|   |

|   |

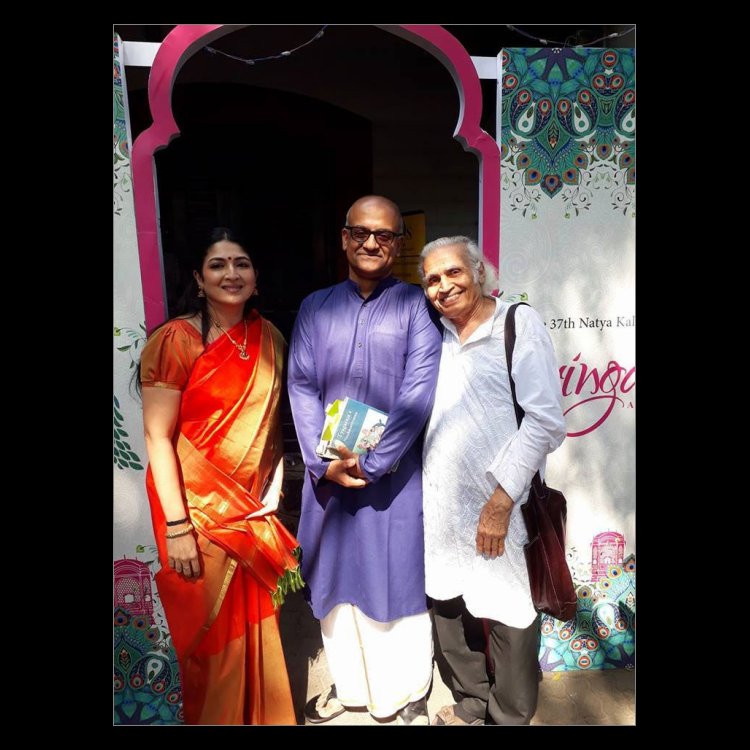

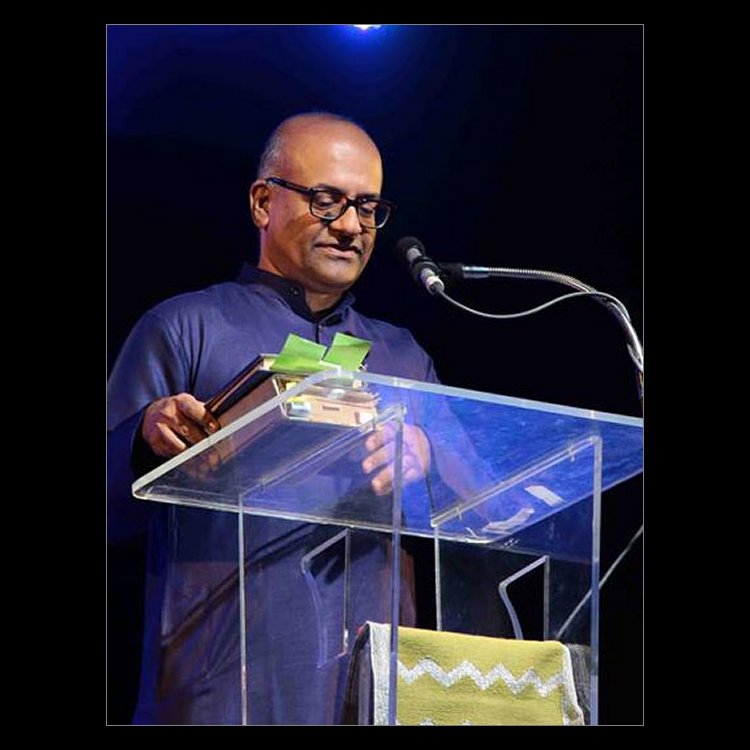

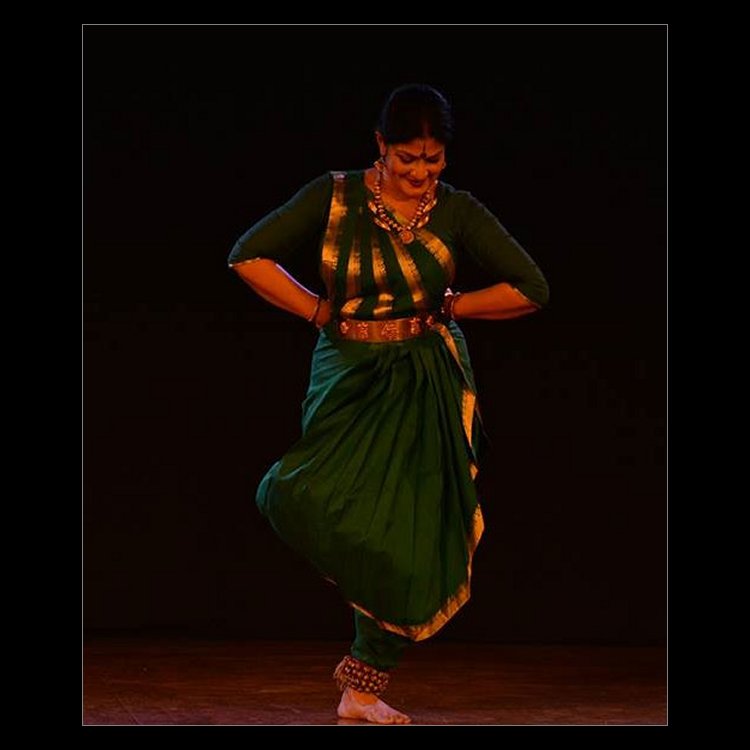

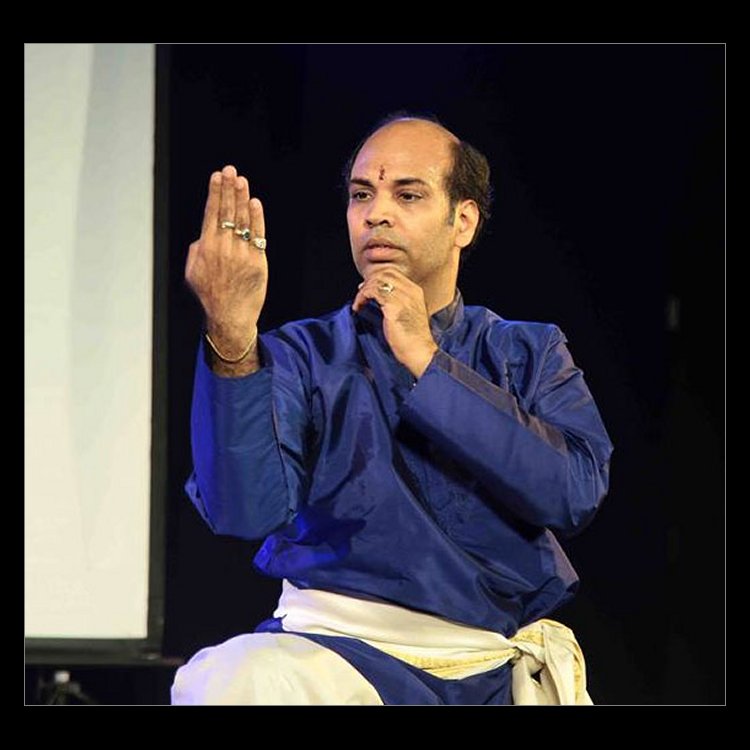

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com Sringaram: 'Leitmotif' for Bharatanatyam's dual anguish/ecstasy landscaping Photos courtesy: NKC January 19, 2018 Given the uniformly large turnout for each of the five days of the 37th Natya Kala Conference mounted by Yagnaraman Centre for Performing Arts and Sri Krishna Gana Sabha, convenor and designer Dr. Srinidhi Chidambaram, would seem to have once again proved her mettle for immaculate planning and organisation. And as a rare case, realising that hers is not an easy act to emulate, the committee of the Sabha announced unanimously selecting her as the Convenor for next year's Conference too. Her theme of Sringaram -an immersion, with participants pertaining to different age groups and mindsets representing different dance traditions along with scholars and poets, brought together a wondrously varying landscape etched with myriad images on the subject of sringaram. Ironically dubbed the 'King of Rasas' despite its wide range of expressions spiritual/sexual and erotic/ physical/ metaphysical, largely articulated by female performers, Sringaram's greatest quality is that it is never monochromatic. Not excluding the inauguration with the Natya Kala Visharada ha conferred on dance writer and publisher of the annual journal Attendance Ashish Mohan Khokar, no session was allowed over indulgent rambling - and here Srinidhi's unobtrusively firm reminder of abiding by the clock to every participant, played the main role. Devdutt Pattanaik, an unlikely combination of author, mythologist and leadership consultant, started the proceedings with his peppy talk on 'Love in the Kingdom of God.' Sringar as sublime eroticism represents abhang or that which takes away division or bhang. But the bhang of polarities pulling in opposite directions before uniting and becoming one, make up the subject matter of dance- for once the division is resolved and two opposites merge into one, there is no conflict. There is no swahiya without the parakiya and each side needs the other to see itself, drawing its identity from the other. Man as prey cannot exist without the predator, ever on prowl. Even in the Kingdom of Heaven ruled by Indra with apsaras dancing and Somaras flowing, the consuming flame of desire brings in insecurity - with Devas and Daityas in an eternal tug-of-war, churning the oceans for the immortal ambrosia. The nayika in sringar wants her anga to be consumed by the fires of desire. She offers herself as the bhog for the bhogee. Right from the RigVeda with Pururava crying for Urvashi, sringaram has been the recurring theme. Sringaram in different traditions The burden of Geeta Chandran's lec-dem, recalling what she had been taught under Swarna Saraswati, was on the need of the hour of revisiting the greats to capture the glory of this continuum of Sringara-lahiri, rather than engaging in amateurish attempts to create something new. Rendering part of a Sabdam before proceeding to full fledged abhinaya of excerpts from "Mohamana en meedu" or the Shahana Padam "Mogadochi Pilichedu" she spoke of the wonder (adbhuta) of exploring the same line without recourse to the narrative method of story telling. Perceiving beauty in the entire bodily aptitude with economy of gestures, accompanied by nuanced singing, and