|   |

|   |

Master of Arts: A Life in Dance - Bhavanvitha Venkat e-mail: bhavanvitha@gmail.com November 4, 2013  The world of

Bharatanatyam has been a preserve of women. There is a

welcome change in the scenario as we start seeing the

emergence of the male dancer. It is a known fact that the

stage for classical dancers is itself limited and not much

material is available in the public domain to understand

classical dancers. The world of

Bharatanatyam has been a preserve of women. There is a

welcome change in the scenario as we start seeing the

emergence of the male dancer. It is a known fact that the

stage for classical dancers is itself limited and not much

material is available in the public domain to understand

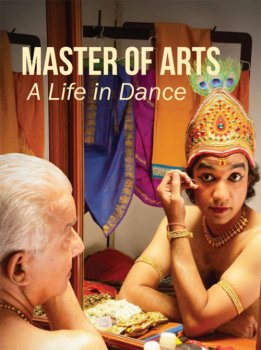

classical dancers. Just when classical dance enthusiasts are looking forward to learn more about male dancers, Tulsi Badrinath writes about them in her aptly titled ‘Master of Arts: A Life in Dance’ (Hachette India publication). The attractive cover has Guru VP Dhananjayan looking into the mirror at his own younger picture (in the form of his son CP Satyajit). It comes as no surprise that the work should be coming from a classical dancer as others may find the context, content and the very background unfamiliar. Who else would understand the “perilous journey” of a male dancer, and his “worries over decisions” and, notions like “the male dancer in the traditional margam is like an illegal immigrant.” Tulsi’s choice for illustrating the life of a male dancer is of course her guru VP Dhananjayan. The maximum content of the book is dedicated to the life of her guru interspersed with the narration of her own life in dance. After a brief prologue and introduction, we step right into the life of fourteen year old Dhananjayan. Thereafter the journey smoothly proceeds to the distinct happenings in his life as he reaches his dance universe - Kalakshetra. Tulsi engages the reader actively thereon with story of her guru and her own dance as these are brought in alternative chapters. The lasya-tandava flavor adds to the appeal as the young Tulsi unravels details of her observations about the boys in her class. Dhananjayan turns into a young man and dance becomes an integral part of his life. We are introduced to the various aspects of classical dances one by one as the narrative gains momentum. In a rather subtle manner the concept of guru-shishya parampara is explained. For those not familiar with classical dance, the author’s approach is surely useful and the interest generated in the beginning is sustained. To those that are familiar with Dhananjayan, the rather sensitive nature of the events that happened in his life get presented with adequate care and for that the author needs to be commended. Soon, we get past the incidents that lead to Dhananjayan’s founding of his own school. It goes without saying that his reverence and relation with his mentor Rukmini Devi Arundale is maintained in dignity. Through this journey, the writer deftly looks into the many aspects of classical dance including the classroom discipline, supporting artist cooperation, close friends, economics etc. I leave it to the prospective readers to personally read and gain from the wisdom gained through the experiences that are illustrated - insights of the profound impressions and impact people made, like Kodi Amma, Asan Chandu Panikker, Athai, Shantha, Krishnan Nair… and others. Tulsi expands her study of male dancers by including some chapters about other male Bharatanatyam dancers. She chooses to cover wide backgrounds from where they emerge into dance, and even wider outlook that they express in their own words. The author could have edited out personal details like the names and opinions of one or two dancers as these are unverifiable and may be subject to personal bias. All in all, the male dancer is for sure at the crossroads. The author’s style of writing is easy for reading and evocative too as the times and real life events are replayed in front of our eyes. The emotive content is preserved throughout the book. The “good” and “bad” of times are given due importance, respect, and there is no judgment and interpretation enforced. You come across illustrious personalities, even feel the interaction with them with the same comfort as in a chance meeting. Some of the chapters are found to be losing the order that we get used to in the start. The message and conclusions need to be brought clearly. It would have been nice to see a couple of color pictures too. Here are some examples of the artistry in language and selection of incidents: Find Navtej speaking to you, “It was June. There was no outer boundary to Kalakshetra in those days. I loved the place; it was like an enchanted wood. I just spent the entire afternoon there, lying on the sand….” and confessing elsewhere to his personal feeling. “The female dancers were too bedecked…..I did not find it beautiful.” Or, the recollection of a gleeful feeling from Narendra Kumar at, “I started earning a little.” The first thing he did was to spend 350 rupees on a bus pass. “I could travel anywhere in Chennai, twenty four hours.” Or a revelation, “Who will watch a man dancing…” Or the intrigue in her words when she says, “He had the faraway look in his eyes again.” There are many more of these liners. The author has come out with a good book about classical dance and has substantially covered the scope of her study. There are many things to learn and know in this book. So my recommendation - buy the book and read it. Bhavanvitha Venkat is a writer, critic and Kuchipudi dancer. He is a finance consultant, advisor to cultural institutes and likes to work on creative ideas.  Post your comment Unless you wish to remain anonymous, please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |