|   |

|   |

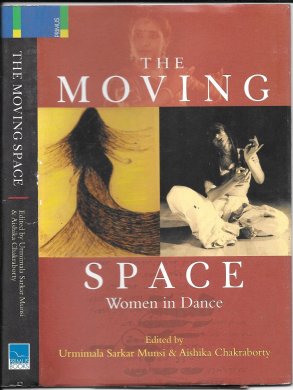

Indian Dance under Gender Radar Indian Dance under Gender Radar - Dr. Utpal K Banerjee e-mail: ukb7@rediffmail.com June 4, 2018 The Moving Space: Women in Dance Ed. By Urmimala Sarkar Munsi & Aishika Chakraborty Primus Books, Delhi, 2018 ISBN: 978-93-86552-50-1, Rs. 1395 As the book introduces itself, it highlights the idea of the 'space' created, occupied and negotiated by women in Indian dance. It initiates a dialogue between dance scholarship and women's studies, and brings together scholars from a multidisciplinary background, emphasizing the cardinal point that research and practice have roots in both these areas. The book takes dance as a critical starting point, and endeavours to create an inclusive discourse around the female dancer and the historic, gendered and contested 'spaces' that accommodate, or are created by her. This is quite an agenda, but the book surprisingly is able to do ample justice to its given mandate. The book appropriately sets out to understand the complex relationships among individual experiences, gendered representation and cultural constructions in the realm of dance in India. Scholars of dance history and women's studies have contributed the historical trajectories of dancers' journeys - drawing upon individual histories of women dancers: temple dancers, nautch girls and classical dancers. It often straddles sociology, dance history and women's studies simultaneously and venture beyond, to look at the multi-faceted life stories of embodiment, empowerment, exploitation, subjugation and subversion - repeated across social space and time. For instance, in "Introduction", the Editors explain how tribal women dancers - celebrating the birth of a child or welcoming a bride to her home - occupy space in a private domain, culled from the community life. In contrast, dancers from the classical forms of high art occupy a space which is public and framed within the aesthetic understanding of their norms of presentations. The popular Bollywood form - often becoming the country's identity through a huge screen presence - refers to an altogether different space, structured and controlled by market-led salability. Another dimension is revealed by Uma Chakravarti (in "The Devadasi as an Archaic Historical Artefact") in tracing social changes in the early 20th century. Having taken the reformist position that the tradition of dance as practiced by the devadasis (temple dancers) had become degenerate, E. Krishna Iyer's mission was simply cut out for him: 'Let temple dancing end, but let the art form - christened Bharatanatyam - be saved'. Affirming this position, he publicly performed the dance dressed as a woman to reveal its highly evolved aesthetics. Rukmini Devi Arundale completed Iyer's mission by patronizing some of the nattuvanars who began to teach Bharatanatyam at Kalakshetra. The career of M.S. Subbulakshmi, the most famous devadasi of her times, is a striking contrast to that of Balasaraswati, her life-long friend and a stalwart among the devadasis. While 'Bala' went on to perform Bharatanatyam with her strong emphasis on sringara abhinaya in padams and javalis that singers in Bala's family kept alive - refusing to be cowed down by Rukmini Devi's sanitized re-invention of Bharatanatyam -- 'M.S.' re-invented herself as the most famous singer of Meera's bhajans, effectively erasing her tainted birth stigma in a devadasi family. As brought out by Ratnabali Chatterjee (in "The Nayika and the Nautch Girl"), from the beginning of their rule in India, the discomfort of British officials was quite apparent with the people whose existence wandered beyond the British concepts of civil society. Among others, women dancers - generally known as 'nautch girls' -- were herded together on official records as 'prostitutes', denying the indigenous categories like 'devadasis'(temple dancers) and 'baijis' (courtesans) their proven histories as performers and artists. This ran counter to India's hoary texts like Vatsyayana's Kamashaastra - belonging to 2nd to1st century BC -- that mentions Nati as an actress. Bharata's Natyashastra - from around the 2nd-3rd century AD - categorized them as Nayikas where the courtesan's salon provided the actual setting in a world of 'amours'. Kautilya's Arthashastra - considered complimentary to Vatsyayana and written around the same time - categorized courtesans as artists in a hierarchy of social order where dancers, actresses and musicians were all listed according to their merits and paid taxes to the state. Both in Buddhist and Jain texts, 'ganikas' (courtesans) served as central icons through whom an entire historical era is formulated. As narrated by Pallabi Chakravorty (in "The Tawaif and the Item Girl"), in the Indo-Islamic tradition of music, dance and painting, the tawaif (courtesan) was central to an aesthetic Indian identity that not only traced back to the splendours of the Mughal court, but