|

|

|

|

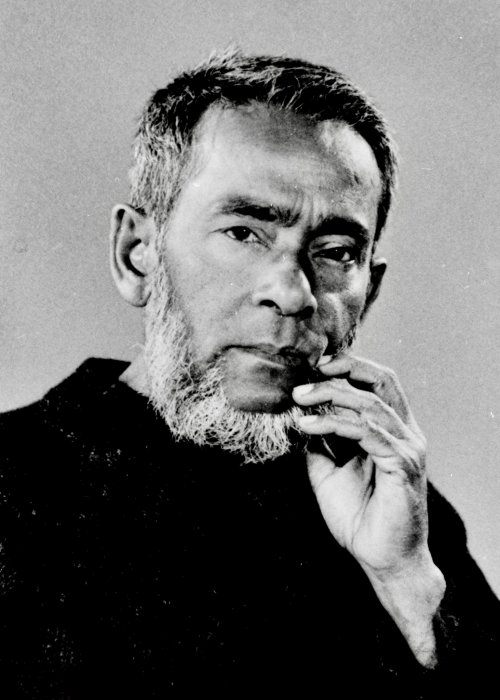

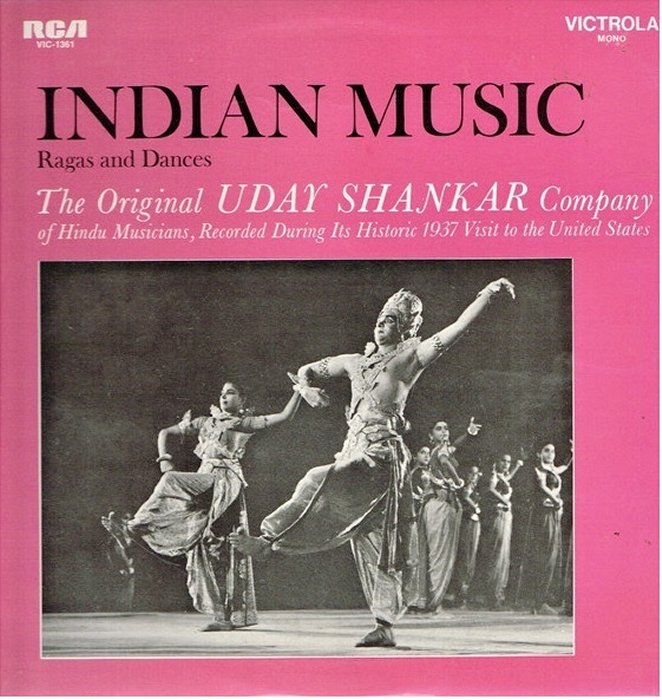

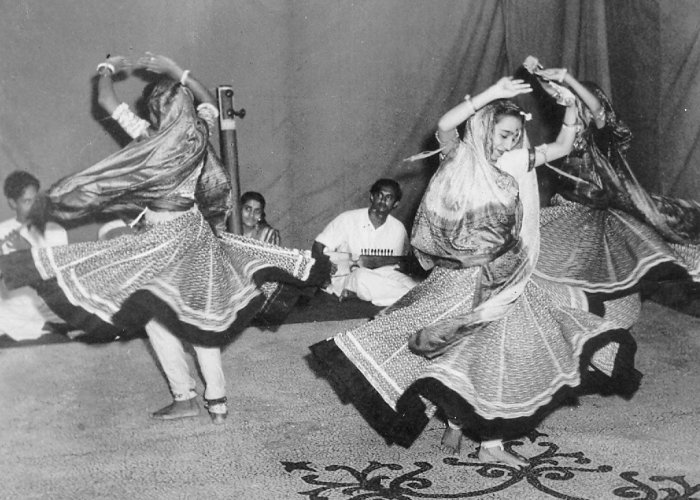

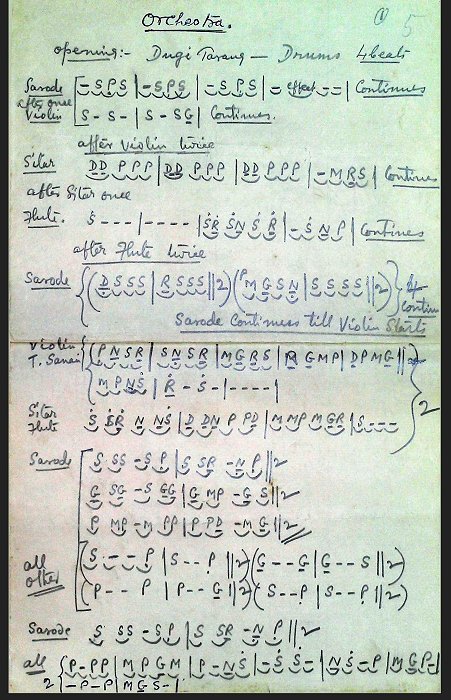

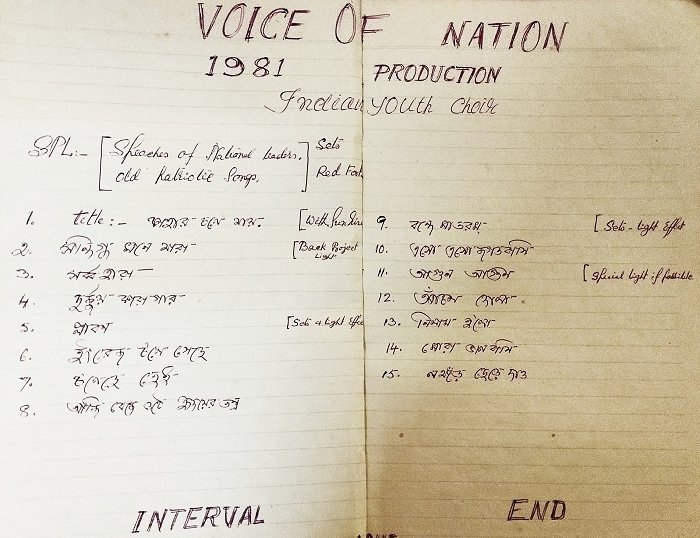

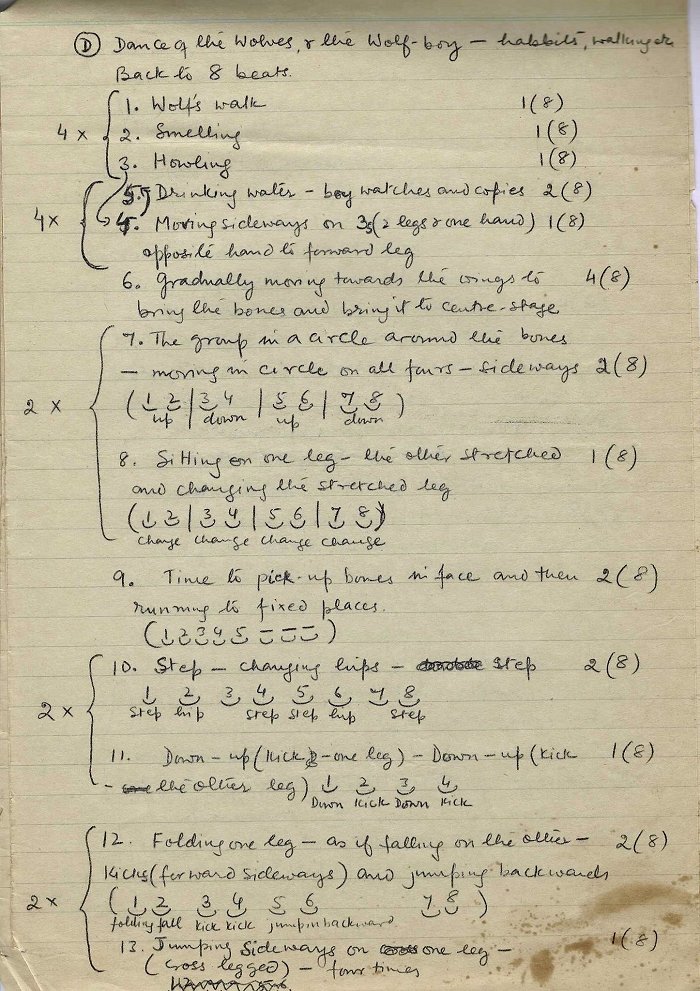

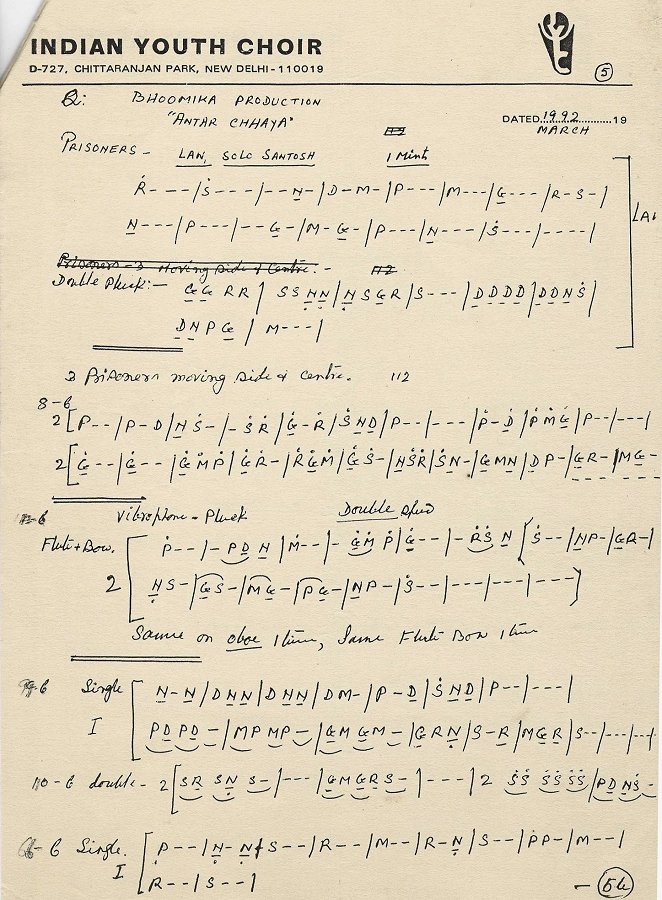

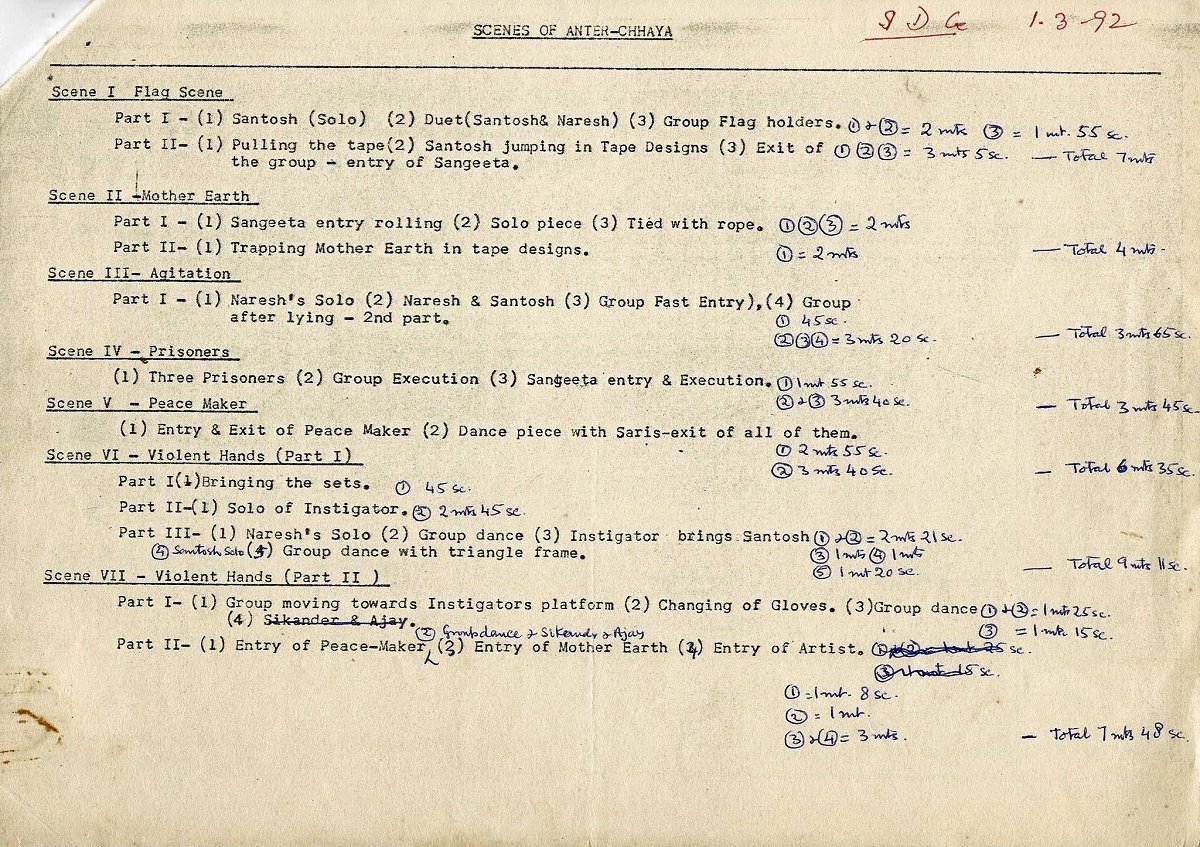

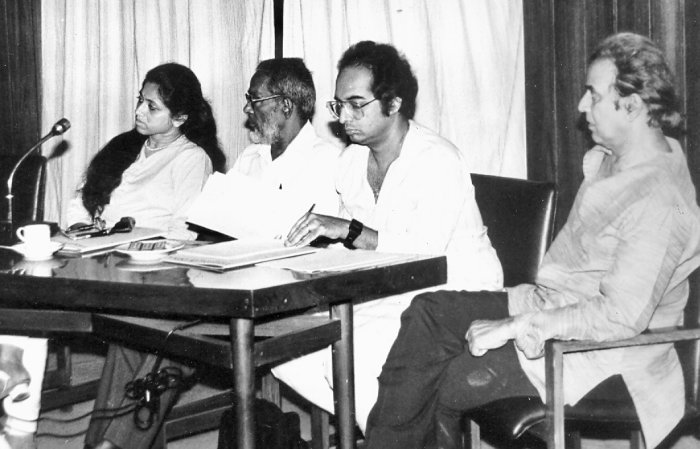

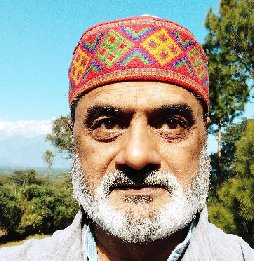

On the 17th Death Anniversary of Sushil Dasgupta (1923-2008) - Bharat Sharma e-mail: bhasha.dance @gmail.com Photos courtesy: Narendra Sharma Archives March 14, 2024 FROM NARENDRA SHARMA ARCHIVES From time immemorial, Music and Dance have an intimate relationship - one lives on the other in performing arts. In the 20th century, composers and choreographers shared a tenuous relationship in stimulating fresh trends in dance-making - both in the East and the West.  Sushil Dasgupta This post looks into a particular thread of music-making which evolved on Indian sub-continent, within the expansive 'nationalist/post-colonial' discourse, based on Indian instruments, voice culture, 'swara' of 'raga', intricate 'tala' system, and deeply embedded within the ethos of indigenous melodies and orchestration. A kind of 'new tradition' came into being, emanating from the ingenuity of their creators. In particular I would like to project the work of Sushil Dasgupta - a music composer par excellence - who became the longest collaborator of choreographer Narendra Sharma, with beginnings that can be tracked back to 1946. Today the term that has come into vogue is 'World Music', more in terms of post-war responses by musicians to 'multi-culturalism', travel, migration, technology, and the attractions of burgeoning Global Music Industry. The foundational principle of this genre was to recognize 'difference' between non-European/Western systems of music-making, and myriad 'traditions' of the East, especially 'differentiated' Asia. However, the genesis of this phenomena lies somewhere else, especially to developments 'between the two World Wars'. In case of India too, virtually every 'revival' movement in performing arts has to track back to first half of 20th century. To begin with, let us listen to the music of a forgotten maestro, who could be considered the Father of 'Indian Orchestra' - Timir Baran. Immaterially this takes us back to the seminal work of Uday Shankar in mid-20's, spurring new benchmarks of collaboration between choreographers and composers. This time it was both Ustad Allauddin Khan and his protegee Timir Baran Bhattacharya, sarod players of highest order, who turned to composing, working in tandem to give a musical aura to Shankar's dances that were still evolving on Indian soil, before getting transported to Paris to be presented at Theatre des Champs-Elysees, pretty much the center of cultural capital of the West of that era. Ground work for this was laid by Shankar himself. During his travels in Indian sub-continent with Alice Boner, the Swiss sculptress and his manager, he had collected a range of native instruments that he began experimenting with, to evolve music compositions for his dances in India, and later in Paris, before the dance company's block-buster debut in March 1931. Within the entourage of Uday Shankar's music ensemble were many stalwarts. Along with Timir Baran and Allauddin Khan was Vishnudass Shirali - a student of Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. And the presence of his younger brother Ravi Shankar, 20 years his junior, who had still not decided whether to be a dancer or a musician. Shirali ji can be credited for 'inventing' the 'tabla tarang' - of tuning the 'baayan' of 'tabla' into a scale of 'raga', and then making it an independent instrument of playing in concerts. The new music that emerged was path-breaking. Anybody interested can listen to the RCA produced album of Uday Shankar Dance Company's music during his tour to the US. All ingredients of 'Indian Orchestra' were already in place...this was Shirali ji's creative peak as a composer. There is a solo rendition of his in the album on 'tabla tarang' - which was played later in 60s by composer Kamlesh Moitra.  