|   |

|   |

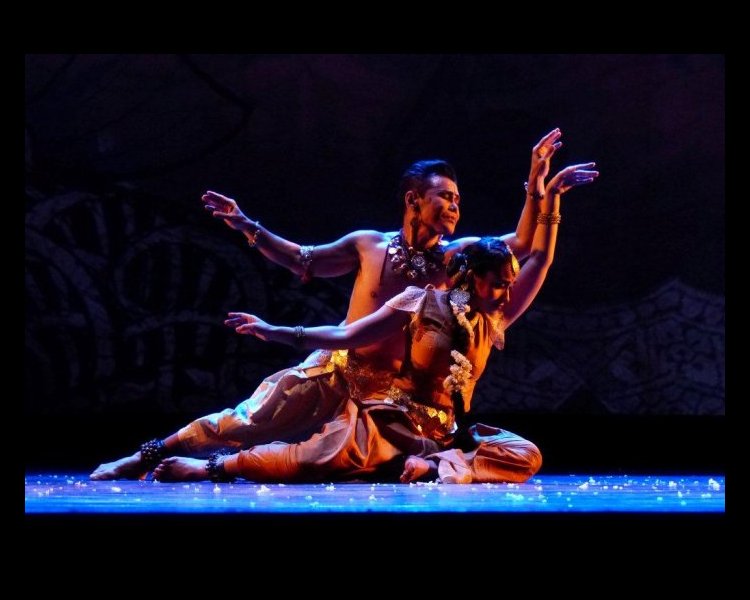

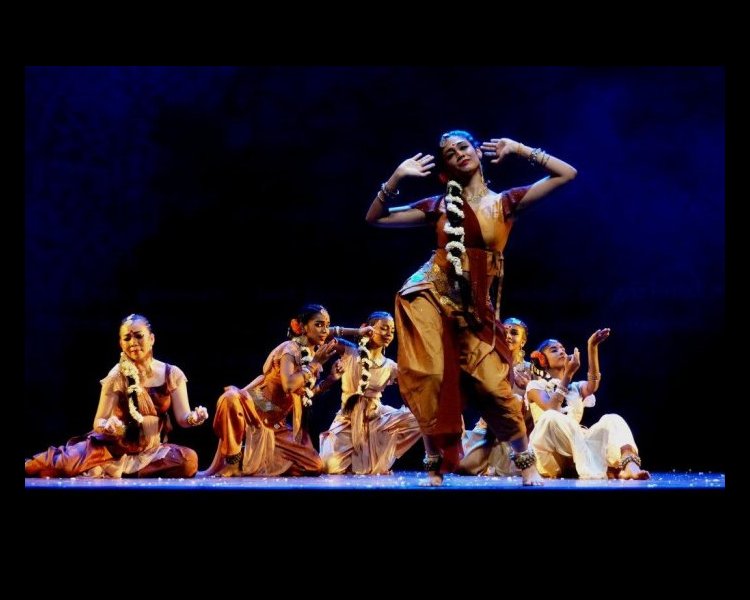

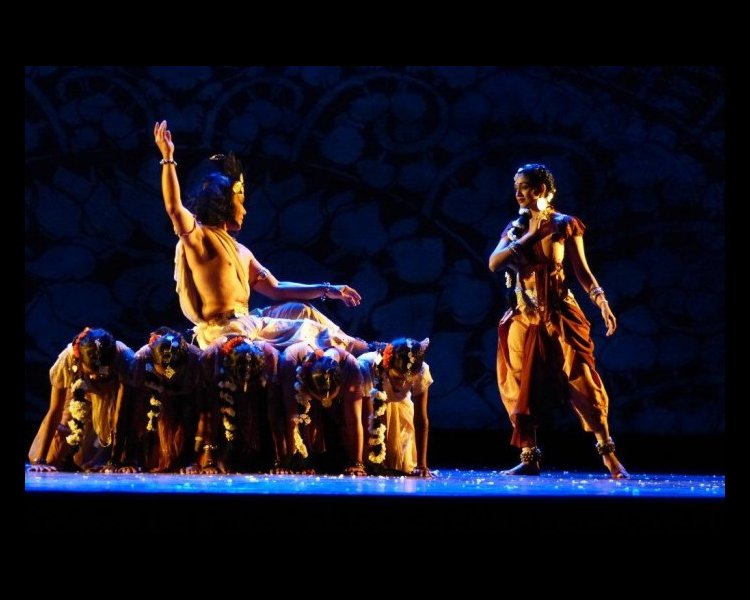

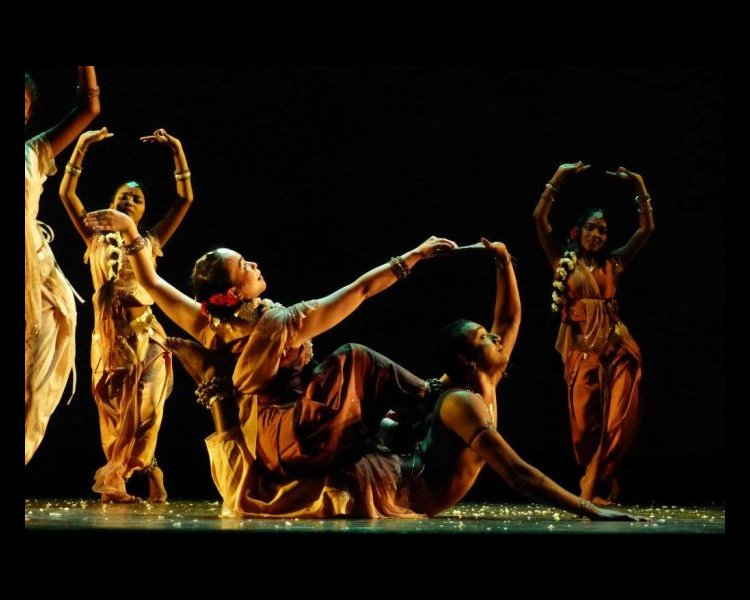

e-mail: leelakaverivenkat@gmail.com In a different tone: Amorous Delight presents a challenging theatre of love Photos: Avinash Pasricha April 18, 2017 Pickling for over a decade in the minds of Ramli Ibrahim of Kuala Lumpur's Sutra Foundation and late Dinanath Pathy, art historian / painter et al of Odisha, Sutra Foundation's Amorous Delight, a group work based on the 9th century Sanskrit love poetry Amarushatakam traces its seed inspiration to the palm leaf manuscript illustrations based on this text by the unknown Sharnakula master of Odisha's Nayagarh district, the rare copy of which in the Zurich Museum Rietberg, Ramli Ibrahim happened to see. Late Dinanath Pathy and Dr. Eberhard Fischer of the Museum had collaborated on a book jointly authored on Amarushatakam. Ruminating over the challenges of such flagrant erotic verses on sambhoga and vipralambha sringar as base for a work in what has justifiably been called 'Contemporary Odissi', Amorous Delight draws on blended creative energies from Odisha and Malaysia - with late Dinanath Pathy himself as the visual and literary consultant, and with the musical base provided by Odisha's top artistes. Working with the dancers of Sutra Foundation was Odissi dancer Meera Das whose dance composition along with Ramli Ibrahim's group choreography aesthetics with artistic direction, designed this effort. With several recensions of Amarushatakam, it is Anandavardhana, the 9th century commentator's reference to Amaru as a great poet that has made scholars ascribe this work to the 9th century. By this time, the Shatakam in Sanskrit in form and structure, as the construction of one poet, but with independent self-standing couplets without a narrative, had already been in vogue. Which is why, some scholars were inclined to think of Amarushatakam as an anthology of poems - their opinion changing after seeing the unity in structure and style running through the hundred