also to the reign of Wajid Ali Shah whose courtly traditions of music, drama and dance gave birth to many modern performing arts sensibilities, ranging from Parsi theatre to the present day Kathak dance. Interestingly, the founding members of both the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League - products of English Victorian education - rejected the tawaif on the grounds of sexual promiscuity. Evidently, the Indian women had to be refashioned, re-educated and reinvented in the spiritual image of the Hindu divinity: Durga, Sita, Saraswati and Radha. On the contrary, there is the considered view of the aesthete Devdutt Pattanaik, "Every time I watch a Bollywood item number as well as 'empowered' women displaying their sexuality and objectifying themselves, I see beyond them the faces of hundreds of smiling devadasis and nautch girls well versed in song and dance, who were mocked and rejected by the puritanical society as 'prostitutes'." Two contemporary cases stand out in this medley of identity and creativity, which have been dealt with at length in this study with a gender lens. As seen by Urmimala Sarkar Munsi (in "Performance Sites / Sights; Framing the Women Dancers"), the first is that of the contemporary Indian dancer-choreographer Manjusri Chaki-Sircar (1934-2000), whose Navanritya has been analyzed, following the clues offered in her autobiography Nityarase Chittamama (literally, 'My heart drenched in dance' - Miranda, Kolkata, 2000). Her own story is seen as a signature of herself in the moving space of modern dance and as a testimony of a new woman's life who dared to dance out her resistance against the hegemonic mainstream cultural diction. Manjusri's idiom evolved from the culture-scape of Bengal, before her travels to Africa and the USA, with artistic encounters that further changed her dance lines. Exposed to a variety of physical traditions - from classical to folk; from the Bolshoi Ballet to Martha Graham's Cave of the Heart; from the 'Third Theatre' Movement to the parallel cinema - Manjusri embodied what we call 'glocal', written all over her auto-(choreo)-graphs. Her dance arguably signaled a paradigm, deviating sharply from the colonial modern, from the prevalent 'Rabindra Nritya' and the neo-classical rejuvenations. As brought out by Sadanand Menon (in "Chandralekha: Breaking Free to Counter the Nationalist Narrative in Dance"), the second case of the Bharatanatyam dancer Chandralekha (1928-2006) stood out as among the most important artistic voices from India in the space of past several decades. Chandralekha's critical aesthetic questioned the reduction of the body to merely something pretty or ornamental or instrumental. She celebrated the intense play between the subtle and the manifest body and its expressions, through purity of line, and the extension and dilation of the energy field. Her central premise remained the need to recover the unity of the body in fragmented times and, within that premise, retain the indivisibility of the entire span of sexuality, sensuality and spirituality. The core concern for Chandralekha in all her works - from initial Prana to the final Sharira - has been the women's question and, related to it, the questions of erotica, of femininity in women - as well as in men - as also what is it that generates bhava (emotion, mood) and rasa (essential and aesthetic understanding) in the body. Across her oeuvre, there are the recurring flashes of unusual, uncommon, unconventional depiction of women, not familiar to the imagery within classical dance narratives and their stereotyped mythological references. Those familiar with Chandralekha's works remember having been amazed -- and thrilled - with representations of women as Naravahana (woman riding over man) in Angika; Sakambhari (woman giving birth to nature and all creation) in Sri; Salabhanjika (woman as fertility and prosperity) in Mahakal; or Bhayankari (woman as terrifying, beautiful and autonomous) in Sharira. In the broader conclusion from the book's analysis, as provided by the Editors (in "Moving with a Purpose"), one may look at Feminism, defined thus by Black feminists: A movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression. Clearly, Feminism is not anti-men, but against discrimination and patriarchy. Like most other ideologies, Feminism is a discourse, an ideology, a way of looking at the world, as a program of action and activism. Feminism thus walks on two legs of theory and action. The actions are to challenge patriarchy and unequal power relations within families and societies, while the activist theory is the raising of the voice - as in this book - to implement actions through Indian dance that hopefully lead to an end of the prevailing inequity.  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. Post your comment Unless you wish to remain anonymous, please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted in the blog will also be featured in the site. |