoln Centre remains a dream for all in India. The Mohan Khokar Dance Collection could be one such institution. When we look at the dance scene in India, we cannot but help reflecting upon it. It seems to be saturated with mindlessness, populated with synthetic dolls and tinsel goddesses and very few flesh and blood human beings, who look at life and society around them. While offering a critique of dance scene in India, one will have to take this seriously into account. The critics and dancers have to grow together. And not in isolation or in a manner that critics will continue to have a patronising attitude and dancer’s contempt for critics. There are no short cuts to becoming a dance critic. A critic has to constantly grow and sharpen his tools and broaden the scope of dance criticism, as bigger challenges face dance critics today than their predecessors two decades ago. Dance criticism cannot remain limited to reviewing pure and simple; it must act as a vehicle of change and mould public taste accordingly. Bibliography New Direction in Indian Dance: Collected writings from the seventh Dance in Canada Conference held at University of Waterloo, Canada, June 1979. Performan Press, Toronto, Canada, edited by Diana T. Taplin: See in particular: On Critics and Criticism of Dance. Writings on Dance (1938-68) by A.V. Cotton, edited by Katherine Sorely Walker, Dance Books, and London 1975. See in particular: Critics Function. Looking at Dance by Edwin Danby, Curtis Books, New York, 1968 In His True Centre: Autobiography of Arnold Haskell. Adam and Charles Black, London, 1951. Dancers under my lens: By Cyril Beaumont. Cyril Beaumont Publications, London, 1950 The Philosophy of Dance: By Paul Valery. Collected works of Paul Valery, vol 13, Pantheon Books, New York, 1964. Watching the Dance: By Marcia Siegel, Houghtoin Miffin, Boston, 1977 The Functions of a Critic: By Clive Banes in Visions edited by Michael Crabb, 1978, London Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts: By Kapila Vatsyayan, Sangeet Natak Akademi, and New Delhi 1968.  Dr. Sunil Kothari is a former dance critic of The Times of India group of publications, former Dean and Professor, Dance Department, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, and School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Post your comments Pl provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |