|

|

|

|

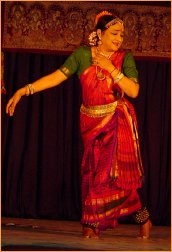

Tamil compositions for abhinaya - Lakshmi Viswanathan, Chennai e-mail: lakshminritya@hotmail.com (Courtesy Natya Kala Conference 2004) November 27, 2005  This is the year that Tamil has been officially recognized as a classical language. To commemorate this historic event, it is appropriate to focus on Tamil compositions in Abhinaya. There is no doubt in anybody's mind that the Padam is the best vehicle for realizing the best potential for rasabhinaya in dance. While other compositions may have crept into the vastly expanded dance repertoire, the essential musical and poetic beauty of a Padam is irreplaceable. Such a repertoire has almost been forgotten. But my demonstration based on my learning these songs from childhood will surely emphasize the importance of the great Tamil padam tradition. The Padam is an essential part of Bharatanatyam repertoire. It fulfils the scope of dance to evoke rasa, in a suitable and subtle manner. The music and poetry, which combine to make the Padam appropriate for Abhinaya (expressional dance), was understood by padam composers. It is widely believed by scholars that the source of such a composition can be traced to Jayadeva's 'Geeta Govinda.' Jayadeva is said to have lived nearly 500 years earlier to Kshetragna, the great padam composer. The Sanskrit verses of Jayadeva, extolling the amorous scenes between Radha and Krishna have stayed in the culture of the country to this day. It is therefore not surprising that Kshetragna, the 16th century Vaggeyakara, took to the Madhura Bhakti concept of love as expounded by Jayadeva and elaborated on the fine-tuned devotion towards Muvva Gopala. Kshetragna went one step further in giving vent to his imagination. He, the poet, becomes the Nayika or heroine to Krishna's (Muvva Gopala) Nayaka or hero. The romantic implications are a deep heart-felt attachment of the Nayika to the Nayaka. The step by step ascension of ideas inherent in human relationships towards the superior link with a divine personage - a god, a deity - is an integral part of this kind of poetry. It is this concept that eventually links the Bhakti culture as exemplified in the Viraha Bhakti poetry of Nammalvar, who is said to have lived in the 9th century, to all later Padams and Padam composers. A late evolution of Padams meant expressly for dance began only in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. If songs existed in Tamil meant for dance earlier to this, they are not available to us in their original. The Tanjore renaissance of Nayak times, made Telugu the court language and hence most of the compositions meant for dance were in Telugu. However, the Kuravanjis and later compositions give a new impetus to Tamil as suitable for dance. Padams are predominantly focused on Sringara rasa. Scholars have written extensive treatises on the role of rasa in dance and drama. Broadly speaking, rasa is a pleasing aesthetic experience, in which the rasika reaches a state of transcendental joy or fulfillment. This state is achieved by sublimating emotion. This liberated and universalized emotion draws the rasika to identify his own personal experience as a parallel reference point which does not hinder his relish of an artistic manifestation of feeling. Devoid of ego, he becomes a Sahridaya. The latent emotion which a rasika recognizes is known as Sthayi bhava. The Sthayi bhava of Sringara rasa is Rati or Love. There are many devises which contribute to the Sthayi bhava or Sringara. They are listed in Sanskrit texts as follows: Vibhava - determinants or 'alambana vibhava', such as the heroine, and the hero; and 'uddeepana vibhava' such as the time and place. Anubhava - consequents, which are manifestations of inner feelings. Satvika bhava - subtle manifestations of feelings, which arise from the innermost recesses of the psyche, such as trembling, horripilation, fainting, weeping, and other delicate changes. Vyabhichari bhava - transitory states, which further emphasize the emotional state of the character, like weakness, depression, joy, anxiety, distraction, indulgence, and so on, numbering thirty three, and more. Apart from the Natya Sastra itself, the most valuable definitions of these emotional states are provided by the 'Dasarupaka' of Dhananjaya. When a dancer judiciously employs the use of the varying shades of emotion as listed above, the Sthayi bhava is well defined, and the rasika is able to experience the essence of the particular rasa. In dance, the Padam affords ample scope for realizing the Sringara rasa to its fullest potential. It is widely understood that Padam composers knew without a doubt that the Sthayi bhava of Sringara is Rati, the erotic nature of love. While the shades of difference in Sringara hinge on three situations namely, 'Vipayoga' - separation from one's beloved, and 'Samboga' - union, which is blissful state of lovers enjoying togetherness. Poets have naturally seen and exploited the innumerable instances of intrigue in 'Vipralambha Sringara' to give vent to their imagination. The longings of the central character also suited the culture of Bhakti, which crystallized all emotion to one goal, which was the individual's fusion with the Eternal. In Padams, the dual approach which is made possible by the composition makes the dance vibrant with a variety of emotions and circumstances. On the one hand, the Nayika as the passionate woman pleading with her beloved to end the separation, addresses him directly or indirectly through her friend the Sakhi, making explicit and erotic references to the times she had spent with her beloved. On the other, she can also interpret this appeal in a spiritual vein as the yearning of the Jivatma for the Paramatma (the individual soul for the Supreme Soul). This apparent duality is a recognition that the greatest of man's passions carries him beyond all distinctions of physical and spiritual into the realm of supreme undifferentiated bliss. A sensitive and enlightened dancer draws upon the erotic and spiritual as two inseparable aspects of life. It is as true to her life as her audience's. From the point of view of Padams, the eight types of heroines who are identified according to their relationship with the hero have been like the guideline for dancers. However, it is obvious that Padam composers did not have these classifications in mind when they composed their songs. It is thus left to the dancers who have experience in abhinaya, and who are well acquainted with classical literature, to interpret the Nayika in the appropriate manner. Padams are believed to be the best illustrations of the integration of sound and meaning. The ragas used in Padams are carefully chosen to highlight the poetic content of the Sahitya. An extension of this is the actual prayoga of sangatis and gamakas to enhance the beauty of the lyrics. Creating a mood merely by the use of certain melodic phrases was well understood by Padam composers. The well known Tamil Padam composers are Subbaramayyar, Muthu Tandavar, Marimuthu Pillai, Papavinasa Mudaliar, and Patnam Subramanya Iyer. Others are Madhurakavi, Ghanam Krishna Iyer. Under a different yet important category come Gopalakrishna Bharati and Arunachala Kavirayar. Some may also add Oothukkadu Venkatasubba Iyer and Kavikunjara Bharati to this list. For a seasoned artiste, the wealth of Tamil literature provides many texts for Abhinayam. Pasurams, Tevarams, Virutthams and modern poetry such as Subramania Bharathiar's verses have all been used very effectively in Bharatanatyam. Lakshmi Viswanathan is a dancer/choreographer who presents the beauty of Bharatanatyam in its authentic form to audiences in India and abroad. She was the artistic director of the first Mamallapuram Dance Festival in 1991 and was twice elected as vice-president of the Music Academy. |