preserving the varnam structure in its entirety, was what the old school traditional approach was all about. She affirmed the need for 'Going through the grind' (without the present approach of learning only what can be saleable or performed) before venturing into newer terrain. Her own creation in trying to engage present day audiences was based on Vraj poetry, a composition from Harivamsha "Khelat ras rasika bhaja mandal" in raga Kedar rounded the lec/dem, her entire demonstration accompanied by the refined musical support of singer Venkateswaran, along with violinist Raghavendran, and nattuvangam lead provided by Vasudeva Iyengar. Slide show

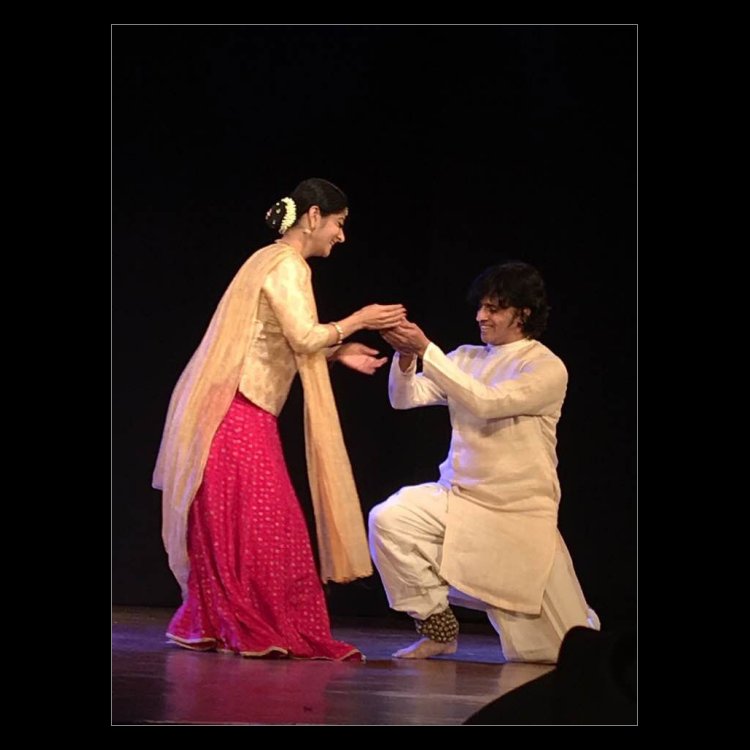

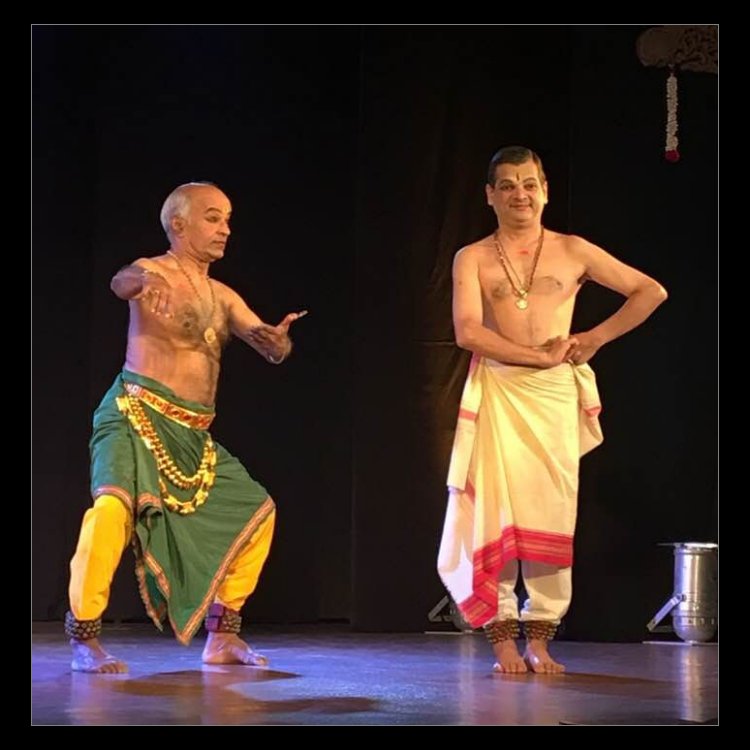

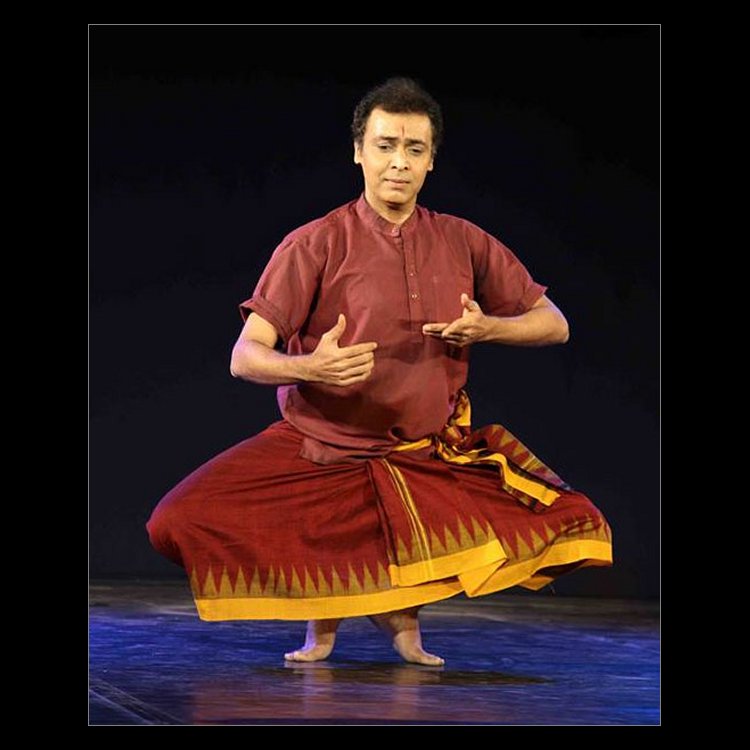

Guru Sadanam Balakrishnan demonstrated how sringaram in a Kathakali play may have little connection with the episode the entire play deals with as in Nalacharitam where Nala's sringaram concerns all aspects of this mood as dealt with in Kathakali. Generally set to Adi Chempada talam, 4 kale in a very slow tempo, the performance demands great prowess in the actor in being able to hold each moment for so long. Kathakali has rajasa sringar unlike satvik sringar in other natya traditions. High stylisation enables the advantage of even the most flagrantly explicit scenes posing no problems of overstepping limits of propriety. In Bali Vijayam, Ravana's keshadipada description of Mandodari is a case in point. Carefully observing the loved one or Noki kaanal (in raga Paadi which is special to Kathakali music), the demonstration with Sadanam Srinatha as Mandodari in streevesham was followed by a unique scene in Kambodhi of Mandodari being slightly confused by her love for Ravana whose dashamukha or ten heads, each in a different mood, are fighting one another on which one is to be blessed (karavimshati dashamukham) by Mandodari's kiss. Sadanam Sivadasan as vocalist was accompanied by Jitan and Sadanam Devadasan on chenda and maddalam respectively. Very eloquent with quotes from Anandavardhana, enriched by cross references from the other texts, Kathak dancer Nirupama (who was partnered by husband Rajendra) dilated on 'Hues of Sringara in Kathak.' Speaking of the origins of Kathak from Ras in its madhura bhakti form, she further stressed the Krishna focus in the dance with the example of Wajid Ali Shah's Rahas, wherein even the seedi hath ki gat symbolises Krishna's mukut with the top hand, with the extended right hand showing holding Radha. Given all the examples of sambhoga sringar based on the 13th canto of Raghuvamsha where even Nature shares the sringar mood, and explaining details of Udeepana Vibhava and varnalankara in the select passages, one only wished that the actual rendition through movement had been as convincing. First was the mistake of not having music and making a dumb show of stances to show how Kathak's Anga bhava without words can in Gat nikas and Gat bhav suggest sringaram through stance and movement. The Raghuvamsha verses of Rama/Sita coming together after all the travails, and leaving for Ayodhya in the pushpavimana, 'mukharpaneshu prakrtapragalbhaha' with Rama pointing out landmark locales, neither in the movements with leg stretches not characteristic of Kathak visualising the air borne pushpavimana nor in the short characterisation of Rama and Sita (Rajendra was Rama), did the presentation live up to the fine reputation this couple have earned for their Kathak. Showing how Guru Vempati Chinna Satyam changed the exaggerated gestures for expressing sringaram characterising the male dominated Kuchipudi of old, Jaikishore Mosalikanti began his lec-dem with the beauty and subtlety injected in the guru's concept of Rukmini in the pravesha daruvu wherein the state of mind of the heroine tailored even the teermanams injecting a certain quality to the angika, the music by P. Sangeetha Rao in raga Poorna Chandrika adding to the mood through word and melody. Mosalikanti kept to simple movements without undue ornamentation as characterised by the guru's approach in a composition like "Paluku thenala thalli" in Abheri, the tunefulness and clarity of diction in the tape with Radha Badri's singing, providing one of the best examples of how to sing for dance. The Mohiniattam version of sringaram 'Alarsaraparitapam' as demonstrated by Nina Prasad pertained to Swati Tirunal compositions. Describing his compositions as by "an incredible vagayekarar" with the creator becoming the nayika himself transcending all gender distinctions, Nina Prasad stated that his compositions in the raga bhavam and swaraksharas, apart from the sahityam provided the performer with a 'spiritual sub-text' to elaborate on. With vocalist Madhavan Namboodiri, Ramesh Babu on mridangam, Eshwar Ramakrishnan on violin, Arun Das on edakka and nattuvangam by Ruku Prasad, Nina rendered what amounted to a formal performance, taking compositions like the varnam "Sumasayaka" in Shuddha Kapi, followed by a Padam "Aliveni endu cheivom." When sringaram is being dilated upon, can Geeta Govindam be left behind, particularly in a session on 'Invoking Radha' the epitome of the sringar heroine in Jayadeva's poem? Taking the ashtapadi "Sakhihe keshi mathanamudaram" Odissi dancer Sharmila Biswas stole the thunder with her presentation. Given the springboard of Srijai's singing in Misra Sarang, here was smitten Radha fantasising in her mind or reliving her first moments of total surrender to Krishna's love in the prathama samagam episode as related to the sakhi in her deep passion for Krishna. One found the rhythm of that encounter of love suggested beautifully in the 'charana rinathamani nupura' line. It was in the joy of love without a hint of self consciousness in the portrayal that spoke of the dancer's maturity. Radha returns to her real world as the Gopi engaged in the household routine of churning the buttermilk. The second part of this session had Vidhya Subramanian in a brief vipralambha followed by sambhoga sringar, in her interpretation of the ashtapadi "Kuruyadu nandana" with Murali Parthasarathy providing the music. An involved presentation notwithstanding, one felt that the interpretation did not uniformly capture the dominant emotion of abandoned contentment of an 'after love' situation this composition dilates upon. Here Radha, glorying in Krishna's love, is different from one trying to woo him. Gender is a very significant part of sringar presentation and the male dancer presenting a dominantly nayika oriented repertoire, has raised several questions. Vaibhav Arekar gave a peep into his experience with theatre and how he found it imperative to understand the essence of gender which demands a process of depersonalizing oneself and being able to feel that space within one, which is a yearning beyond superficial male/female differences. After all, love poetry picturing the nayika has been written mostly by male poets, and one has to internally traverse that journey. Love calls for total surrender, experiencing a space where the performer's gender ceases to matter. Just through the interpretation of the Ardhanariswar sloka, he showed how in just a walk the male/female in one combined entity could be suggested. 'Dance itself is sringar', he said and male dancers have no need to get trapped in dwandhwa, while presenting sringar in the female perspective. Gender fluidity in mystic poetry of the Alwars in Anita Ratnam's 'Drowning in bliss: a performative paper' lucidly brought out how the deep yearning of these poets presented a wide ranging human experience evoking nirguna, saguna, erotic, the metaphysical, had these seekers slip in and out of gender identities. When Europe was still going through its dark ages, the Indian mind registered its yearning for the ultimate. Following the Jains and Buddhists were the Saiva Nayanmar saints who in turn were overtaken by the Alwars whose experience of divinity was different from the ascetic quality of Saivism. Alwars who came from all walks of life and castes, visualised their God in varied forms - as a child in (6th century) talaatu songs of Perialwar (any influence of the Baby Christ image, the speaker wondered). If Tirumangai Alwar's songs portray love mad men (maadal oorudal), 8th century Nammalwar's 'Podu nambi' is a nindastuti. Nammalwar in a female vesham as parankusha nayika addresses parrot as the messenger of love. As males appropriated female voices, Anita mentioned other cross gender examples like Perumal's cross dressing with a fully bejewelled plait and Nammalwar portrayed as Mohini. The power above as the one Purusha with all who seek him as female was found in Sufi poetry, and in the poetry of Bulle Shah. The only woman Alwar, Andal in her poetry as a fully liberated woman, not afraid to declare her love, declares in her anguished desire of plucking her breast and throwing them 'at that dolt Ranganatha.' The very minimal expression in what Anita demonstrated seemed too quiet to substantiate her talk. What a persuasive speaker Arundhati Subramaniam is! Along with Alarmel Valli in the session of 'Atimoham - The Sensual and the Sacred in Metaphor and Movement,' she spoke of how rather than the 'cultural ivory tower' of the varnam, she had been drawn to the deep yearning for completeness expressed in Bhakti poetry, which in its fiercely individualistic tone comprises very personal journeys where the body becomes the moving temple. As she has said in her book 'Eating God,' "bhakti is not just starry eyed song and comfort food" or spineless surrender. Flesh and spirit are not in opposition in this yearning which looks at 'God not as our Boss but as our birthright' - a search in which potters, cobblers, domestic servants, weavers have all participated as unlicensed seekers. Arundhati read out an English translation of an Annamacharya poem by Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, wherein the seeker/sought relationship seems to slip in and out of polarities constantly. Little could be made of the video screened of Valli's interpretation of one of the poems Arundhati and she worked at together. One valued this session just for the way both spoke of this elusive state called bhakti sringar. The language of love has many tongues and to hear 'Kadalin Mozhi' through the cascading Tamil deluge of Kaviperarasu Vairamuthu was an experience in itself. Burning eagerness to hear from the beloved turns the postman into your God! Love makes the breeze play and the moon shine brighter. Raining quotes from Auvaiyar and Valluvar's Tirukkural, he mentioned Andal as the one poet who was experiencing love herself and not imagining it. Drawing on a planchette board, seeking answers to whether she will ultimately marry the man of her dreams, the woman does not complete the last move - lest she get an unsatisfactory answer. So she leaves it to imagination. Better to live in hope. Bharatiyar's quote had the answer to the question of why the theme of love was so completely woven round the woman. When woman can satiate all the five senses, why look elsewhere? Vairamuthu ended with a puzzling statement that Aabhas (vulgarity) can become art and not the other way round - did he mean that even vulgarity could be portrayed in an artistic way but that art should not become vulgar? Much was expected from Lakshmi Viswanathan's talk on 'Wit and humour in the world of Sringaram.' While half an hour (she exceeded the time limit by over ten minutes) is too brief for any detailed treatment, one hoped that a couple of lyrics like "Enthati kuluke" in Kalyani where the nayika scoffs at that strutting loud roué on the street (with whom she has shared intimacy) trying to attract attention, singing in flat tones, could have been interpreted in greater detail. Lakshmi's examples included passage from Krishna Karnamritam, lyrics like "Aduvum Solluval," Parvathy being chided by her mother for losing her heart to Shuddha paitiyakkaaran Gangadharan in "Ettai kandu ichhai kondai magale," a ninda stuti and the Surutti composition "Indendu vaccitivira." She spoke of the need to maintain the sthayi bhava while presenting these lyrics with their subtexts of subtle humour, wit and irony. At times, one felt Lakshmi was solely addressing 'the youngsters at the back', for the weight of how her abhinaya is capable of subtly bringing out all shades of a mood, was missing. And most surprising were the singers who were not at their best. One could not understand the purpose of Sid Sriram going into a kutcheri style of singing. That he is a fine singer gifted with a melodious voice goes without doubt. But he was supposed to deal with 'Musicality in Sringaram', where one expected to hear about the musical treatment of the clearly enunciated sahitya and raga bhava while dealing with sringaram. More baffling was the abhinaya by his sister, who could not relax and her interpretation of sringar seemed almost stern. And Rajika Puri while presenting 'Impromptu - Improvisation and Spontaneity' seemed to confuse even more. What Nithya Pillai's presentation of "Asaimukham" in Jaunpuri, Srividya Sailesh's performance of "Netrandinerattile" in Husseni and Harinie Jeevitha's presentation of "Teruvil Vaarano" in Kamas, with the excellent vocal support of Radha Badri, comprised were structured and rehearsed performances, worked out by the young dancers themselves - not on-the-spot manodharma improvisation, which is different - which the title suggested. One nevertheless wishes the bright youngsters a successful future. Very informative, witty and with that light hearted irreverence, V. Sriram's 'Sringaram though the eyes of Saint Tyagaraja' came as a breath of fresh air. He was amused that Tyagaraja's disciples, all from orthodox Brahmin families, and history had painted this Vaggayekarar as an intense Rama bhakta, without a shred of carnal sringaram in his veins. For V. Sriram, a close look at the way Rama is described in his songs like "Sogasujoodatarama" (Kannadagowla) or a keertanai like "Nee muddu momu joopave" (Kamalamanohari) or "Manasu nilpa shakti lekhapode" (Abhogi), clearly showed from the effulgent physicality of description that this man was not a dry sringaramless bhakta. In "Enta muddo enta sogaso" (Bindumalini) or "Sringarinchukoni" (Suratti) with its elaborate description of the gopis sporting with Krishna show that Tyagaraja was like any average normal householder, gifted with an enormous talent and making his compositions out to be only bhakti soaked, is a distortion. As a matter of fact the speaker wanted to know why Tyagaraja's Nauka Charitram had not been interpreted by dancers as a prime example of sringaram in all its facets. These songs had been studiously kept away from the concert circuit by singers. After Tyagaraja passed away in 1847, Harikatha experts in attempts to make the Tygaraja narrative interesting had brought in all the anecdotes on Tyagaraja's feats - not based on truth. Ironically, it was Nagaratnamma who proudly proclaimed her Devaradiyar status with the assertion that her 'dharma was sringaram' and who with pride occupied a seat beside the Harikatha wizard Soolamangalam Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar, through her own wealth built a Samadhi for Tyagaraja and worked hard to reconcile warring groups to make the Aradhana in his birthplace a regular event. 'Is Sringaram relevant today, the Big Debate' had Bragha Bessel, Sheela Unnikrishnan, Rajeswari Sainath, Aniruddha Knight, Dr. Swarnamalya Ganesh, with Srinidhi moderating. When Sainath brought in the hackneyed argument of social issues being dealt with in the dance instead of sringaram, Aniruddha Knight responded by saying that if he wanted to be informed on social issues, he would look at the daily papers -rather than look for this in Bharatanatyam. The eternal question of whether to revisit traditional items or present something new came up. The deliberations digressed into teaching youngsters and what have you, which was not part of the debate. Very predictably the argument for Sringaram won the day. It was an interesting blend of sugar and spice that Natya Kala Conference badly needed. .  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Response That was a nice outlook of the Natya Kala Conference 2017. Just thought would contribute to thoughts and values that came forth through the seminar. These thoughts are after watching the online edition. Well, to begin with, anything that is beautiful to the eye brings in joy and happiness. It is sringara rasa that is associated with words like beauty, happiness, like, love, joy etc. "Sringara is Beauty or Saundarya. Beauty is that which attracts the mind or appeals to a particular penchant of the mind. That is love." Thus appreciation of something beautiful is like sringara rasa has developed in the mind of the appreciator. Then, even, if ideas spits of raudra and bhibhatsa, the stylized presentation of classical art helps bring out beauty to the whole show. Thus too, the sringara rasa becomes substratum of all rasas. Thereby, sringaram is the King of rasas. And "Love is not just Rati the amorous attitude. There can be love between a child and its mother, between friends, between a teacher and disciples and of course love towards God." Here, in this conference, sringaram has been associated with love between two individuals - between man and woman. Guru Sadanam Balakrishnan said, adhering to the stylized presentation as prescribed in the Natyasastra helps the Kathakali form to show sringara in a way all can watch with their family. In his lecture, Devdutt Pattanaik says - one needs an another to understand oneself, for every seeker there is one to be sought, only union of these two helps the problem of knowing oneself, which means merging of two entities/ opposites is a must. This means that to understand sringara rasa, union of two individuals is a requisite. And in dance too sringara rasa becomes the edifice - where, it is normally shown the female as being seeker and the male as being sought. According to a renowned artiste, this could be because a female expresses her love with more intensity than a male. While there is a continuum of sringara lahiri, earlier traditions were subtle, dignified and implicit; while today dancing is subtle, dignified and explicit. And yes, today teachers are teaching only that which is required to perform on stage at a given performance. This is like going back to those days before Tanjore Quartet codified adavus and created the margam presentation. When Quartet brothers choreographed the margam they presented structured items that had a grammar to it; they themselves composed the required music for it. They have set bar for new compositions and items (both music and dance) to be presented. The new generation should go through these structured items and grammar underlying them before composing newly structured items and presentations. Structure and grammar is what defines a classical art. Now, it has sunk in - that mostly all poems have been written by male poets, and that, while writing their poems in praise of their chosen Lord have considered themselves as 'nayikas'. This phenomenon must be in keeping with Indian philosophy that all souls whether embodied in a female or male body is considered as 'prakriti' in form and addressed in female gender as compared to 'purusha' which is spoken of in male gender. Surely and soon a way to perform without donning women's character will be found, since one has to go beyond gender classification of 'prakriti', feel or experience within self and express his/her ideas and values. Another example is from Natyashastra where sthanakas - standing positions - are given as 5 for male and 3 for female. What we can see is that Lord Rama and Lord Muruga are represented using female standing positions and Goddess Kali using male standing position. It is essential to go beyond this gender like classification and understand that male stanakas are for strong ferocious characters and female ones are for gentle characters. This classification label again indicates to dogmatic norms of upbringing that women should possess gentle characteristics while men should possess a strong disposition. For example: that girls can cry but boys should not. If we rise above this view, then men dancers could also show their feelings and love for the sought intensely, and does not have to feel like they are portraying female sensibilities. Finally adavus themselves are very neutral in character. One can see this in the item Ardhanareeshwar by Vaibhav Arekar. He characterized Shiva's dance with strong movements and characterized Parvathi's dance with graceful movements. But when he himself danced the demarcation was clear, he was dancing as he approached the adavus and not a hint of Lord Shiva's characteristic dance was seen. It doesn't matter who dances as long as dance is personified. Earlier also it was nattuvanars who were of male gender who taught girls to dance. It was their individualistic idea of beauty that created the style of the dancer and the art form. Nice way of presenting bhakti sringara. Breaking off from jivatma paramatma concept was done superbly. The best point was to suggest one refrains from giving a "pati parmeshwar hai" (Hindi term) attitude while dealing with the traditional varnam. Hope the lecture could be translated in vernacular language for those who learnt the art form of dance in vernacular languages. In fact, most Vedic rituals do begin by first considering the body as the abode of God. But commoners needed an object to concentrate which would help to get connected with the inner self, thus temple buildings and various idols of gods got its importance. Besides, it was understood that the concept of Jivatma and paramatma in bhakti philosophy was an easy explanation to make common people or masses understand the subtle principle of being one with inner self and evolving the self to greatness. Thus this concept helps varnam to reach out to masses too. The debate seemed to be carried forward with the idea that sringaram is an emotion that expresses intimacy between a man and a woman. If that is the case then the graded format as explained by Bragha Bessell and Sheela Unnikrishnan is the best way to train students of Bharatanatyam. But if you see sringaram as a rasa that informs or make you realize or gives relish of a truth of life, and led to experience it through universal emotions and feelings then these old songs have relevance even today. "Padari varugudu" for example seems relevant event today. In western countries they have a system of dating. When they are young they are allowed to kiss only with pecks on cheeks. As they grow they are allowed to kiss on lips. Then after they pass secondary school they are allowed invasive kisses. In fact girls and boys are encouraged by friends to experience it and discuss these with friends. And then in a graded manner they get into relationships, have multiple sex partners till they are married. Like westerners, how many folks in India go about discussing their carnal cravings and experiences with their friends? Then the song mentioned has its relevance. The song portrays universal feelings of all those in love and waiting for their partners. And the audience relates to the song and remembers their own experience of craving, their happiness on receiving gifts etc. Of course, where it is performed, by whom and for who matters; definitely not in arangetrams by youngsters. Traditions can be taught to the young through teaching-learning of Bharatanatyam. Like Bharata said, natya helps to inform, educate, pacify, encourage and also modify behavior of people. Old compositions decode lifestyles of old generations and children can imbibe them. And when new compositions are composed and choreographed, old compositions will guard and guide them in their efforts. The structure and the grammar underlying the art form will give them a frame work that aids them to present their contemporary times and be in conformity with principles of the art form. Finally, the essence of Bharatanatyam is characterized by attributes of beauty, subtlety, minimalism and dignified presentation. - Chandra Anand, Mumbai (chandra6267@yahoo.co.in / Feb 23, 2018) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |