|

|

|

|

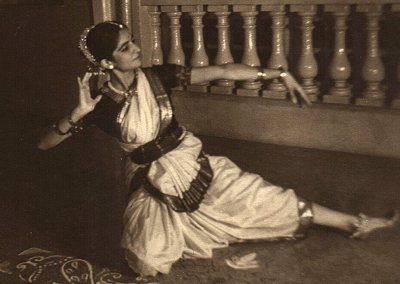

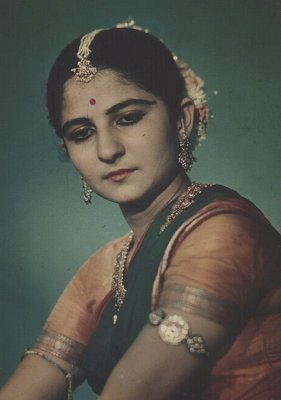

A tribute to Medha Yodh - a dance legend (1927-2007) - Ketu H Katrak, California e-mail: khkatrak@uci.edu Photos courtesy: Gaurang Yodh November 5, 2007 (A shorter version of this piece appeared in Sruti, October 2007)  "Bharatanatyam is a magnificent tool to center human beings, to give them an inner sense of being and to teach them focus, poise, discipline and the integration of different arts." - Medha Yodh, quoted in obituary by Lewis Segal (The Los Angeles Times, July 13, 2007, B9) Medha Yodh, a magnificent artist, teacher and performer of Bharatanatyam, and my guru of over twenty years passed away at age 79 in San Diego, California, at her daughter Kamal's home on July 11, 2007. Two daughters, Kamal and Neila, and two granddaughters survive Medha. I miss her presence, her passion for life, her warmth and caring, and her indomitable strength in facing life's challenges with wisdom, laughter, and a deep sense of bhakti. Medha was also my friend of over thirty years who saw me mature, not only in my study of dance, but from my early twenties (when I met Medha soon after I left my sheltered Zoroastrian home in Bombay for the US, to pursue higher studies in Literature) to my current fifties. As Medha met the great T Balasaraswati in Connecticut in 1962 and became her life-long disciple, so did I meet Medha not in Bombay but in Los Angeles in 1976 and became her disciple. Similar to Medha's great reverence and love for Balama is mine for Medha as my guru, as an artist of the highest caliber, and a remarkable human being. I heard about Medha as a teacher and performing artist from my friend Beheroze Shroff who met her at UCLA in 1976. Medha taught in the Dance Department there from 1976 on for 18 years. Characteristic of her open and lively spirit as a life-long learner, she showed up at Beheroze's Hindi language class. In this openness as in so much of Medha's aesthetic in dance and the arts, she was way ahead of her time.  Medha grew up in pre-Independence India, and left Bombay in 1947 for higher studies (MS in Chemistry) to Stanford University. Since she had not had the opportunity that my generation had had to study Hindi, she was eager to learn this language. She joined the class with UCLA undergraduates, some of whom were of Indian parentage, and the class blossomed into much more than the learning of Hindi into a community. With Medha's key participation, her unique ability to connect with young people and their concerns as Indian-Americans, Hindi lessons flowed easily into attending Satyajit Ray films showcased at the time at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as well as savoring Medha's incredible generosity in making delicious meals of curries, bataka shak, chappatis, puris, rice, dal, papads, achaar among other delicacies. I recall many evenings of food flavors and aromas blending beautifully with the night-blooming jasmine outside her kitchen door. After the meal, often Medha would revel in how "perfect" the curry had turned out that evening as we sat in the gathering twilight on the steps leading from her kitchen into the garden with a magnificent avocado tree, talking in our common mother-tongue of Gujarati about the day's events, about dance, about life in India and in the US. Such a flow of learning (Hindi or Bharatanatyam) with life, whether expressed via cooking, or helping someone, is a deeply cherished ideal that I have learnt from Medha. It is similar to how she explained the concept of bhakti to me - not only as a deeply personal religious feeling, but equally expressed in daily life as in the devotion that one imparts in teaching, or in listening to a friend in need, or in loving a child. Medha's values so resonated with my own growing up in a Zoroastrian household, and later, Medha's Zoroastrian community of friends in LA used to tease her that she must have had some connection with us in our past lives! When I first stamped the tei ya teis under her attentive eyes and listening to her voice keep the talam, the rhythms and the sounds resonated from somewhere in my subconscious. And I recalled waking up almost daily during my childhood to MS Subbulakshmi's voice thanks to my father's love for Carnatic music. Medha was remarkable in being receptive to other dance traditions, such as her taking classes in Balinese and Javanese dance when these styles were taught at UCLA. She was eager to learn the different ways in which the body can be trained. She was equally interested in modern dance and experimentation with music and advised many students during their Master of Fine Arts projects at UCLA who were interested often in creative choreography. Medha had the eye, intellect, and aesthetic to look at something and to see if it worked or not. She did not judge anything out of hand simply if it departed from tradition. She was a highly respected dance critic and served as judge for Dance Kaleidoscope showcase in California, where she was invited year after year to serve on a panel of judges.  Medha's life and dance have been an inspiration for me. She has taught me something as basic (though not simple) as standing up straight, becoming aware of how the study and practice of Bharatanatyam can be integrated into one's life. The value of bhakti, deep devotion that inheres in many traditional Bharatanatyam items, was something that Medha valued, though she never let it deteriorate into literal-minded religiosity. For her, bhakti was personal, a spiritual feeling that the dancer felt in her very body and that she conveyed to an audience. Medha was never prudish, but glamorously forthright in the depiction of the erotic in shringara, following in her guru Balasaraswati's legendary abhinaya. As with Bala, so with Medha - depiction of love for a deity was rendered as passionately as the love between of the nayika for her lord, or a mother for her child. I remember the thundering applause when Medha had the audience in UCLA's Schoenburg Hall raptly involved as she danced the varnam (and especially the quickening pace of charanam) Samike. I continued to study with Medha from 1976-1996, totally smitten by a profound love for Bharatanatyam and the rhythms and lyrics of Carnatic music. I would travel from my various job locations on the East coast (New Haven, Washington DC, Amherst, Massachusetts) to Medha's doorstep on 3833 Minerva Avenue in Los Angeles. Bharatanatyam sustained me and gave me a center, connecting me to home via my body, mind, and spirit. She taught me so much more than the adavus, and so much of the in-between nuances of padams and varnams. Medha's teaching was never rushed, moving from one item to another, collecting them in a kind of personal bank. This is a common tendency in our fast-paced lives; and when visiting artists come from India and teach local Indian-American students a certain number of items. Medha believed in the traditional methods of teaching that included rigorous training of the basics (I did adavus for more than a year); she never went ahead until a certain section was mastered. Medha was exemplary in practicing the old adage of teaching Bharatanatyam (as is true for any classical dance style) by taking the time that was needed, even savoring the nuances as they came up in the process of learning. She knew intuitively and as a gifted teacher that a certain amount of time is simply needed for the kind of knowledge and movement to sink into a student's mind and become part of her bones and muscles. What she taught, she practiced herself, so it was always a magnificent experience to see Medha dancing -the firm rhythmic foot patterns of the tat ti me tu in a charanam with the upper-body totally free and graceful in her soulful abhinaya. Medha was also a mother-figure, an elder whom I respected and loved deeply, someone with whom I could talk about anything: confusions of the heart (common in one's 20's and 30's), as well as my ups and downs in writing my doctoral dissertation in the late 1970's. At one very frustrated point in the writing, and having been totally captivated with the aesthetic of the music and movement of Bharatanatyam, I wanted to become a professional dancer. Medha, knowing the rigors of survival as a dancer said, wisely and firmly, "You can always dance. But, you must finish what you have started (my Ph.D)." Her wisdom was always matched with her deep warmth and caring. Among my most favorite memories of spending time with Medha were our attending many dance programs in the Los Angeles area and then discussing the many intricacies of what worked and what did not. I learnt so much from her aesthetic that demanded the highest standards and I learnt to appreciate the very best in performing artists. Medha would joke with me and say, "You are now brain-washed, kiddo!" I recall how excited we were when we saw Ramaa Bharadvaj's Panchatantra with the creative use of masks, innovative music and movement; or when we attended the dance programs of Viji Prakash with her then child Mythili (now in her 20s), blessed with incredible talent, grace, and energy. Medha was very supportive to this younger generation of dance teachers who came to the US much after she had in 1947 when the South Asian American community was not as visible as it became in the post-1970s. Medha and I have always been great fans of Mythili Prakash (Viji Prakash's daughter) as she has blossomed into a remarkable artist who performs today in different parts of the world. She also gave her sincere encouragement to other talented second-generation dancers such as Swetha Bharadvaj (Ramaa Bharadvaj's daughter), and in Kathak, Amrapalli Ambegaonkar (Anjani Ambegaonkar's daughter), among others. Medha earned the highest respect and love of many local Bharatanatyam dancers in Los Angeles such as Ramaa Bharadvaj, Viji Prakash, Anjani Ambegaonkar to name a few. She offered her keen and intelligent advice and feedback for their dance projects, and in fact, encouraged them for years to choreograph new work, with new music to depict the immigrant experience in the US. In an interview with me (in my article, "Body Boundarylands: Ethnicity in Bharatanatyam and in daily life") Medha asked, "Is there nothing worth creating in dance from (our) lives in the US?" She did not want dance teachers to simply recreate a monolithic, even a solely Hindu India for the diasporic community, and she certainly did not endorse the depiction of regressive aspects of Indian tradition. Medha rather saw ways of reinterpreting tradition from within, in the interpretation of padams, even in the celebration of femaleness and acknowledging the very power of the female in her shakti. What I love about Medha's aesthetic was its emphasis on the dancer's inner feelings and the goal of communicating them to an audience rather than emphasizing costume and aharya. I recall how she explained to me that the purpose of the jewelry and the mehndi (nowadays red magic markers!) on the hands and feet, bangles, earrings, the middle belt (to accentuate the shape of the dancer) created different geometric patterns in the designs of the many adavus and jatis - all this was for the purpose of an inner transformation. The dancer was no longer herself nor was she as in her everyday life. For that time on stage (as in the temple in prior times), she was the nayika, or the king, or the child, and she became these characters via the intense training in nrtta and abhinaya, in Carnatic music, in rhythm, in catching the nuances of the gamakas for her abhinaya. The dancer's goal is to transcend her physical self and to become the dance. I recall Medha always encouraging me to strive for this ideal, and I feel blessed to have seen Medha perform and to have felt the rasa that she conveyed via her creative and devotional energy. One of my favorite memories that give a glimpse into Medha's direct and loving personality was her remark, "Don't dance with your head!" Only Medha could see through my feet into my over-zealous and somewhat anxious brain that until a movement is mastered, experiences it as being "too fast" and somewhat "impossible." Not until the logic of the pattern, the correct positioning of the araimandi, the breathing are integrated into the body could I convey a sense of ease in dancing the most complicated jatis, tirmanans, or emotional layering in padams. The way that Medha would marvel and rhapsodize about seeing Balama's "Krishna ni begane baro" is how I revere and treasure my memories of seeing Medha as a playful Krishna, as a nayika disdainful of her lord, as a nayika in the heights of devotional ecstasy. Her dancing embodied a devotion to the art itself. I loved her emphasis on the last "ing" in the word "dancing." "Don't just dance, enjoy dancing," she would say, with her eyes riveted on my feet as I did dhit dhit teis in the opening tirmanam of my favorite piece, Ma Moha Lahiri, or learning to express the satiric grandeur of Indendu Vacchitira, or the lyrical beauty of Teruvil varano and the deeply emotional quality of Sakhiye. These are Medha's gifts to me, gifts that nurture my body, mind, and spirit. "I am pleased you are using the dance in your life - it retrieves one's lost center for just living." - Medha Yodh, personal correspondence to Katrak Ketu H Katrak is Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. She is the author of Politics of the Female Body: Postcolonial Women Writers of the Third World (Rutgers University Press, 2006), among other publications. |