RCA album, USA Earlier, it was Timir Baran's genius that laid the foundation for orchestration - the structure, combination of instruments, the melodies based on 'ragas', variations of 'talas', and the dramatization of thematic contents. The fading out of this genius, through his problematic relation with film actress Sadhna Bose, is a separate matter of enquiry. He had moved to Mumbai films, and his compositions for film 'Rajnartaki' (1941) and other orchestral works (available on YouTube) are still haunting, and fodder for any contemporary musicologist who may want to study outside the 'gharana' system of Hindustani music. Vishnudass Shirali was the person who took up the baton after Allauddin Khan left Uday Shankar's group to begin his teachings at Maihar in Madhya Pradesh. Shirali ji became the prime mover of orchestra at Shankar's center at Almora (1939-43) - South Asia's first School of Choreography. At Almora, Uday Shankar - fondly called Dada by his students - put together a dazzling group of talents from all disciplines of performing and visual arts when he began. He spent days travelling all over the sub-continent to select and invite them to join his 'tryst with destiny' in the foothills of Himalayas in Kumaon region - this center for innovation, and the trials and tribulations of making/unmaking of the institution, is subtly etched in his semi-autobiographical magnum opus film 'Kalpana', with an extraordinary music track composed by Shirali ji in Gemini Studio in Chennai. Much has been talked about Dada's film 'Kalpana', and its influence on the making of box-office hit 'Chandralekha' and impact on Tamil cinema, or for that matter extra-ordinary cinematography/scenography, or its recent restoration and resurrection at international level, and much else... But it is still a paradox that little has been talked about Shirali ji's extra-ordinary music for this film, especially his orchestration, choral renderings, songs, combination of instruments, voice modulations, and gibberish. His music for the dream sequence is a masterpiece, carrying his signature 'tabla tarang'. And the patriotic song 'Bharat Jai Jan' (with lyrics by Sumitranandan Pant), should be sung in every school in this era of hyper-nationalism. This unassuming gentleman was born in 1913 in Hubli, close to Dharwad, one of the most prolific regions of Hindustani music. Shirali ji's contributions have still not been claimed by both Karnataka or Maharashtra, given the disputed cultural territory stuck between the two states after the state re-organization after Independence. It's a sad commentary of arts scholarship we have evolved for ourselves, and the uneven recognition of artists therein.  Abani Dasgupta Yet another exceptional multi-faceted talent Dada recruited for his orchestra was Abani Dasgupta, whom he heard playing 'dhak' during an interlude of theatre performance in Kolkata. Born in 1913 in a village in Badisal district of erstwhile East Bengal (now Bangladesh), Abani da moved to Almora with his wife. His first child, daughter Shila Mukherjee, was born there. Abani da played multiple roles - as an adept sculptor he made statues for Durga 'puja' every year at Almora, and carved out new musical instruments of wood extracted from forests of Simtola. He invented the 'saranda', a larger version of esraj/sarangi, which replaced the role of base notes of cello, to the 'raga' scales of Hindustani music.    Music instruments at Almora In an atmosphere of constant innovation at Almora, the students were encouraged to choreograph new dances from the word go. In the evening, entire live orchestra would sit together in a corner of the large wooden studio to improvise in Dada's composition classes. As a result, almost all musicians, trained in Hindustani music and even Carnatic music, began experimenting. Musical instruments were in plenty - Dada had a phenomenal collection that he had collected during his tours that were nicely stacked along one wall of the Studio 3. Musicians would often pick one and accompany the improvisations on floor. As such, all musicians were slowly becoming composers. Another talented musician in the entourage was Jiten Gului, and he collaborated with Baba (my father) in making his everlasting masterpiece - 'Flying Cranes' (1940). As it happened, the traumatic winding up of the Almora Centre in 1943 had many sub-texts in the music world too. While Ustad Allauddin Khan had retired to Maihar to train a generation of greatest soloists of the 20th century, he also set up the Maihar Band by training ordinary citizens picked up from the subaltern class of the town. Ravi Shankar had abandoned his career as dancer to begin intense training in sitar in Maihar. Shirali ji, with a handful of musicians, headed for Gemini Studio to work on sound track of film 'Kalpana', carrying with them a vast body of instruments from Almora. I am in doubt, whether there are any records on the process on how the music was composed, although compositions for many dances were already in place at Almora, as well as for Dada's tours abroad. IN MUMBAI Abani Dasgupta, with his family, headed from Almora to Mumbai to seek employment. His talent as a seasoned percussionist was immediately recognized by many composers in Mumbai film industry, especially of the 'Bengal School', including Hemant Mukherjee and Sachin Deb Burman. His income became steady, and was one the earliest to set up home. His 'kholi' was to became an 'adda' for many young bachelors who were yet to arrive to look for work in Mumbai in mid-40s. There were separate rooms for his professional work - for sculpting and making new instruments. I often visited his studio in my teens, and saw him with his hammer and chisel in hand, pounding at woodblocks, relishing in inventing new instruments. But soon he was to emerge as a brilliant composer in his own right - pretty much carrying forward the torch of 'Indian Orchestra'. While Zohra and Kameshwar Segal, Guru Dutt, Sardar Malik, Simkie and Prabhat Ganguly, Ravi and Annapurna Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan and his sons, and many others from Almora arrived in Mumbai, the financial capital, to work in films and otherwise, another development was to take a fascinating turn around Borivili. P.C. Joshi, then General Secretary of united Communist Party of India, invited Shanti Bardhan from Tripura, and a former dancer of Shankar's company at Almora, to set up a professional dance company and choreograph 'India Immortal' under the banner of Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA). This production, a kind of agit-prop ballet against British Imperialism, was to travel from Lahore to Kolkata as part of rising nationalist fervor after declaration of Quit India in 1942. Shanti da invited Sachin Shankar and Narendra Sharma, again products of Almora school, to assist him in choreography for 'India Immortal', and Ravi Shankar was called upon to compose music. Abani Dasgupta and others had already joined beforehand. But for a large live orchestra, they were still short of hands. As such, Abani da called upon his younger brother, Sushil Dasgupta, from his village Pirojpur in East Bengal. Sushil da played flute, and upon arrival in Mumbai he was quickly absorbed under the baton of Ravi Shankar at IPTA at Khusrau Lodge, where the rehearsals had shifted. This collective fervor was charged by creative outpourings - dance, choral singing, orchestra, poetry and theatrical renderings. This 'Indian Orchestra', gave umpteen live performances accompanying the 'Indian Ballet' - carrying bulk of instruments to all venues along the journey. It was at Central Squad that Baba and Sushil da first met in 1946, and a partnership of sorts was to evolve gradually, between the choreographer and the composer, that was to last their lifetimes in most unusual and checkered ways. This collaboration flowered to the full extent when both shifted to Delhi between 1954-55. However, it will be important to interject here to illustrate a bit more on the contours of 'Indian Orchestra' that had crystallized by then. Once the nascent film technology got entrenched in Mumbai industry, studios began multiplying, films graduated from silent era to talkies, star system came into place, writers and lyricists began to find work. Film industry became the biggest employer of artists. In music studios, there were musicians trained in Western classical music, adept at playing by reading 'Staff Notation' - players of violins, clarinet, saxophone, cello and other instruments were aplenty. But for the 'Indian Orchestra', a fierce determination was to use Indian instruments and Indian melodies - folk and classical, 'ragas' and 'talas', and commensurate harmonics, if any. How did this 'Indian Orchestra' work for live performances? Most composers had already developed an indigenous system of notation which had nothing to do with western 'Staff Notation' - adapting mostly the Vishnu Digambar Bhatkhande system - with the symbols/alphabets ('swaras'), beat/markings ('matras'), noting for each instrument, and innovations developed by each composer that could be 'read' by multiple musicians and singers in the orchestra. This was necessary, as many performances went over two hours, and it was not easy for all to remember long compositions. There were separate notations for string, bow, wind and percussion instruments, and yet other noting for songs and lyrics. Virtually every composer was adept at both - orchestration and choral singing. Yet another important facet was that choreographers and composers worked in tandem in rehearsal hall, in real time - a movement/dance pattern would evolve, and music would be composed there and then. Once the themes or stories were decided upon, composers and choreographers discussed broad outlines and flow of scenes. A rough script/storyboard was often made beforehand for mutual clarity, and details were worked out on the floor. This is a facet which has not been recognized in full, even today - this was unique in terms of both the method adopted in film industry, where songs and dance sequences were recorded first with lyrics, and dance 'masters' were asked to 'supply' dancers and movements on the Director's diktats on studio floors, or for that matter western classical systems where the music was composed first, and choreographers interpreted the score thereafter in Classical Ballet. Most fascinating part of this enterprise was the choice of instruments, a pattern that had slowly emerged over the years - sarod, sitar, flute, and often esraj, were mainstay for melodies. But the most elaborate side of an orchestra pit was the percussion section. Each percussion unit had a range - nagara, duggi tarang, tasha, tabla tarang, jal tarang, khol, dholak, naal, tabla, wooden tik-toks, jhanj, gongs, manjira, kadtaals, and what not...Most were made of brass or wood, and often packed and carried in large wooden crates from one performance to next. Harmonium was used only for composing or to accompany the singers. Perfection in coordination was achieved only by hours and hours of rehearsals on floor, along with a handsome package of memory bank of musicians! Yet another aspect that needs to be borne in mind is the technology that had entered the performance space in those times. Gone were the days when musicians played in intimate environments of palaces or durbars. Concerts were now having microphones and speaker systems to amplify the sounds and voices in large/open spaces. Music pits had elaborate arrangements and demarcations of seating to project the collective sound of orchestra - vocalists in front, sarod, sitar, flute and esraj close by, and the expansive percussion ensemble at the farthest end, given its scale and volume of the renderings. The composers often sat in the middle in front to conduct the orchestra, with the entire set of notations in front. In earlier stages, the music pit was behind dancers on stage, but later they mostly occupied the downstage right area. Another facet was that all musicians were trained in Hindustani music - self-trained or trained under a guru. Some learnt music as apprentices in groups, from scratch under composers. Most were able to 'read' the notation that was given to them - the Bhatkhande system of 'Indian Notation' - and could play highly structured compositions to the last detail. And there was a whole range, in large numbers, who were available to composers for decades...in several cities - Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Gwalior, Bhopal, and many more... Before I elaborate on Sushil da's method as composer, let me first return to the collaboration of Baba and Sushil da in Mumbai. Once the Central Squad of IPTA was disbanded in 1946 due to economic, political and personal reasons, there were multiple splits in several directions. Two offshoots that emerged out of the group were the setting up of two separate dance companies - New Stage and Little Ballet Troupe (LBT). The former was a partnership between Sachin Shankar and Narendra Sharma, and the latter between Shanti Bardhan and Gul (Jhaveri) Bardhan. Abani Dasgupta became the music director of the latter, and Sushil Dasgupta of the former. Most interestingly, Abani Dasgupta at the LBT in Mumbai (1952-53) composed the original version of Shanti da's seminal masterpiece, ballet 'Ramayana'. After the tragic demise of Shanti da due to ill health (he was unable to recover from a bout of Tuberculosis), the dance company began its winding journey from Mumbai, to Gwalior, to Bhopal. Abani da preferred to stay back in Mumbai, because he continued to get work in the film industry. But LBT carried the entire bulk of musical instruments of the orchestra with them all along their arduous journey. Today a whole range of those instruments can still be seen in their museum in Bhopal at Shamla Hills. LBT also had a privilege to having a range of composers working for them all along, including Vishnudass Shirali, Bahadur Hussein Khan, Ranu Bardhan and later Sushil Dasgupta himself.  Performance of New Stage with musicians at back with my mother as singer (1950) In case of New Stage, Sushil da set up yet another orchestra with new set of instruments and musicians in Mumbai. In this case, there were not many long ballets, but a range of shorter dances, with a flexibility for choreographers to put together variable programmes, needed for specific venues. Within a few years, this group also split, but before the artists went their own ways, they succumbed to romance in the air. Most found their spouses within this group - Sachin da married Kumudini Lele (an actress from Marathi films), Baba married Jayanti Sodah (singer who migrated from Karachi after the Partition), and Sushil da married Vittal Radha Bhat from a village near Mangalore. She became Anuradha Dasgupta after marriage. What amazing 'multi-cultural' partners they turned out to be in subsequent decades!! IN DELHI Once Baba quit Mumbai and film industry for good, he re-located and settled in Modern School to begin his career in Delhi (1954), the capital city of India which was just emerging out of the euphoria of Freedom, and the trauma of Partition. While working in Modern School with children, he set up a separate dance group to carry forward on professional front - Delhi Ballet Group in 1955, which was re-christened National Ballet Centre in 1957. This was done to give performances for international delegations, national festivals and tourist destinations. Baba re-transported the entire batch of musical instruments accumulated for New Stage, in wooden crates from Mumbai to Delhi, for Sushil da to pick up the baton yet again as music director of all his dances.  Sushil da's notation for one of the dances for New Stage Sushil da also became part of a remarkable bunch of composers that had settled then in Delhi, including Jyotindra Moitra and Benoy Roy (Manager, Central Squad, IPTA Mumbai). All of them got commissioned regularly by the Film Division, who churned out documentaries to mark events of political and cultural significance. This was preceded by Ravi Shankar (1949-56) who led the National Orchestra at All India Radio (AIR) that gave employment to a range of musicians. Each Sunday morning, AIR broadcasted new compositions of the 'Vadya Vrinda', which was pretty much the extension of 'Indian Orchestra' in the national capital which I grew up with.  Indian Youth Choir, AIFACS  Program for Indian Youth Choir, AIFACS Sushil da's career became prolific over the decades. He was a master conductor - precise and meticulous - he could organize a large orchestra with ease. He evolved short orchestral pieces which began as overtures to an event or got interspersed in longer performances. He set up one of the earliest choral groups in Delhi - Indian Youth Choir - which trained young singers in patriotic songs in Bengali and Hindustani, and was active till his last days. From 1956-76, he worked for Children's Little Theatre (CLT) of Delhi, making music for ballets and composing songs for children. He soon began composing large Operas for theatre groups in Delhi - 'Heer Ranjah' (1958) in Punjabi for Sheila Bhatia's Delhi Art Theatre was a critical success with Snehlata Sanyal and Nishi Nakra as main protagonists. In 60s and 70s, he composed several Jatras (folk operas) in Bengali. For Song and Drama Division of Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, he composed for ballet 'Nai Usha-Nai Disha', and for the light and sound show 'Vidya Pati'. In 1955, he toured as flutist with Little Ballet Troupe (with their ballets 'Ramayana' and 'Panchatantra') and Shirin Vajifdar's group to China during the peak of 'Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai' era...Later, he was given the Sahitya Kala Parishad Award by Delhi .  Sahitya Kala Parishad Award RAMLILA AND KRISHNALILA Sushil da also became the backbone of Delhi's 'Indian Ballet' scene as a composer - a clear carry forward of the Almora spirit in the capital. He steered two major developments in 50's and 60's. In 1957, Baba was invited by Sumitra Charat Ram of Bharatiya Kala Kendra to choreograph a massive 'Ramlila' with a professional ballet troupe. Since this was to condense the entire narrative of Tulsidas's 'Ramcharitmanas' into a 3-hour spectacle, the task was pretty humungous, as the capital did not have the infrastructure or artistic pool to draw upon. It was conceived as a joint-production - between National Ballet Centre (NBC) and Bharatiya Kala Kendra - the former providing the artistic dimension, and the latter the finance. Artists were imported, and the capital saw a major influx of talents from other states for this venture. Since Sushil da was already part of NBC, he naturally became part of ballet 'Ramlila'. But problems appeared on how to interpret musically the intricate and rich poetry in Awadhi of 'Ramcharitmanas'. Baba then invited Jyotindra Moitra from Kolkata, a major voice of Bengal IPTA, to join him in this project. Fondly addressed as Batuk da, he was a poet and composer, and ran his own choir in Kolkata that sang patriotic songs. Given his intellectual depth of understanding texts and poetry, he made a remarkable intervention - he selected and converted 'chaupais' from Awadhi, and dramatized renderings based on 'ragas' and 'talas' of Hindustani music. This was unprecedented, as the 'chaupais' were generally rendered till then, in a kind of rote/drone like pattern, often heard on the 'ghats' in Varanasi.  The music pit of Ramlila at Talkatora Stadium, Delhi (1957) Sushil da then collaborated with Batuk da, to give the fillip on the orchestra front, through making notations, background score to songs, as well as providing the dramatic interludes to all the scenes with exceptional instrumentations. By this time Baba and Sushil da had close understanding of each other's mind, and the entire effort turned out to be a breakthrough. Ballet 'Ramlila' opened to sold-out audiences at Talkatora Stadium in September 1957. The Statesman gave a full-page review. In no small measure, the success was due to the lethal combination of Batuk da and Sushil da... See pic of the music pit at Talkatora Stadium in 1957- Batuk da in center, Sushil da in second row on the left, and a host of musicians who became key to every ballet music in Delhi for decades - Barun Dasgupta (tar-shehnai), Anant Lal (shehnai), Shelly Dutta (vocals), Dinesh Debnath (sitar), Nemai Ghosh (sarod), Shankar (jal-tarang), Gaurang Chaudhary (left but not in picture-percussion). This was what 'Indian Orchestra' was all about! The next phase was even more interesting. Bhagwandas Verma, another student of Dada from Almora, had played 'Rama' in the first 'Ramlila' in 1957, with Baba as 'Ravana' and my mother as the first 'Sita'. Sumitra ji's colleague at Bharatiya Kala Kendra, Kamla Narendra Lal fell out with her, and set up Natya Ballet Centre independently. Kamla ji requested Bhagwandas Verma to lead the new entity as the Director. Yet another ballet troupe came into being, and their first venture was to choreograph 'Krishnalila' at a big-scale. Bhagwandas ji, in turn, invited Sushil da to compose music for 'Krishnalila'. This again was a full version - more than two and half hours. Sushil da set up yet another orchestra unit, this time all on his own. As such, the credit for the original music for 'Krishnalila' entirely goes to Sushil da - a production that ran every year around Janmashtami for weeks, with full entourage of dancers, live orchestra and singers. But this trajectory of Krishnalila was also leading to subtle and far-reaching developments, which was to change the entire complexion of music industry by 70's in Delhi... Changes in technology and reverse influence of Mumbai's film industry started making inroads in the Delhi scene. Till then AIR, and for that matter every government and private setup in arts was dependent on imported equipment for recording and broadcasting, which was increasingly becoming obsolete. BHEL had started making bulky tape-recorders, almost half-ton steel ingots - playing half-inch analogue spool tapes. By late 60s some private studios started operating with tape-recorders made in Japan, making inroads in the city via Singapore. By 70s, T-Series had started its outfit in NOIDA, sucking in most of the musicians employed with government departments to play for their pirated versions of Bollywood songs, which soon flooded the markets. In particular, the pressure was building up in 60s on ballet groups, and their ability to sustain orchestras at a professional level. AIR, Song and Drama Division, Bharatiya Kala Kendra, Natya Ballet Centre and other entities could afford to sustain musicians, but by 70s this was becoming increasingly difficult. Working for private studios was becoming more profitable, given the burgeoning music industry with cassettes, LPs, record players and tape-recorders making inroads into every home. Musicians were losing patience for long rehearsals and capacity to 'read' notations. They preferred improvisational structure in studio situations, or to be able to deliver with oral instructions that could be memorized in a short span. Percussionists with capacity to play multiple drums and instruments had disappeared by 80s, barring a handful. And digital online recording was the death knell - the process of composing music was de-structured to such an extent, that musicians could appear in studio, one by one, at any given time of their choice, to deliver their part of re-construction! Natya Ballet Centre was the first one to switch over to recorded music for their Krishnalila in early 70s. They invited well know composer Anil Biswas from Mumbai film industry to record their Krishnalila. He built upon the foundation Sushil da had already laid for the score earlier, and added some of his own songs and orchestration, with a lead female singer from film industry. Bhagwandas ji had to import a spool tape-recorder for Natya Ballet Centre from Singapore to be able to deal with this change of method in conducting rehearsal and performance. In course of time, he also learnt the tricks of recording on analogue tapes and machines. In 1977, he was gracious enough to record Baba's masterpiece, ballet 'Wolf-Boy' in his house, on a Sony spool tape-recorder, with Sushil da as the composer!! BHOOMIKA YEARS Before I go further, I want to convey my profound gratefulness at this juncture to the Dasgupta family. Abhiram Dasgupta, son of Sushil da, few years back passed on to me Sushil da's workbooks, notations, poetry, photographs and writings for Indian Youth Choir - both in Bengali and English. On February 27, I got a package from Sanjay Dasgupta, Abani Da's son, of a precious bunch of notations for ballets and operas done by Sushil da for Bhoomika and other groups in Delhi. Before Covid pandemic, I was able to record amazing reminiscences of Shila Mukherjee (Shilu di), daughter of Abani da, of her amazing journey from being born in Almora, her growing up at Central Squad of IPTA in Mumbai, and the multi-faceted contributions of Abani da. She alas, passed on thereafter... I know I have my task cut out for research for years to come, and I am honored to have all these as part of Narendra Sharma Archive. Baba registered Bhoomika in 1972, and by 1974 Sushil da was back as music director of the dance company, which lasted their lifetimes. To return to 'Wolf Boy', recorded at Bhagwandas ji's house, one incident has to be highlighted. Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA) under Mohan Khokar had commissioned the choreography for Second All India Ballet Festival in 1977. Till then, Baba was still insisting on using Indian instruments for orchestration, but Sushil da was pestering him that he needed to respond to changes that were already transforming the music world. Sushil da insisted on including a musician who was the earliest to master a synthesizer in Delhi. I vividly remember the loud altercation between Baba and Sushil da of his reluctance to use synthetic sounds. Sushil da insisted on his prerogative as a composer, and that he was only using them as effects. The new sounds used for the opening scene of wolves' dance, became a breakthrough, and Baba reconciled to Sushil da's ways. After that there was no looking back, and the complexion of Bhoomika's sound-tracks changed thereafter.  Notes for ballet Wolf-Boy Since I was the main protagonist of this ballet, it will be interesting to see and analyze the notes Baba and me prepared jointly (see pic-found in Sushil da's cache) for 'Wolf-Boy'. But the second set of notes I will like to refer here is of ballet 'Antar Chaya', recorded in 1992. This production was significant, as this was a reflection of both, of their artistic experience and life journey - as choreographer and composer. Over decades, each knew their respective struggles, observations of political events, nationalist underpinnings, and individual responses as creative artists. This reflected in the narrative of 'Antar Chaya' and there are comprehensive notes on this production...  Notation for Antar Chaya  Notes on Antar Chaya by Baba See the pics of the choreographic notes by Baba, and notations by Sushil da as composer. This indicates the capacity of paperwork both did, and insights on how their minds worked. Three dancers of Bhoomika who were part of this process, Sangeeta Sharma, Santosh Nair and Naresh Kumar, are mentioned in the music notation. Sushil da spent days watching rehearsals and having discussions. What is significant is the transformation of the musical style of Sushil da. He knew the changed situation in studios - they had become expensive, not many musicians were there to 'read' his music, improvisational structure had become the norm, electronic music had already occupied the soundscape, and a balance had to be created between 'old world' ambiance and new technological possibilities. Sushil da's notations, this time, reflect more as suggestions for himself that was effectively used on studio floor as memory texts!  Creative team for Closing Ceremony, Festival of India, Moscow, 1988 Both were dealing with the changing contexts of their art form. They were doing massive projects together (see pic of creative team for Closing Ceremony of Festival of India, Moscow). And yet they would turn to intense and intimate stories in ballets they did together in later years. The core concept that ran through 'Antar Chaya' was the dramatic turn that had taken place with regard to ideas of 'violence/non-violence' in their lifetime... Their last collaboration in 2005 was a 'Homage' to Gandhi. THE LAST CHAPTER  Creative team for NBC for Ramlila (1957) Since Sushil da was like a family member (see pic from 1957 with NBC with me only few months old), he often stayed with us for months at end in 50s and 60s, at our small home in Modern School. I had the privilege of seeing him at work in my childhood, sitting on a harmonium for hours at end, composing and notating the melodies, marking the division of instruments, making notes on percussion effects, and so on. Since the xerox machine was still decades away in 60s, he would make multiple copies through writing with ball pen on layers of plain white sheets having carbon papers in-between. He would give precise instructions to one and all, of what he wanted to hear from the ensemble. He had a gregarious sense of humor, and his laughter would carry far. He used this quality with dexterity in studios, to extract the best from diverse talents. Sushil da, for some unknown reason, nicknamed me 'Gulla'. I consider him my guru in whatever music making I have done since 2001 when I formally started composing for my dances. I remember he would often ask me to sit by his side in Bhoomika's recordings, asking suggestions on what instruments to use in a particular dance sequence. He scolded me once in 1987, when I used an album of Meredith Monk, an American composer, for my first dance for Bhoomika. His grudge was simple - I should have taken permission from him before using the track, since he was the official music director. And I knew, he would have insisted on composing himself, and it was not possible at that time as Bhoomika did not have funds for a novice like me. He encouraged me to make interjections. By 1979, Bhoomika had a full-time group through a salary support grant from ministry of education. The very first set of dances Baba choreographed in collaboration with Sushil da is worth noting here. By this time, Bhoomika had acquired a spool-tape recorder - a second hand, quarter-track Akai M 10. And I spent days learning the tricks of analogue recording. Sushil da encouraged me to record music for him on that machine, with a cheap mixer and microphones bought from a friend. My first recordings were 'Hans Balaka', 'Aalingan', 'Conference '79' and 'Hajjam' - all done at our home in Modern School. I even learnt to splice tapes manually, and did the editing myself, before going over to Saraswati Studio in Daryaganj, to get a master copy done for performance. Sushil da approved all!  First performance of a new version of Hans-Balaka, Gandhi Memorial Hall, Delhi (1979) I may mention here two episodes from those recordings. The very first dance Baba mounted in 1979, on the freshly trained dancers, was 'Hans Balaka' - the dance he created at Almora in 1940. While Sushil da attended rehearsals, he gave me a breakdown on how many versions he had composed for the dance since he met Baba in 1946. For Bhoomika, he recounted that he was picking up threads from the original score - Jiten Gului, the original composer of the dance in Almora, had left behind a copy of the notation with him in Mumbai, and he was composing the new version based on the original melodies! That dance still stands with the dance company! The second incident was with the next dance that was made - 'Aalingan' - with idea of circle and curve as core to movement design. After months of rehearsals, of finding a new movement vocabulary, when this 10-minute dance was condensed, Baba and Sushil da sat to discuss the music. For some strange reason, I suggested that this dance should not have a percussion element at all. Sushil da said 'Done!' The score was composed without drums of any kind - perhaps the first one in Baba's repertoire! I saw Baba and Sushil da as a closely knit unit for decades. As soon as a theme would be decided, both would meet to discuss. They often had friendly fights but had a tenacity to work in harmony for artistic ends. They would often joke in their old age of who will go upwards first... Baba went first. On January 14, 2008, on the auspicious day of Makar Sankranti, he left for the higher abode. By that time Sushil da had shifted to Mumbai to live closer to Abani da's family. We called Annu di, his wife, to inform Baba's passing, and we were told that even Sushil da was hospitalized and was in coma. On March 6, 2008, Sushil da passed on to his higher abode, not knowing that his partner had preceded him on the onward journey... I am sure both must be partnering up there on what they spent their lifetime of earthly self... pretty much in the same way they collaborated in making yet another of Bhoomika's seminal ballet in 1985 - 'Antim Adhyaya' (The Last Chapter).  Bharat Sharma's career in dance spanning over five decades is marked by diversity of experiences as performer, choreographer, teacher, writer, composer, film-maker and arts administrator. He currently leads Bhoomika, New Delhi. Post your comments Please provide your name and email id along with your comment. All appropriate comments posted with name and email id in the blog will also be featured in the site. |