couplets, all strung by one theme of erotic love. Later commentators were persons like Vemabhoopala and Arjunavarmadeva. The literary elegance of the poetry has encouraged the theory (based on mention in Madhava's Shankara-digvijaya) that the Amaru verses were penned by none other than Shankara who in an endeavour to experience erotic love, harnessed his yogic power of parakaya pravesha - acquiring a different corporeal frame for his soul which leaving his original body invades that of a corpse, in this case of King Amaru, resurrected temporarily to life. The production is anchored on excellent music composed by Srinivas Satpathy. Providing special touches is Guru Dhaneswar Swain's mardal (pakhawaj) rhythmics, which along with the delightfully recited ukkutas, adds an extra dimension to action with the abstract sounds, apart from providing the right punctuation linking the sahitya passages. As for the melodious quality of both male and female voices, and the recording, little is left to be desired. The first sloka "Jyakrushtivaddha katakamukha paani purushta..." sees Shiva enter with Ambika, her hand with radiant nails held in the katakamukha hasta, letting fly the flowery arrows of love on the unsuspecting maidens who fall prey to sringar. In the next scene, the angry young maiden who wants to be left alone is grabbed and the man describes the stolen kiss from her as the best of nectar, far above what was churned in the ocean for hours by the stupid Gods for nothing. In the sloka "shoonyam vasagriham vilokya.....", the young bride in the bedchamber raises herself slowly, feasting her eyes on her lord who is feigning sleep and caresses him - realizing through the pleasure reflected on his cheeks that he is indeed awake. The tender scene in "likhanaste bhoomi..." visualises the picture of the repentant man drawing pictures listlessly on the sand, sitting outside the house of the sulking nayika who is urged by her sakhis to discard her pride and banish her loneliness, which have reduced her to an emasculated state and proceed to meet her lover. Slide show Photos: Avinash Pasricha

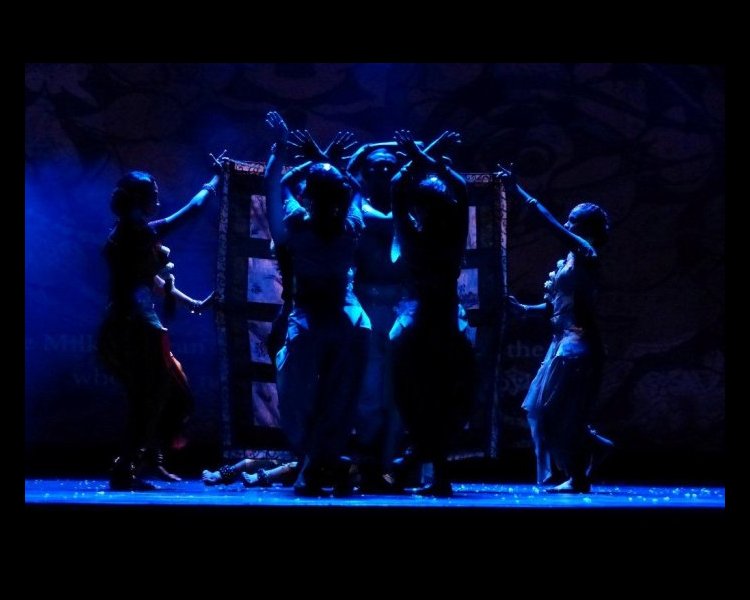

The concluding scene was the best with the narrative fashioned to expand on the sloka "Deergha vandana-maalika..." wherein the young maiden greeting the long awaited lover, garlands him with her eye glances, offering to him her whole beauteous self in total surrender. The dancer concerned, Geetika Sree with her highly expressive eyes and face, conveyed the nayika's feelings most tellingly and the scene develops with the lover walking in being welcomed by the sakhis, with a final scene of his reclining on a bed made of four kneeling dancers on all fours, in a row, with the nayika making a slow expectant entry into the bedchamber. The suggestive swaying movements of the crouching dancers (forming the bed), to the tingling bell sounds in the music, made for one of the most gripping scenes. All the dancers showed animated involvement. The other dancer who took on many of the roles was Divya Nair. Harenthiran played the main male role, with Ramli stepping in on occasions. The senior Sutra dancer Tan Mei Mei, apart from her involved dancing, was the most relaxed in the intimate scenes. The finale with Debaprasad Das' choreography of the Pallavi in Shankarabharanam provided an ending on the right note. The group scenes skillfully designed provided intricate movement frames within which the main dancers portrayed each love situation - sometimes suggesting different locales of the outer street and the inside of a home. Unfortunately, without this element, the presentation at the Kamani looked somewhat bare in comparison. The younger dancers, particularly the three young male dancers, in the Pallavi and other scenes in the Kuala Lumpur version, impressed with their clean movement profiles. When twenty bodies squat in perfect chaukas, it made for a riveting visual sight. A work like Amorous Delight, in a group form, demands a physicality in portraying the male/female relationships, which most classical dancers in India would find alien. What is part of theatre and to a large extent films, is not the convention in classical dance. In solo form, Amarushatakam couplets have been interpreted through abhinaya, and here the dancer in solo blessedness can suggest moods of erotic love. Conventional Odissi audiences would find in Amorous Delight little of the usual Odissi margam vocabulary, barring the concluding Pallavi, for the theme here of visualizing very flagrant poetry describing erotic man/woman relationships, in a host of situations, asking for a different type of treatment. Here love scenes flitting by like miniature paintings portray sringar in varied situations - of expectant hope in trysts, ecstasy in togetherness and bitterness of separations and betrayals, passing by in quick moving incidents, without any narrative running through the couplets. Besides, there is neither sermonizing nor judgemental tone in this unabashedly frank poetry. Given his Ballet and Contemporary Dance experience, Ramli Ibrahim, apart from the main Odissi base as body language, has sought ideational inspiration from the visual art of palm leaf paintings for creating certain cameo-like movement images to create theatre design, using Modern Dance lifts and weight distribution between two people while choreographing intimate scenes. While large audiences in Kuala Lumpur were thrilled by the work, the Indian response at Delhi's Kamani Auditorium on April 6, 2017, to what was presented by a restricted skeletal cast, was more restrained. "The full blown Odissi is only in the Pallavi" was a remark. This work requires an audience with an open mind. What is exemplary is the group discipline as also the aesthetically tailored and designed costumes by Bernard Chandran with wardrobe experts Nithya Kuthiah and Prithylasmi. As for the graphics as a backdrop while action is going on and the remarkable lighting by Sivarajah Natarajan, this becomes crucial to a work made up of the fading out and coming in of several unconnected scenes, investing the work with high marks for production values.  Writing on the dance scene for the last forty years, Leela Venkataraman's incisive comments on performances of all dance forms, participation in dance discussions both in India and abroad, and as a regular contributor to Hindu Friday Review, journals like Sruti and Nartanam, makes her voice respected for its balanced critiquing. She is the author of several books like Indian Classical dance: Tradition in Transition, Classical Dance in India and Indian Classical dance: The Renaissance and Beyond. Comments * Beautifully written review, beautiful photos, shows so much research, creativity and thought..... bravo Ramli, Leela, Avinash, thank you all for sharing this. I hope I will see it some day. - Uttara Asha Coorlawala (April 20, 2017) Post your comments Please provide your name and email id when you use the Anonymous profile in the blog to post a comment. All appropriate comments posted with name & email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |